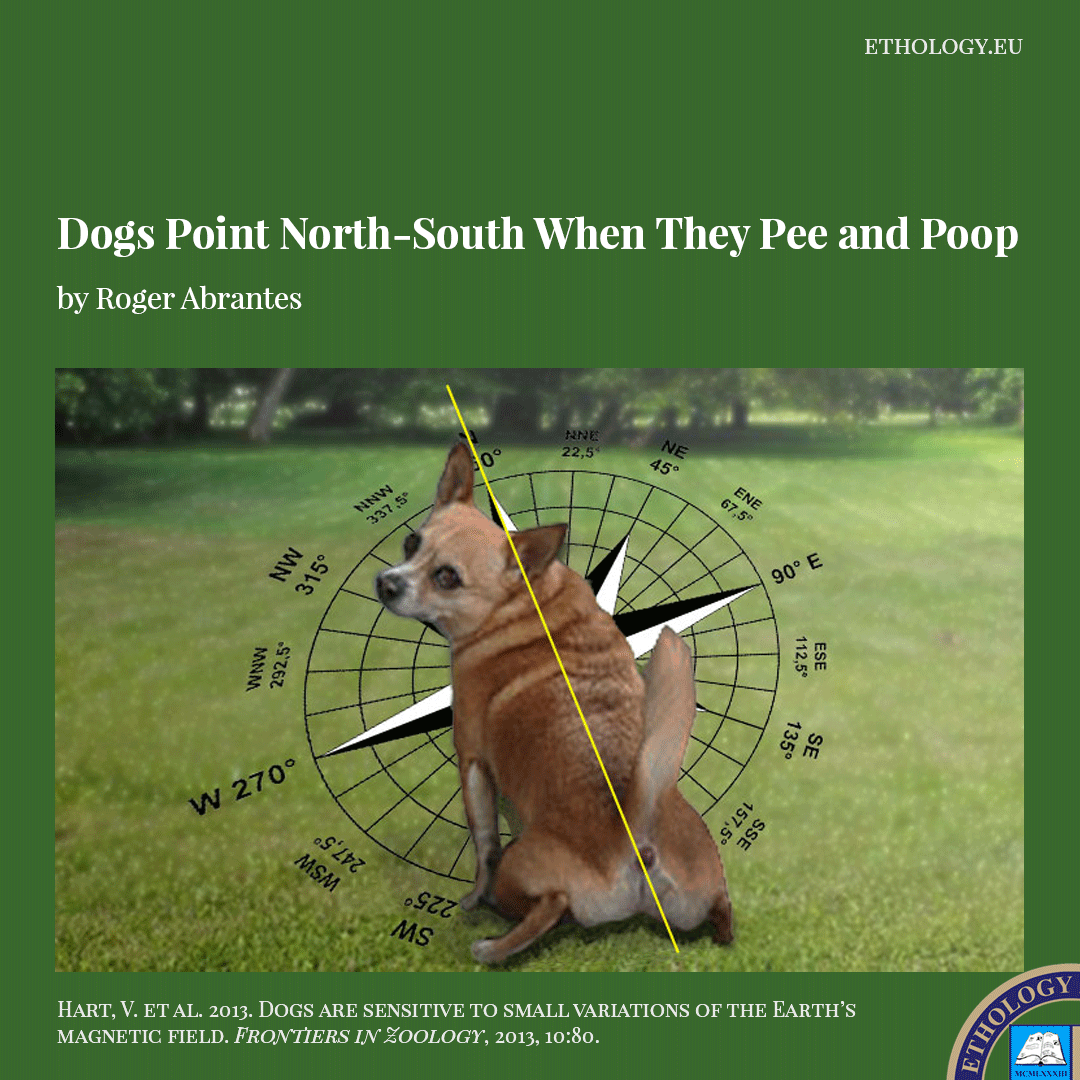

Dogs point North-South when they pee and poop. They use the Earth’s magnetic field when urinating and defecating, aligning their bodies in the N-S axis.

If I wrote this on April 1st, everyone would take that for an April Fool’s prank. It is not. It is the conclusion of a scientific project conducted by Hart et al. and involving researchers from the Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences, and the Faculty of Biology, University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany (Hart et al. 2013).

