Critical Reasoning

The Ocean Accepts no Sham

“The ocean accepts no sham” is a maritime saying. The sea is shockingly honest and uncompromising. Excuses, rationalizing, compassion, self-pity, ignorance, political correctness, yapping, and baloney cannot get you out of trouble on the big blue.

In our wealthy and spoiled societies of today, we get away with shallowness, fanaticism, hooliganism and, not least, tremendous uncritical thinking. Not so at sea.

You can’t hide at sea. You’ll meet yourself whether you want it or not, the only viable strategy being honesty and integrity. It’s that simple!

From the sea, all you get is the truth, the only truth and nothing but the truth—independently of what that might be. You can change the name of the facts with which your sensitivities can’t deal, but a storm will still hit you with the same fierce force; and the mighty winds will still tear apart your sails—no matter what you call it. Politics, demagogy, propaganda, marketing, and hidden agendas leave the sea imperturbable. No wealth can buy it. It deals with the poor and the rich equally. No status will influence it. Kings and commoners receive equal treatment.

What you believe or don’t, be it gods or mermaids, has no effect. Knowledge does.

Your “likes” and “dislikes” mean nothing; taking as it is, does.

No spoiled children and cry-babies accepted either; toughen up is.

You don’t take care of your boat; she lets you down.

You don’t like punishment; think and don’t make mistakes.

You don’t read the winds, currents, and tides correctly; you pay for it.

You are reckless; you pay double.

You grow over-confident; you pay thrice.

You try to control the sea; you’re a fool.

It is as simple as that.

The sea shows us the essence of life, clear as crystal, as obviously as the blue sky lights up after the early-morning fog.

The sea ignores crying, moaning, nagging, whining, bitching, boasting, and con-artists equally. It demands honesty, adaptation, skill, patience, and humility, loads of it.

By the same token, once you realize in your mind and heart that you are but a little ripple in the immense ocean, just one amongst numerous, and act as such, the sea rewards you handsomely with a generous portion of tranquillity in your mind and contentment in your heart.

Then, and only then, will you be able to see the storm in the eye with no fears, to have the courage of facing yourself with no qualms; and to raise your head and smile to the thousands of stars far above and beyond.

And so, once more, I weigh anchor,

And to the sea, I fare.

“All I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume,

and the sea-gulls crying.”*

* John Masefield in “Sea Fever.”

Do Animals Have Feelings?

Do Animals Have Feelings? Attributing human characteristics to non-human animals is wrong — no doubt about that. Furthermore, it seems to me, that the opposite (of anthropomorphism) is as wrong, that is, to say that animals cannot be happy or sad because these are human emotions. It is true that we can’t prove whether an animal is happy or sad, but we can’t prove either that it can’t. As Carl Sagan wrote, “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” We know nothing about one or the other. All we can see is behavior, and the rest is guesswork.

The argument for anthropomorphism is valid enough: if I can’t prove (verify) something, I’d better disregard it (at least scientifically); and I can’t prove that my dog is happy, sad, or loves me.

Then again, we are not better off with our spouses, children, friends, not to speak of strangers. What do we know about their feelings and emotions? We can’t prove either that they are happy, sad, or love us. We presume it (and we are often wrong) because we compare their behavior with our own when we are in notably similar states of mind.

You may argue that there is a difference between comparing humans with one another, and humans with other animals. We, humans, are, after all, members of the same species. It appears to make sense to presume that if I am sad when I show a particular behavior, then you are also unhappy when you show similar behavior. You may have a point, even though not a very scientific one—and certainly not always. Cultural diversities play us, as you know, many tricks. Some expressions cover entirely different emotions in distinct cultures.

Featured Course of the Week

The 20 Principles Animal training is a craft: half science and half art. This course and the included online book give you the 20 indispensable principles you must know to become a skilled animal trainer. It is the best crash course in animal training one can wish for.

Featured Price: € 148.00 € 98.00

It appears that our attributing feelings to others, e.g., being happy or sad, is not very scientific. It is more a case of empathy, or being able to set ourselves in the place of the other individual. Researchers have uncovered that other primates besides humans, as well as other mammals, show empathy. Recent studies have found that honeybees are capable of indicating a kind of emotional response; and honey-bees, as invertebrates, account for about 95% of all species.

It seems the only reason for my inference that someone feels something particular is by resemblance. If so, I fail to see why we cannot accept that animals (at least some species) also can be happy, sad, etc. The inter-species comparison is a more distant one, but are we not, ultimately, sons and daughters of the same DNA?

If we can’t prove that everyone experiences emotions similarly enough to allow us to attribute them to a particular category, it seems to me to make no sense to accept a claim based on the fact that because humans know of love, happiness, and sadness, other animals (absolutely) don’t.

Again, “A difference of degree, not of kind,” as Charles Darwin wrote, appears to me to be a prudent and wise approach; and to reserve further judgment until we can prove it.

