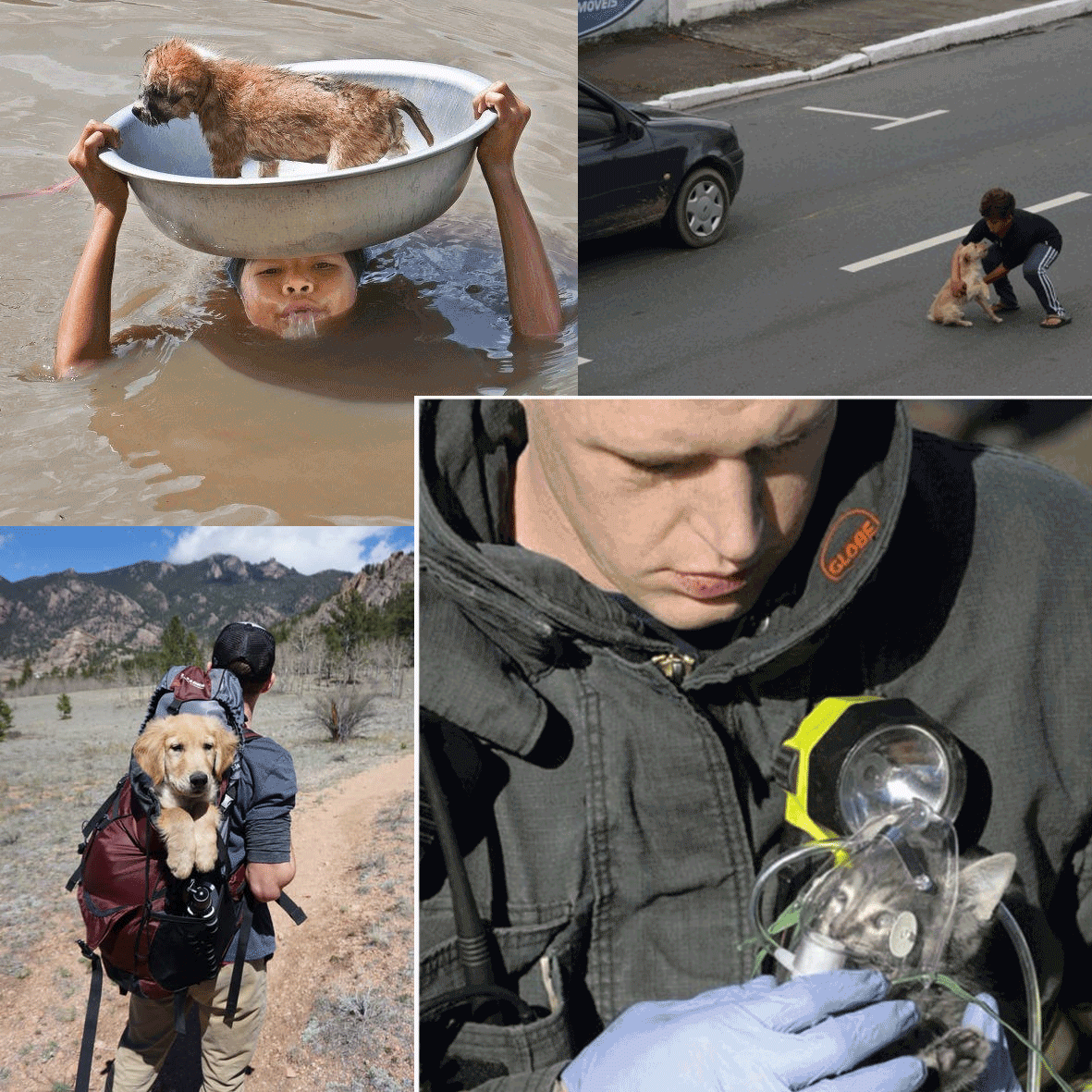

Can animals of different species create relationships and bonds similar to those they have with their own conspecifics? Let me tell you a story.

One winter morning, when I still lived up north, I looked out of the window and saw a white duck right in the middle of the yard. I almost missed it, so well his white plumage faded into the snowy environment.

Daniel, then a teenager, got very excited. “He’s freezing, Daddy, we have to help him,” he exclaimed.

We got warmly dressed, and even before considering eating breakfast, out we went to tend to this stranger in distress. Our presence didn’t frighten the duck, not even when we came closer. He didn’t show either any evident appreciation for the arrival of our rescue party. He must have been tired and freezing after having spent the whole night roaming around the frozen fields. We didn’t hold his lack of courtesy against him.