Dogs Register Small Variations in Earth’s Magnetic Field

The study concludes dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) register small variations in Earth’s magnetic field after examining the behavior of 70 individuals (28 males and 42 females) belonging to 37 breeds, collected by 37 dog owners/reporters.

The researchers collected data on alignment during defecation (n = 1,893 observations, 55 dogs) and urination (n = 5,582, 59 dogs) from December 2011 through July 2013 in the Czech Republic and in Germany.

Under calm magnetic field conditions, dogs preferred to defecate with their bodies aligned along the north-south axis, even when sometimes facing south. Dogs not only favored N-S but also avoid E-W.

The data shows that larger and faster changes in magnetic conditions result in a random distribution of body alignments, i.e., a lowering of the preferences and ceasing of the avoidances, which may result from the magnetic disturbance or the intentional shutdown of the magnetoreception mechanism.

To avert any bias, all dogs moved in a free-roaming environment, off-lead and not restricted by walls or roads that would influence their movements. The routes of walks changed to exclude or limit pseudo-replication caused by the dogs defecating and urinating in the same few places.

The researchers also excluded the sun, polarized light, and the wind as determining factors for the body alignment of the dogs.

No Differences Between Males and Females

The study found no differences in the alignment of males and females during defecation and of the latter during urination. They all assume similar postures during defecation and females’ urination. Urinating males showed slightly different preferences to the females’ choices. The male leg lifting posture, while urinating, could explain these discrepancies.

No Answer to Why Dogs Prefer the North-South Axis

We have no answer to why dogs prefer the north-south axis and avoid east-west. It may be intentional, in which case they must perceive the magnetic field with one of their senses (as a haptic stimulus), or maybe they feel more comfortable aligning them in a particular direction (controlled at the vegetative level).

New Perspectives

Earlier studies confirmed that the natural fluctuations of the Earth’s magnetic field may disturb orientation in birds, bees, whales, and even affect vegetative functions and behavior in humans.

Studies on the wolves’ (Canis lupus lupus) homing are inconclusive. We cannot rule out the possible influence of an inherent sense of direction. There may be critical periods during a wolf’s life during which specific elements of its environment may imprint on it. In a study, the simplest hypothesis that explained the movement of four wolves was responses to visual, olfactory, and auditory cues with the latter probably being the most important. The wolves seemed driven to return to familiar territory, using the strongest learned exogenous cues (Henshaw and Stephenson 1974). Magnetoreception could have been a homing aid.

The findings of Hart et al. open new perspectives on how organisms use magnetic fields for direction.

References

Begall, S., Malkemper, P., Burda, H. (2014) Magnetoreception in mammals. Advances in the Study of Behavior, 2014. pp 45-79.

Dimitrova, S., Stoilova, I., and Cholakov, I. (2004) Influence of local geomagnetic storms on arterial blood pressure. Bioelectromagnetics 2004, 25:408–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/bem.20009.

Hart V, Malkemper EP, Kušta T, Begall S, Nováková P, Hanzal V, Pleskač L, Ježek M, Policht R, Husinec V, Červený J, Burda H. (2013) Directional compass preference for landing in water birds. Frontiers Zool 2013, 10:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-10-38.

Hart, V. et al. (2013) Dogs are sensitive to small variations of the Earth’s magnetic field. Frontiers in Zoology 2013, 10:80.

Henshaw, R.E., and Stephenson, R.O. (1974) Homing in the gray wolf (Canis lupus). J Mammal 1974, 55:234–237.

Southern, W.E. (1978) Orientation Responses of Ring-Billed Gull Chicks: A Re-Evaluation. In Schmidt-Koenig K., Keeton W.T. (eds) Animal Migration, Navigation, and Homing. Proceedings in Life Sciences. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 311-317.

Featured illustration by Anton Antonsen.

Featured Course of the Week

The 20 Principles Animal training is a craft: half science and half art. This course and the included online book give you the 20 indispensable principles you must know to become a skilled animal trainer. It is the best crash course in animal training one can wish for.

Featured Price: € 148.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.