Therefore, if it is a sin to attribute human characteristics to other animals, it must also be a sin to say that because we do, they don’t, because we can, they can’t. The first is, as we know, called anthropomorphism; the second, I will coin anthropodimorphism.

So, if you ask me, “Can my dog be happy or sad?” I will ask you back, “Can you?” If you answer, “Yes, of course,” then I’ll say, “If that is the case, so can your dog (probably) albeit differently from you—a difference of degree, not of kind.”

Bottom-line: don’t assume others feel the same as you, not your fellow humans, not other animals. Don’t assume either that they don’t, because they might.

Life is a puzzle, enjoy it!

Featured image: Don’t assume others feel the same as you, not your fellow humans, not other animals. Don’t assume either they don’t, because they might.

Learn more in our course Ethology and Behaviorism. Based on Roger Abrantes’ book “Animal Training My Way—The Merging of Ethology and Behaviorism,” this online course explains and teaches you how to create a stable and balanced relationship with any animal. It analyses the way we interact with our animals, combines the best of ethology and behaviorism and comes up with an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach to animal training. A state-of-the-art online course in four lessons including videos, a beautiful flip-pages book, and quizzes.

The Magic Words ‘Yes’ and ‘No’

Yes and no are two short words and, yet, they convey the most important information many living beings receive. On one level, this information regulates their organic and cellular functions; on another, their behavior, and ultimately, their survival. If I say these words don’t require any explanation, everyone would probably agree—and yet we’d be wrong. Did you know that in some languages, yes and no, don’t exist?

In my book “Psychology Rather Than Power,” written in 1984, I define ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in dog training for the first time. ‘Yes’ means “continue what you’re doing now,” and ‘no’ means “stop what you’re doing now.” I explain how to teach our dogs these signals, and I emphasize that ‘no’ is not an inhibitor (earlier called a punisher) and that it should always be followed by a reinforcer as soon as the dog changes its behavior.

As the years passed, I reviewed, improved, and refined all definitions, especially how to teach dogs these signals. In 1994, I wrote the first draft of SMAF, which provided the opportunity to analyze signals and teaching methods (POA=plans of action) with increased precision. The definitions of ‘yes’ and ‘no’ remained the same. However, SMAF enabled us to distinguish clearly between the two entirely different ways dog owners and trainers used the sound ‘no.’ One was a signal, as I describe; the other was an inhibitor. The inhibitor ‘no’ was pronounced more harshly than the signal ‘no’ but was fundamentally the same sound. Transcribing it into SMAF, we did not doubt that they were two different stimuli. The signal is No(stop what you are doing right now),sound(no), and the inhibitor is [!+sound](no).

Using an inhibitor as a signal to encourage the dog to do something is never a good idea as an inhibitor’s function is to decrease the frequency, intensity, duration, or topography of a particular behavior. Conversely, a signal’s function is to produce a behavior that we increase in frequency, intensity, or duration by reinforcing. Therefore, to strengthen the effectiveness of No,sound (the signal), we had to explain to owners and trainers very carefully that they should never use ‘no’ as an inhibitor. Amazingly (or perhaps not), many dogs could distinguish between the two ‘no’s,’ but we didn’t want to risk them forming a respondent association between the sound ‘no’ and an aversive. We would use any other sound (word), e.g., ‘phooey’ (‘fy’ or ‘føj’ in the Scandinavian languages), as an inhibitor.

Why the word ‘no’?

The word ‘no’ seemed to me at the time the best option to convey, “stop what you are doing right now.” After all, implicitly or explicitly, this is the way most of us use the word (when we have it in our language, that is). Of course, some people cannot say ‘no’ tactfully, but some people having bad manners shouldn’t detract from the meaning or value of the word, per se.

All infants have an innate understanding of ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Their bodies function on ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Their survival depends on it (Photo by Mike Robinson).

The magic words ‘yes’ and ‘no‘

‘Yes’ and ‘no’ are two words used for expressing affirmatives and negatives. The words ‘yes’ and ‘no’ are difficult to classify under one of the eight conventional parts of speech. They are not interjections (they do not express emotion or calls for attention). Linguists, sometimes, classify them as sentence words or grammatical particles.

Modern English has two words for affirmatives and negatives, but early-English had four words: yes, yea, no, and nay.

If you’re a native English speaker, you know what yes and no mean, and you have no problem using these words, from a linguistic point of view. You might have a problem using the word no from a psychological point of view, but that’s an entirely different story.

If you are a native English speaker and have never ventured into learning other languages, you probably believe there is no problem in answering any question with yes or no. After all, most things either are or are not, are either true or false, right? I’m afraid I’m going to disappoint you by demonstrating that you are wrong.

Even though some languages have similar words for yes and no, we do not use them to answer questions. For example, in Portuguese, Finnish and Welsh, you rarely reply to a question with yes and no. Portuguese: “Estás bem?” (Are you OK?) “Estou” (I am). Finnish: “Onko sinulla nälkä?” (Are you hungry?) “On” (I am). Welsh: “Ydy Ffred yn dod?” (Is Ffred coming?) “Ydy” (He is coming).