We found a wooden crate, duck-sized, grabbed some straw from the horse’s stall, and made him a comfortable refuge near the old water pump. He seemed to like it right away, went inside, tidied it up a bit and lay down like all ducks do with his beak on his back. We offered him food and water, which he didn’t touch and so we left him to recover.

“Fine, so now we can grab some breakfast, don’t you think?” I commented to Daniel.

The long and the short of it is that the duck stayed day after day, showing no intention of leaving. We gave him a name, Anders. I don’t know if he also gave us names. The other animals on the farm, horse, cat, dog, took it as it was. No one bothered him and didn’t show much interest either.

I thought he might die when I first saw him, so miserable he looked, but he was a tough duck. Not only did he survive, but he looked healthier and stronger for each day that passed. He also became increasingly assertive.

If we had any apprehensions about whether the other animals would give him a hard time, our doubts quickly dissipated. In fact, it was the other way around. Anders became the king of the farm. He ate everything—horse, cat, and dog food equally—and he took what he wanted when he fancied it. He would approach Katarina the cat, from behind, would peck at her tail, and, when she moved away, he would feast on cat food as he pleased.

Indy, the horse, didn’t escape his majesty’s moods either. King Anders would peck at Indy’s hooves until he moved away, giving up his horsey pellets for yet a ducky feast.

He would walk around tending to his businesses, whatever businesses ducks have, unconcernedly and much matter-of-factly. The only concern he showed were birds of prey. He would stand silent, looking up, holding his head sideways, one eye facing the sky until he rested assured that the bird wouldn’t dive on him.

It didn’t take long, though, before we all got accustomed to Anders and him to us. I can’t say that he ever bonded with anyone. He was his own. He wasn’t needy either. At the farm, we were supportive of one another when necessary, but we didn’t intrude on the others’ lives, and we weren’t over-protective either. Milou, the dog, would charge out of the door, furiously growling if she heard that Katarina was in trouble, which she was regularly. The neighborhood tomcats apparently found her too hot and worth risking a sortie into unknown territory.

Sometimes, at night, the fox would venture too close, and Katarina would be the first to detect her, creating some commotion. Anders would quack and shed feathers all the way up to his safe spot. Milou would charge forth fiercely once again as the defender of the kingdom, barking and growling, not knowing why, just in case. Indy, the horse, on the other hand, always kept his cool thru out all ordeals. Daniel and I would come last from our rooms on each end of the farmhouse, armed with our hockey sticks, more than once meeting one another in the yard, only wearing our boxers. I’m glad we lived out in the sticks where nobody could witness our antics!

We had a good life. We didn’t bother one another, shared the space and the resources we had, and we put up with one another’s’ peculiarities. That was what served us all best, I think we all agreed, but I can’t know what the others thought. We were a family, a herd, a clowder, a pack, and a brace.

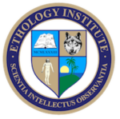

We belonged to different species, but for all intents, except reproduction, we functioned as any well-functioning group of animals of the same species. Thus, if you would ask me whether animals of different species can create relationships and bonds similar to those they have with their own conspecifics, I wouldn’t hesitate in answering yes (all going down to definitions). Did we have any hierarchy? Oh yes, you needed only to ask Anders, and it wasn’t in any way unsettling for any of us. It even felt natural and reassuring, I dare say. As long as we all knew what we were supposed to do and not to do, all was good.

I got the habit every morning, right after I got up, to look out of the window and be greeted by Anders. He would invariably stand there, in the middle of the yard, looking at my window always at the right time. It became a ritual, a reassuring one, I guess, for both of us.

One morning, Anders was nowhere. I knew right away what had happened. The fox had, at last, got the better of Anders, the king.

Featured image: If you would ask me whether animals of different species can create relationships and bonds similar to those they have with their own conspecifics, I wouldn’t hesitate in answering yes. Photo by Lifeonwhite.

