The first time I realized it for real was maybe 20 years ago. I was giving a horse workshop in LA, and they had gotten me a Mustang stallion to work with.

I looked at him for a moment as he looked at me. There was no defiance or diffidence in our gazes. We were just two lost creatures thrown in the arena of life. I cannot know what he thought at that moment. Maybe he was dreaming about running in the great plains of the mighty North-American continent where his ancestors once roamed freely. As to me, I found myself longing for home, for the comforting peace of my South-Andaman sea. None of us dared to move. The seminar attendees were absolutely silent, sensing or expecting they were going to get value for their money.

I might have been as reticent about the situation as the horse was. I don’t know who started it—maybe the horse, perhaps me, or both at the same time. As we began walking, suddenly, we were in sync. Slower, quicker, left, right, stop, we were mirroring one another: no words, no big gestures, just motion. We were not adversaries, not in opposition. We were partners at that moment. Our differences did not matter; our similarities did. We were like dancing together. If one of us missed a beat, the other would immediately step forward and follow up.

Many years later, in a completely different environment, I experienced the same again. I was diving in the magnificent South Andaman, so spellbound by the underwater beauty around me that I think I forgot I was just a human out of my natural environment. Without realizing it, at first, I found myself following the movements and the rhythm of a school of snappers swimming in front of me. Before I knew of it, there were another fish all around me, and they didn’t seem to be bothered at all by the presence of this bubble-making, definitely not a fish-like creature. For the first time underwater, I felt I was not a stranger, a visiting tourist.

Life has a rhythm, I learned. Since then, I’ve applied the rhythm factor to all my interactions with animals independently of species. When I train dogs, I always begin by getting acquainted with the dog, walking with the dog rhythmically forth and back. Once we have established contact, all the rest works much smoother, independently of what we’re supposed to do.

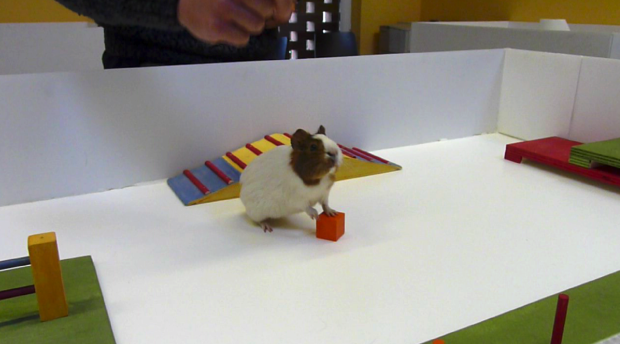

Yesterday, I showed it to my Guinea pig camp attendees. We worked on coordinating the movements of the team mates like a school of fish. I think it became clear, yesterday, what I meant days earlier when I emphasized how crucial it was for us to control ourselves, our movements and our emotions. Once they were all synced, the Guinea pigs fell in, and the results did not wait to show up.

Yesterday was the day we “waltzed with the Guinea pigs” at the rhythm of life.

Waltzing with the piggies at the rhythm of life. Victor Ros (Ethology Institute’s Graduate Trainer) working with Guinea pig in Pancalieri, Italy, in 2013. Being a skilled horseman, Victor knows the importance of rhythm (filmed by Roger Abrantes).