In Scandinavian languages, French and German (amongst others), you answer questions with yes and no. However, you have two different ways of saying yes depending on whether the question is an affirmative response to a positively-phrased question or an affirmative response to a negatively-phrased question. In Danish and Swedish, you say (ja, jo, nej), in Norwegian (ja, jo, nei), in French (oui, si, non), and in German (ja, doch, nein).

So far so good, but if you venture into the Asian languages, it gets far more complicated. Some Asian languages don’t have words for yes and no. In Japanese, the words はい (hai) and いいえ (iie) do not imply yes and no, but agreement or disagreement with the statement of the question, i.e. “agree.” or “disagree.” はい can also mean “I understand what you’re saying.” The same in Thai: ใช่ (chai) and ไม่ใช่ (maichai) indicate “correct,” “not-correct.” In Thai, you can’t answer the question “คุณหิวข้าวไหม” (Are you hungry?) with “ใช่” (correct). It doesn’t make sense, for what is it that you are confirming to be correct? The right answers are “หิว” (hungry) or “ไม่หิว” (not hungry). In all Chinese dialects, yes-no questions assume the form “A or not-A” and you answer echoing one of the statements (A or not-A). In Mandarin, the closest equivalents to yes and no are 是 (shì) “be” and 不是 (búshì) “to not be.”

Latin has no single words for yes and no. The vocative case and adverbs do it, instead. The Romans used ita or ita vero (thus, indeed) for the affirmative, and for the negative, they used adverbs such as minime, (in the least degree). Another common way to answer questions in Latin was to repeat the verb like in Portuguese, Castellano and Catalan (e.g. est or non est). We can also use adverbs: ita (so), etiam (even so), sane quidem (indeed, indeed), certe (certainly), recte dicis (you say rightly) or nullo modo (by no means), minime (in the least degree), haud (not at all!), non quidem (indeed not).

In computer language, yes and no appear as a succession of “A or B” conditions. If condition A is true, then action X. A computer’s CPU only needs to recognize two states for us to instruct it to perform complicated operations: on or off, yes or no, one or zero.

The theories of quantum computation suggest that every physical object, even the universe, is, in some sense, a quantum computer. The cosmos itself appears to be composed of yes and no. Professor Seth Lloyd writes: “[…] everything in the universe is made of bits. Not chunks of stuff, but chunks of information—ones and zeros. […] Atoms and electrons are bits. Machine language is the laws of physics. The universe is a quantum computer.”

The way computers use yes and no is the closest to our customary use of these terms. ‘Yes’ means “continue what you are doing right now.” ‘No’ means “stop what you are doing right now.” That is the implied meaning of yes and no in the majority of the sentences. “Are you hungry?” The answer “yes” would result in you getting food and “no” in the opposite. “Shall I turn right? ” followed by a ‘yes’ would make me continue with what I intended to do and if followed by a ‘no,’ would make me stop doing it. A ‘yes’ in response to “Did you buy rice, today?” would prompt me to continue doing whatever I might be doing and a ‘no’ would lead me to interrupt my errand to go and buy some rice. There are many other examples, but in general yes prompts or encourages a continuation, and no does the opposite. There is nothing particularly positive or negative in either. Both are valuable bits of information that we can transform into behavior to our benefit. Both save energy, the most precious resource for all living organisms.

Two peculiar aspects of ‘yes’ and ‘no’

As we have seen, some languages don’t have words for ‘yes’ and ‘no.’ That is a cultural phenomenon. For example, in Japan and Thailand, it is bad manners to be direct. Japanese and Thai people consider ambiguity to be a beautiful aspect of their language. The objective in courtesy is to convey the true meaning between the lines. The way one delivers a message should be as unclear as possible, especially when criticizing someone or rejecting an invitation. This linguistic feature is probably related to the sense of self-respect and honor so pronounced in both cultures, i.e. one doesn’t want to hurt other people’s feelings or lose face.

For example, I can’t say to a Thai employee that arrives late to work, “Arriving late is not acceptable. Please, rectify this in the future.” If I do, I won’t have an employee coming to work at all the next day or maybe ever again. I’d have to say, “If we had employees that arrived late, we would have to ask them to come at the right time, don’t you think?” That would have the desired effect. If you invite a Japanese to an event that he or she is not the least interested in, they will answer “I want to come, but unfortunately, it is impossible on that day.” That would suffice for me to understand that they are not interested without making me lose face. Suggesting another day (and missing the point) is considered impolite.

Thais use ครับ (khrap, by men), ค่ะ (kha, by women) and the Japanese use はい (hai) to show that they are listening to you because it is impolite for them to let you talk for any length of time without their acknowledgment. However, it does not mean they agree with what you are saying, they will comply, or that they even understand you.

Regarding animal training, a signal is “everything that intentionally changes the behavior of the receiver.” A command is “a signal that intentionally changes the behavior of the receiver in a specific way with no variations or only minor variations.” The words ‘yes’ and ‘no’ are probably the closest we come to commands. ‘Yes’ means continue and ‘no’ means stop and, as to most behaviors, there are few possible variations in continuing or stopping, if any).

