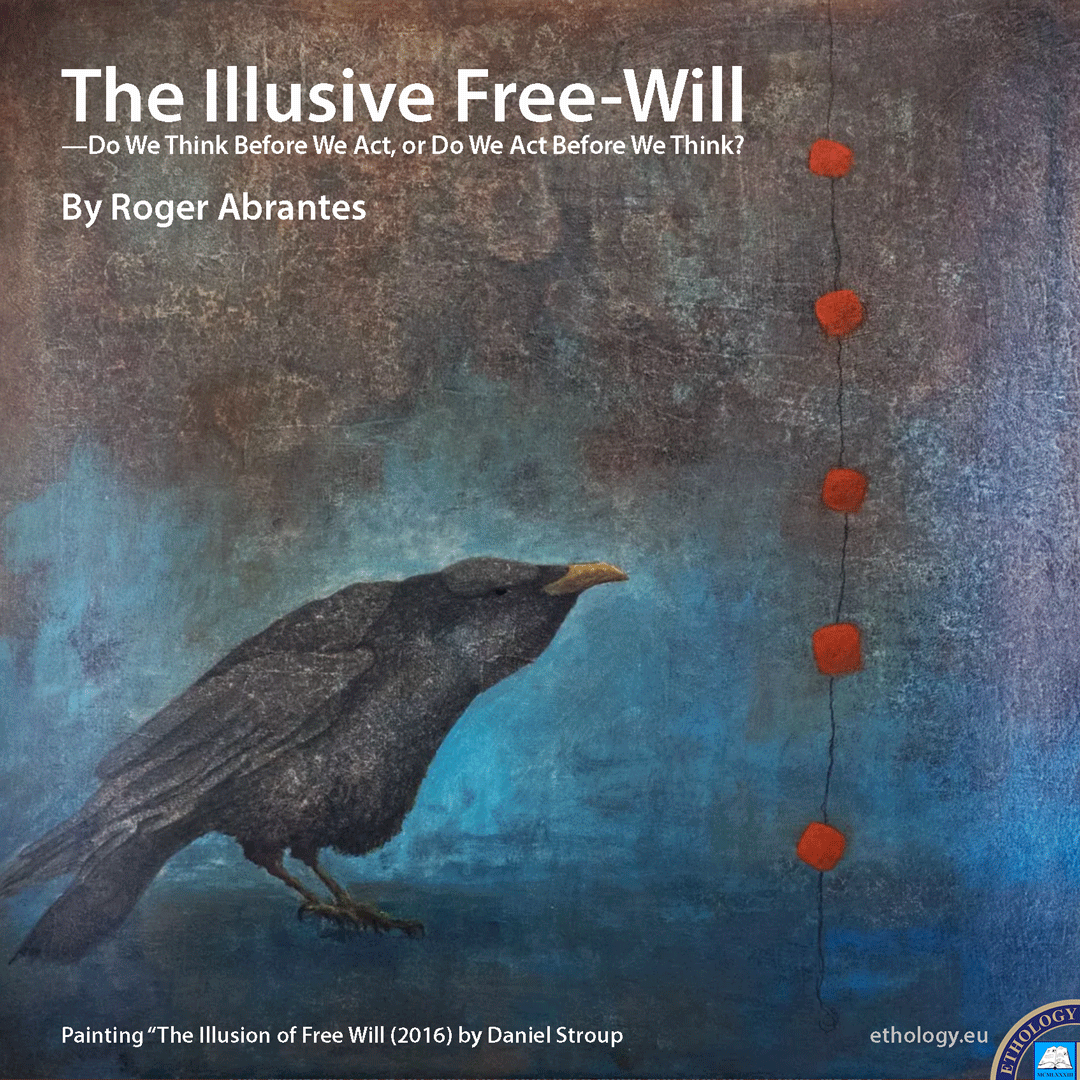

The Illusive Free Will

—Do We Think Before We Act, or Do We Act Before We Think?

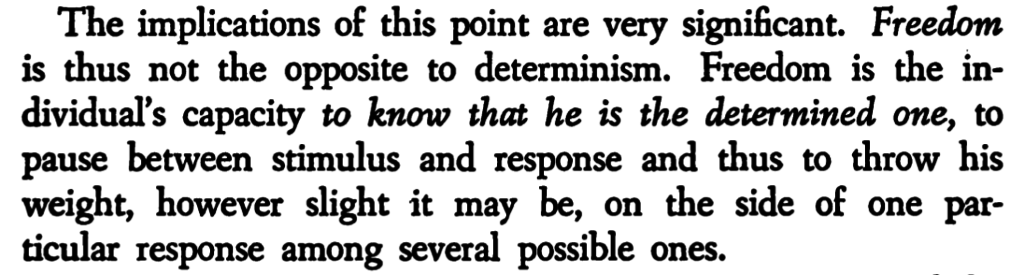

“Freedom is the individual’s capacity to know that he is the determined one, to pause between stimulus and response and thus to throw his weight, however slight it may be, on the side of one particular response among several possible ones.” This quote is from page 103 (of which I give you hereby a photo) of Lloyd-Jones, E., Westervelt, E. M. (1963) Behavioral science and guidance: proposals and perspectives. New York: Bureau of Publications, Teachers College, Columbia University.

