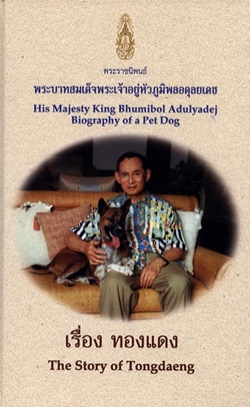

Tongdaeng, a previous Bangkok stray, adopted as a pup by Thailand’s King Bhumibol Adulyadej, caught the heart of the Thai people. The book on her life story, “The Story of Tongdaeng,” or เรื่อง ทองแดง, written by His Majesty, turned into a best-seller the moment it went on sale.

Thais love their king, and customers wrestled over the last few books on November 12, 2002, when the book was launched and 200,000 copies were sold. That doubled the first-day sales of the best-selling Harry Potter’s book.

Tongdaeng’s rise from outcast to palace favorite began in 1998 when she entered the Chitralada Palace in Bangkok. It was a present from a medical development centre, which looked after stray dogs and knew that the King loved dogs.

The King praises Tongdaeng as one of the best-mannered, considerate, and respectful dogs in the world and as an example to all Thais on how to behave—particularly politicians. The King’s loyal subjects have been buying the book to read about His Majesty’s views.

The book contains messages on morality and manners—much-appreciated considering the stories of corruption surrounding the country’s politicians. King Bhumibol, a constitutional monarch, enjoys immense respect from his people. He introduces Tongdaeng as “a common dog who is uncommon.”

When chasing other dogs around trees, the King writes, she insists that they always run clockwise. Many readers interpret this as a call for national unity.

Tongdaeng can also pick up and open coconuts at the King’s seaside palace on the Gulf of Thailand even though this can take a long time and result in torn gums—advice to be patient and endure pain in times of adversity.

The King writes, “Tongdaeng shows gratitude and respect—as opposed to people who, after becoming important, might treat with contempt someone of lower status to whom they should be thankful.”

Thais worship their king and have the highest respect for him. He never directly criticises public figures, though he occasionally issues reminders to Thailand’s political leaders about their loose moral standards. Thais remember too well how King Bhumibol ended several serious clashes, particularly the one in Bangkok in May 1992, when the army shot at demonstrators protesting a military takeover. Millions of TV viewers worldwide witnessed the army chief and a democracy campaigner, General Suchinda Kraprayoon and Chamlong Srimuang, prostrating themselves in front of His Majesty as he ordered them to stop the hostilities for the good of the nation.

The ultimate message of Tongdaeng, the crossbreed stray, is that, even though you may be born into poverty, you can rise to the top by means of your attitude and manners.