Is ‘no’ a bad word?

‘No’ is not a bad word. On the contrary, it is a very useful word. It conveys information in a precise and efficient way. To get ‘no’ as an answer is as important as getting a ‘yes.’ Both save us energy and lead us to our goal. Personally, I like the words yes and no equally, and I wished people would learn to use them properly and more often.

The other day, I went into a store at a busy hour, and I didn’t have the time or the patience to wait. I said to one employee: “Excuse me, I have a question that you can answer quickly with a yes or no. Do you have a Time Capsule 2TB?”

“I have one, but it’s reserved for a customer,” he answered.

“What does that mean? Is he coming to pick it up or not?” I asked again.

“Yes, he is.” He answered.

“Well, then that’s a no, right?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said.

Why couldn’t he just have said no the first time? It would have saved us all time: me, the other customers in the line, and not least himself.

Another example:

United Airlines desk at the gate boarding to ORD: I approach and ask: “Do you have an empty seat on this flight?”

The United operator answers me: “That depends on your ticket, sir.”

“No, it doesn’t,” I reply, “whether or not you have empty seats does not depend on my ticket, It depends on whether all the seats will have butts on or not.”

A colleague of hers smiles and checks it. “Sorry, sir, this flight is fully booked. I have one seat on the next flight, but… it’s business class.”

“No ‘but.’ You can put a comma or an ‘and’ in there,” I say. It blows my mind. A seat is a seat, and that’s what I requested. A seat is not less of a seat because it is a business class seat.

“Excuse me, sir?” she replies with a smile, plainly not understanding my comment based on linguistics/logic.

“Never mind. Here’s my frequent flyer card. I have an e-ticket for the 7.13 pm flight. Please, upgrade it with my miles. Thank you.” I say smilingly, in an attempt to reinforce her behavior for having been able to think clearly (yes/no) for two seconds and for checking the availability on the next flight.

“Yes, sir.” Finally a short and precise answer!

Why couldn’t they have answered first ‘no’ and then ‘yes’ until they got the next bit of information if I had any to give them? It would have saved me (and them) time and energy. If the lack of words for ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in Asian languages is frustrating for the Western communicator, the refusal to use them, or their incorrect usage in languages where they exist and are well defined, is exasperating.

Why don’t some people like the word ‘no’?

Cultural differences apart, some people don’t like the word ‘no’ for the same reason that some dogs don’t like it: they associate ‘no’ with aversives. Parents are just as bad as dog owners in distinguishing between signals and inhibitors, and they make identical mistakes, which will later create problems to their children.

Of course, parents have to yell ‘no’ if the toddler is about to stick his fingers in the wall outlet (plug socket). There’s nothing wrong with that. What is incorrect, and creates the aversive respondent association with ‘no’, is the constant repetition without a reinforcer when the behavior stops. The toddler only learns that, sometimes, parents go berserk, and she has no idea why or how to avoid it. The toddler becomes so sensitive to the word ‘no’ that later, like many others, he or she would rather live with regret than to risk hearing a ‘no.’ This conditioning can also happen subsequently, in adult life, to which abusive parents, enraged spouses, and tyrannical bosses all contribute.

An elementary mistake, committed by both parents and dog owners, adds to the aversive connotation of ‘no.’ If we have to use inhibitors, we should never (ever) inhibit the individual, only the behavior. Inhibiting the individual may create traumas, a lack of self-confidence, the feeling of rejection, etc. Inhibiting the individual rather than the behavior can even produce aggressive behavior instead of decreasing the expected behavior.

The reason some people don’t like ‘no’ has nothing to do with the word or the message conveyed, but with the aversives to which it was (respondently) conditioned. Changing that goes beyond the scope of biology, animal behavior, and linguistics, and pertains to the realm of psychology.

Still, there’s nothing wrong with the word ‘no’ and particularly not with the message it conveys. There is something wrong with abusive parents, enraged spouses, tyrannical bosses and ignorant people (all potentially abusive animal owners). To forbid the word ‘no’ or to replace it with another, e.g. ‘stop,’ does not resolve the problem. The only thing that does solve the problem is to educate people, to teach them to respect others independently of species, race, and sex.

English Springer Spaniel on the trail: ‘yes’ and ‘no’ are indispensable tools to direct the dog.

‘No’ in dog training

The signal ‘no’ is indispensable in dog training. I use it constantly when training detection dogs, rats, and Guinea pigs and the animals respond correctly with no emotional response at all. I give the signal ‘search’ using sound, the dog searches, I reinforce it. I give the dog the signal ‘no,’ the dog changes direction, I reinforce it. If the dog stops and looks at me, I give the signal ‘direction’ with a stretched arm toward the desired target, I give the signal ‘search’ employing sound, the dog searches and I reinforce it. If necessary, while the dog searches, I can signal ‘yes’ to encourage the dog to continue searching (‘yes’ functions here as a signal and a reinforcer, not an exception at all).