We find this text frequently misattributed, misquoted, modified, and adulterated to suit various purposes and agendas on today’s overwhelming social media, where everybody knows everything—and nobody knows nothing (as they say).

Let’s take a breather for a moment, ponder, and analyze what’s behind the (original) quote without the social media’s razzle-dazzle.

There is a space—a tangible time gap—between the moment of an event and our reaction that we might use productively if we intentionally allow it to be there and engage it critically. That is, in other words, what the author means. It is an enticing proposition based on solid research from the previous decades.

The question of free will is a millennia-long one—in which neurophysiology only recently entered the fray. Theories of free-will focus on two fundamental questions: its possibility and nature. Some define free will as the capacity to make choices undetermined by past events. Determinism, on the other hand, sustains that only one sequence of events is possible and is inconsistent with free will. In contrast, compatibilism maintains that free will is consistent with determinism.

For over twenty years, experiments have suggested that, unbeknownst to us, a substantial part of mental processing occurs unconsciously, i.e., even before we know we plan to act. When we become aware of the brain’s actions, we ponder and mistakenly believe our intentions have caused them. “Your decisions are strongly prepared by brain activity. By the time consciousness kicks in, most of the work has already been done,” according to Haynes (2013).

Many processes in the brain occur automatically and without involving our consciousness. That is a defensive mechanism preventing our minds from being overloaded by basic routine chores.

We assume our conscious mind makes decisions. Our current findings question this. Researchers—using fMRI brain scans—could predict participants’ decisions up to seven seconds before the subjects had consciously made them.

If we decide before we are even aware of it, then the question is what mechanism decides for us. The prevailing view in neuroscience is that consciousness is an emergent neural phenomenon. The firing of the brain’s neurons results in consciousness and the sensation of free will or intentional action. These findings (Libet 1985) may not surprise neuroscientists who believe consciousness arises from brain activity (rather than brain activity originating from consciousness) since they view the conscious experience of free will as an emergent phenomenon of brain activity.

Researchers conclude that cerebral initiation of a spontaneous voluntary act begins unconsciously. However, within about 150 ms after the precise, conscious purpose emerges, we can still deliberately control the ultimate decision to act. Subjects can “veto” motor function for roughly 100–200 ms before a set time to act. That is the gap, the pause, so quoted and misquoted.

Whether that gap suffices to overcome the centuries-long free will quandary is highly arguable.

________________

References

- Dennett, DC (2003). Freedom Evolves. Viking Press.

- Fischer, JM & Ravizza, M (1998). Responsibility and Control: A Theory of Moral Responsibility. Cambridge University Press.

- Haynes, J-D (2013). World.Minds: Do We Have Free Will? (Charité Berlin).

- Libet, B (1985). Unconscious cerebral initiative and the role of conscious will involuntary action. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(4), 529-539. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00044903.

- Park, H-D et al. (2020). Breathing is coupled with voluntary action and the cortical readiness potential. Nature Communications, 2020; 11 (1) DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-13967-9.

- Pereboom, D (2001). Living Without Free Will. Cambridge University Press.

- Soon, C, Brass, M, Heinze, HJ, et al. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nat Neurosci 11, 543–545. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2112

- Soon, CS, He, AX, Bode, S, Haynes, J-D (2013). Decoding abstract intentions, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. March.

- Strawson, GJ (1994). The impossibility of moral responsibility. Philosophical Studies 75 (1-2):5-24.

Photo: Painting “The Illusion of Free Will (2016) by Daniel Stroup.

Featured Course of the Week

Animal Welfare Animal welfare is an objective science studying the needs of animals, an interaction between natural science, ethics, and law. This course is a must for everyone working with animals. Learn how to assess your pet's quality of life.

Featured Price: € 148.00 € 98.00

Ethology is the study of animal behavior in its natural environment. This online course, created by Ethologist Roger Abrantes, is unquestionably one of your curriculum’s most fundamental courses. Without reliable knowledge about animal behavior, we can’t expect to develop gratifying relationships with our pets or the animals under our care. Some of this course’s content is at an advanced level and requires increased dedication on your part. However, your expanded insight into the wondrous world of animal behavior will be a plentiful reward for your efforts.

The ethology online course comprises ten lessons, each with a quiz, and an ultimate test that awards you a diploma once completed. Included in the course is the beautiful flip-page book on which the course is based.