Featured Course of the Week

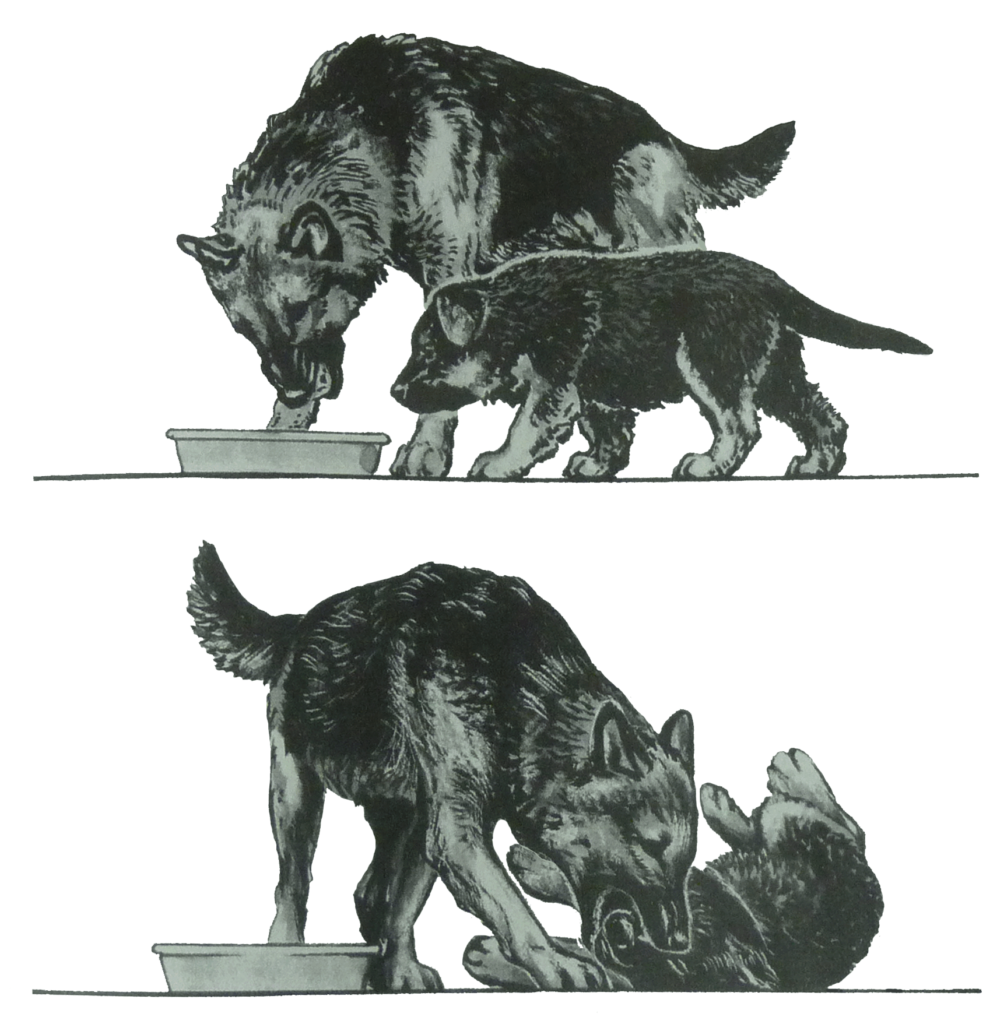

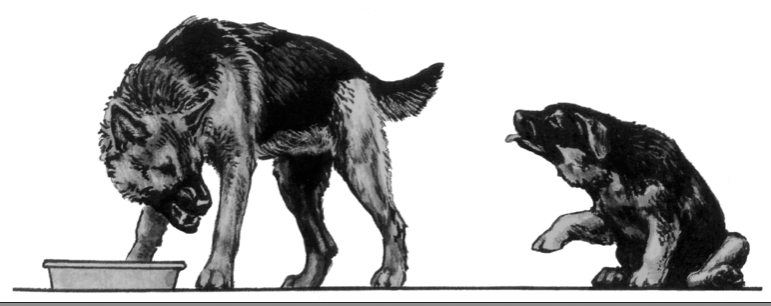

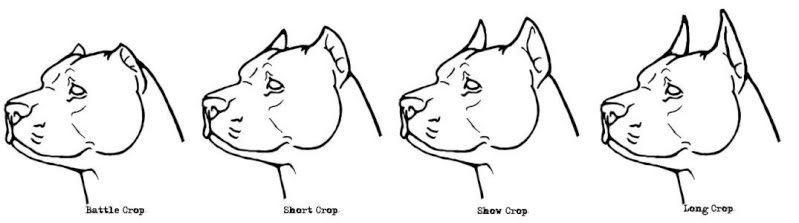

Agonistic Behavior Agonistic Behavior is all forms of aggression, threat, fear, pacifying behavior, fight or flight, arising from confrontations between individuals of the same species. This course gives you the scientific definitions and facts.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.