For those of you proficient in SMAF:

PRS1. {Search,sound => Dog searches => “!±sound”};

PRS2. {No,sound => Dog changes direction => “!±sound”};

ALT2. {No,sound => Dog stops and looks at me => Direction,arm + Search,sound => Dog searches => “!±sound”};

If necessary:

PRS1. {Search,sound => Dog searches => “!±sound” => Dog searches => Yes,sound}; /* Yes,sound also functioning as “!±sound */

In languages where there are no words for ‘yes’ and ‘no,’ such as Thai, I use ใช่ (chai=correct) and หยุด (yut=stop) respectively for “continue what you are doing right now” and “stop what you are doing right now.” I don’t use ไม่ใช่ (maichai=not correct) because the sound is too close to ใช่ (chai=correct).

Some trainers don’t allow their dog owners to say ‘no’ at all in their classes. That is an option, particularly if we have a class full of badly-mannered dog owners, but if our class consists of average, well-mannered owners, I cannot see any reason to do so. If they are not well-mannered, maybe they should learn to be so before beginning training their dogs; and perhaps, by training them to be polite to their dogs, we could even make a change for the better in their lives in general by teaching them good manners toward their fellow humans as well.

Forbidding the signal ‘no’ in dog training is a grave mistake (and misunderstanding) in my opinion. Firstly, it is one of the two most critical signals in life. Secondly, we all need a quick, efficient signal to stop a behavior which might be fatal for someone we care about (human or animal). Thirdly, it would be an untenable waste of time and energy if we had to resort to diverting maneuvers every time someone (our dogs included) did something undesirable.

Substituting the signal ‘no’ with other sounds (words) such as ‘stop,’ or ‘off’ doesn’t solve the problem. It only transfers the conditioning to those new words. The problem is that some people just can’t speak nicely to anyone. Most dog owners yell their dog’s name, and they yell ‘come.’ What are we going to do about that? Forbid them to use their dog’s name and the word ‘come’? What’s the next thing we are going to forbid them? Rather than banning words, it seems to me a much better option to teach them to communicate properly. We need to explain to them that the words they use, the way they use them, are not signals but inhibitors and, by definition, they will not achieve the desired result. Quite the contrary, they will get an undesired outcome. We need to show them how appropriate signals produce appropriate behaviors.

Bottom-line: The fact that some languages don’t have words for ‘yes’ and ‘no’ and that Latin uses quantifiers instead, suggests there are cognitive as well as emotional elements connected to the meaning of both words. Maybe the logical human brain likes the precision and simplicity implied in ‘yes’ and ‘no,’ but the emotional human brain doesn’t. The universe and computers have no issues with ‘yes’ and ‘no’ perhaps because they are not emotional. Maybe ‘yes’ and ‘no’ appeared in some languages at a stage when action became more decisive than emotion. We don’t know. I haven’t been able to clarify any of these questions. Nevertheless, ‘yes’ and ‘no’ convey important bits of information in a succinct and precise way. In the languages, which contain them, we can use them correctly for our benefit.

Enjoy and don’t feel guilty because you are well-mannered and know how to say no.

References

- Abrantes, R. (2011). Mission SMAF—Bringing Scientific Precision into Animal Training.

- Abrantes, R. (2011). Signal and Cue—What is the Difference?

- Abrantes R. (2011). Commands or Signals, Corrections or Punishers, Praise or Reinforcers.

- Abrantes, R. (2011). Unveiling the Myth of Reinforcers and Punishers.

- Bloomfield, L. and Hockett, C. F. (1984). Language. University of Chicago Press.

- Boyd, K. M. and Osborn K. (1997). The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Parenting a Preschooler and Toddler, Too.

- Lloyd, S. (2006). Programming the Universe: A Quantum Computer Scientist Takes On the Cosmos. Alfred A. Knopf Publishers.

- Mueller, S. (2011) Learn to say “No.

- Powell, C. S. (2006). Welcome to the Machine. The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- Seife, C. (2006). Decoding the Universe. Viking Books.

- Sichel, M. and Cervini, A. L.A. Boundary is NOT a Rejection.

- Sonnenschein, E. A. (2008). Sentence words. A New English Grammar Based on the Recommendations of the Joint Committee on Grammatical Terminology. Read Books.

- Watts, R. J. (1986). Generated or degenerate? In Dieter Kastovsky, A. J. Szwedek, Barbara Płoczińska, and Jacek Fisiak.Linguistics Across Historical and Geographical Boundaries. Walter de Gruyter.

- Visual Thesaurus

- Wikipedia. Yes and No.

- Williams, C. P. and Clearwater, S. H. (1999). Ultimate Zero and One: Computing at the Quantum Frontier. Kindle eBook.

Featured image: ‘Yes” and ‘no’ are the two single most important signals in the universe. Photo: Atlantic puffins, Vesterålen, by Billy Idle.

Featured Course of the Week

The 20 Principles Animal training is a craft: half science and half art. This course and the included online book give you the 20 indispensable principles you must know to become a skilled animal trainer. It is the best crash course in animal training one can wish for.

Featured Price: € 148.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology and Behaviorism. Based on Roger Abrantes’ book “Animal Training My Way—The Merging of Ethology and Behaviorism,” this online course explains and teaches you how to create a stable and balanced relationship with any animal. It analyses the way we interact with our animals, combines the best of ethology and behaviorism and comes up with an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach to animal training. A state-of-the-art online course in four lessons including videos, a beautiful flip-pages book, and quizzes.

Critical Reasoning—on Aggression and Dominance

In the following, I will give you four definitions of aggression and dominance; and will analyze them determining whether and why they are good or bad definitions.

A Question of Definition and Convention

Behavior is tricky to study because it is highly dynamic depending on many variables. It is even more difficult to describe because nothing, or very little, is as clear cut as we would wish and our brains strive after. The difference between any two behaviors is like the difference between any two colors in the light spectrum. When is red not red but yellow is as tricky to assert as when friendly behavior turns into pacifying, pacifying into submissive, or submissive into fearful. It is, ultimately, a question of definition and convention.

Accuracy, Consistency, and Modesty

Behavior and emotion are intimately connected, and yet we can only see the former and guess about the latter. Generalizations are troublesome and prone to error. These inherent difficulties combined with poor definitions and sloppy use of the terms can only turn a difficult subject-matter into a nearly impossible one. My suggestion to attempt to remedy this is to formulate accurate definitions, to apply terms consistently, and to be modest in our claims and generalizations, leaving plenty of room for alternative hypothesis and improvement.

I will exemplify the problem with some representative statements about dominance and aggression, which I picked from articles on the Internet. The name of their authors is irrelevant in this context because my purpose is not to criticize single persons, only to point out fundamental errors and to help my readers to analyze what they read, to find their bearings, and develop their own educated opinions.

In all fairness, we must appreciate the problem any author faces when attempting to describe an everyday occurrence, like behavior, accurately while living up to a scientific standard; which we frequently register, and convey in daily language. It’s much more difficult than to write a mathematical sentence. “Between a rock and a hard place,” the author tries not to use too many technical terms, which require definitions on their own, putting him or herself at the mercy of everyday language and colloquialisms bound to a myriad of interpretations and misinterpretations. If you’re the author of one of the analyzed statements below, please regard my analysis as an aid. I’m definitely on your side, fully appreciating the burden of the task you so bravely undertook: to define and to explain.

Believe or not, the higher ranking (ethology term) or most distinguished (in human terms) dog is the one on the right. That is the function (and the beauty) of the evolutionarily stable strategy dominant/submissive behavior (when defined correctly). It resolves a confrontation without injury to either party, spending only a manageable amount of energy. The dog on the left shows pacifying behavior, which is a voluntary display of a mild form of submissive behavior. It’s politeness, recognition, in human terms (photo by unknown).

Example 1—A Poor Definition

Example 1: “In animal behavior, dominance is defined as a relationship between individuals that is established through force, aggression and submission in order to establish priority access to all desired resources (food, the opposite sex, preferred resting spots, etc.). A relationship is not established until one animal consistently defers to another.”

The author states that dominance is one kind of relationship: (“dominance (…) is a relationship”) with the function to “(in order to) establish priority access to all desired resources.”

The statement does not tell us explicitly what dominant behavior is, but leaves us guessing that since dominance “is established through force, aggression and submission,” it must be related to these behaviors; but it does not define aggression and submission, which are technical terms.

The statement seems either biased or too restrictive. One individual can establish a dominant (priority access, according to the author) relationship with another through motivation, persuasion, argumentation, bluffing, bribing, all without the use of force or aggression (aggressive behavior), independently of how we understand these terms.

Most social parents establish their dominance status over their offspring not by using aggressive behavior, but because they are better (older, more experienced) at solving problems (this is persuasion and argumentation) or only a limited and inhibited amount of force, which is quantitatively and functionally so different from aggressive behavior, that it deserves a new name (dominant behavior).

In some cases and for many reasons, most commonly age and experience, it is even the lower ranking (in need of protection) that bestows a higher ranking to the other (it is a “you decide”). Aggressive behavior and dominant behavior are, thus, not the same.

A hierarchy maintained employing aggressive behavior tends to be unstable, either because some of the lower-ranking leave the group (estimating that the costs of group membership out-value its benefits), or because they repeatedly challenge the higher ranking. Any hierarchy maintained by dominant behavior tends to be more stable because the lower-ranking individuals have greater benefits at relatively low costs.

The sentence “to all desired resources,” is too daring. We would not dare to say ‘all’ and we doubt very much that any individual ever controls ‘all’ desired resources (depending on the number, of course, but ‘all’ suggests many). No hierarchy is ever more consistent than it is regularly subject to changes. Even in established hierarchies, the highest ranking individuals do not always gain access to particular resources on particular encounters. Persistent dominant behavior from one individual toward the same other individual tends to turn their relationship hierarchical, but regular displays of dominant behavior must maintain it.

The sentence is not a definition of dominant behavior because to be so we would have to substitute dominance with dominant behavior and aggression with aggressive behavior, and we would get “dominant behavior is established through aggressive behavior,” which does not explain anything.

If dominance and aggression are the same, there is no need to call it something else: aggression would do. The term submission seems misplaced: “dominance is established through submission” is a contradiction since one is the antonym of the other. The sentence does not seem to make sense once we begin analyzing it, but we have a hunch of what the problem is: the author is confounding hierarchy with dominance. If we substitute one term by the other, then the sentence makes sense—a relationship can be hierarchical—though, it is still wrong because a hierarchical relationship does not necessarily involve force and aggressive behavior; it can include many other aspects, as we saw.

The sentence “A relationship is not established until one animal consistently defers to another,” is misleading. It gives the impression that no relationship at all exists between two individuals unless one consistently defers to the other, which is not true. There are many examples of relationships (most, as a matter of fact), be it between humans, wolves or dogs, where one of the parties does not consistently defer to the other. Quite the contrary, in most stable relationships, both parties consistently defer to one another.

In the statement above, and in general, we confound dominance with dominant behavior; we confuse a defining characteristic with an attribute.

A dog is not dominant as it is black or short-legged. A dog shows dominant behavior toward (condition 1) when (condition 2).

“A knife is a cutting tool” indicates a defining characteristic (permanent). “This knife is sharp” indicates an attribute (temporary). The correct is: “This knife is sharp to cut meat (=condition 1) today (=condition 2).”

Likewise, “Bongo is dominant toward Rover (=condition 1) when they find a bone (=condition 2).” More correctly, we should write, “Bongo showed today dominant behavior toward Rover when they found a bone.” We can also say, if it is the case, “Bongo shows, more often than not, dominant behavior toward Rover when they find an edible item.”

That is characterizing the behavior, not the individual. What we cannot say is “Bongo is dominant, Rover is submissive” because these are not defining characteristics of an individual.” These are attributes of their behavior under certain conditions even when these conditions seem to be rather encompassing.

Bottom line: The statement is not good because: (1) it defies observational data (aggression is not a necessary condition in a dominance relationship). (2) if aggression is a necessary condition, then we do not need to call it dominance, we can directly call it ‘an aggressive relationship’ (or antagonistic if you prefer a nicer name). (3) it is too restrictive (‘all desired resources,’ ‘a relationship is not established,’ ‘consistently defers’).

Example 2—A Circular Definition

Let us consider another example of a representative sentence, this time about aggression, taken from another article on the Internet.

Example 2: “So what causes aggression? Aggression is a response to something/someone the animal perceives as a threat. Aggression is used to protect the animal through the use of aggressive displays (growling, barking, tooth displays, etc.) or protect the animal through aggressive acts (biting). Aggressive behavior is most frequently caused by fear.”

We miss the definition of “threat” to be able to analyze the sentence conclusively, but assuming that threat means “an intention of imminent harm, danger, or pain” (The Free Dictionary), the statement is false.

A threat is only a threat if it threatens, that is if it succeeds in eliciting fear behavior (apprehended as imminent danger). Otherwise, if the threatened individual does not consider itself under imminent harm, danger or pain, then it is not a threat, it is just an exclamation (information).

Animals respond to threats (not exclamations), which are aggressive behaviors, by either neutralizing the opponent’s aggressive behavior (pacifying behavior), giving up (displaying active or passive submissive behavior) or fleeing (the most effective energy-saving measure when seriously threatened). When threatened, attacking would be the worst possible strategy. If attacking solves the problem, then the threat was not a threat at all (by definition) because it was not dangerous enough to qualify as such.

The only occasion when some animals respond aggressively to threats (not all, some freeze and die) is when pacifying behavior, submissive behavior, and fleeing does not have the desired effect of neutralizing the threatening (aggressive) behavior of an opponent. These are exceptional exceptions.

The sentence “Aggression is used to protect the animal through the use of aggressive displays (…)” is circular. Aggression being synonymous with aggressive behavior and display and act with behavior means that the sentence reads, “Aggressive behavior is used to protect the animal through the use of aggressive behavior or protect the animal through aggressive behavior.”

Furthermore, since the author writes in the passive, it leaves us with the feeling that aggression is some mysterious quality. Who uses it? Where does it come from? Re-writing it in the active, we get the even more nonsensical “The animal uses aggressive behavior to protect itself through the use of aggressive behavior or protect itself through aggressive behavior.” That is not exactly a statement likely to enlighten anyone, quite the opposite.

The sentence “Aggressive behavior is most frequently caused by fear” is the result of our use of terms without having given enough thought to their proper definitions. Fear does not elicit aggressive behavior. It would have been a lethal strategy that natural selection would have eradicated swiftly and once and for all. A cornered animal does not show aggressive behavior because it is fearful. It does so because its natural responses to a fear-eliciting stimulus (pacifying, submission, flight) don’t work.

Example 3—A Better Definition

Let us find out why a third statement, which we also took from the Internet, is much better than the two that we have analyzed above.

Example 3: “Dominance is not a personality trait but a description of a relationship between two or more animals and is related to which animal has access to valued resources such as food, mates, etc.” We can easily improve this statement by avoiding the unclear “is related to” and the passive construction of the sentence: “Dominance is not a personality trait but a description of a relationship between two or more animals; in a dominance relationship, the dominant animal has access to valued resources such as food and mates.” (We also drop the vague and unnecessary “etc.”).

This statement is not as restrictive as the first one we analyzed. For example, it does not claim aggressive behavior as a necessary condition. It allows for more options. It also says what the defined term is not (“not a personality trait”).

Good and Tentative Definitions

The art of making a good definition is to find the right balance between too much and too little and to state only the necessary conditions. A too restrictive definition has fewer chances to be adopted than a broader one, and a too broad definition risks losing its defining function. This definition of dominance is more likely to be accepted and adopted by a more significant number of people than the first one.

A proper definition defines precisely what it is supposed to define, and nothing else. A good definition gives an if-and-only-if condition for when an object or a term satisfies the definition. It is conclusive and exclusive. A good definition should also involve simpler terms than what we are defining.

Sometimes, we are compelled to use working definitions. A working definition is a definition we choose for an occasion and may not fully conform to the final definition. It is a definition at a stage of being developed—a tentative definition that in due time may turn into an established definition.

Example 4—A Good Definition

Example 4: “Dominant behavior is quantitative and quantifiable behavior displayed by an individual with the function of gaining or maintaining temporary access to a particular resource on a particular occasion, versus a particular opponent, without either party incurring injury. If any of the parties incur injury, then the behavior is aggressive and not dominant. Its quantitative characteristics range from slightly self-confident to overtly assertive.”

It is a good definition because it defines a term including and excluding the necessary conditions. It defines something concrete and observable, not a semantic form (it is easier to define “dominant behavior” than “dominance relationship”).

It states a necessary condition to distinguish it from a related technical term, aggressive behavior, even explaining a defining characteristic of the latter.

It does not include other terms needing a definition. It contains enough conditions to justify the use of the term—not too few, risking being synonymous with another term, and not too many, risking being too broad and losing its explanatory value.

It gives an example of its main characteristics in plain words. It does not presuppose any specialized knowledge of a reader to understand it. It is almost impossible not to agree with this definition unless, of course, one wants the term to describe something completely different (which is another matter altogether).

It accepts adjustments and improvements as new data becomes available, the mark of a good definition. In fact, we have modified it numerous times since its inception in the 1980s, thanks to the input of fellow researchers. It’s not the last word on this matter. It is, though, a solid tool to pave our way into increasingly more accurate explanations of a seemingly too complex reality for our brain to grasp.

It is not likely that we’ll find the truth, the only truth and nothing but the truth about behavior anytime soon, if ever, but we believe we can come close(r) to it by being meticulous in our observations, strict in our argumentations, modest in our generalizations, and prudent in our conclusions.

References

- Abrantes, R. 1997. The Evolution of Canine Social Behavior. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

- Abrantes, R. 1997. Dog Language. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

- Abrantes, R. 2014. Canine Muzzle Grasp Behavior—Advanced Dog Language.

- Abrantes, R. 2014. Canine Muzzle Nudge, Muzzle Grasp And Regurgitation Behavior.

- Abrantes, R. 2014. Why Do Dogs Like To Lick Our Faces?

- Akert, R. M., Aronson, E., & Wilson, T.D. (2010). Social Psychology (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Blair R. J. R. (2004) The roles of orbital frontal cortex in the modulation of antisocial behavior. Brain Cogn55:198–208.

- Bock, Gregory R. and Goode, Jamie A. (eds.) (1996). Genetics of Criminal and Antisocial Behavior. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Broom, M., Koenig, A., Borries, C. (2009).Variation in dominance hierarchies among group-living animals: modeling stability and the likelihood of coalitions, Behavioral Ecology, Volume 20, Issue 4, 1 July 2009, Pages 844–855, https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arp069

- Brown, C. (2015). Fish intelligence, sentience and ethics. Animal cognition, 18(1), 1-17.

- Copi, I., et al (2014) Introduction to Logic. Pearson Education Limited. Harlow.

- Coppinger, R. and Coppinger, L. 2001. Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. Scribner.

- Craig, I. W., Halton, K. E. (2009). Hum Genet (2009) 126:101–113.

- Darwin, C. 1872. The Expressions of the Emotions in Man and Animals. John Murray (the original edition).

- Dawkins, R. (2006) The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Fox, M. 1972. Behaviour of Wolves, Dogs, and Related Canids. Harper and Row.

- Javeed, Q. S. and Vidhate. N. J. (2012). A Study Of Aggression And Ego Strength Of Indoor Game Players And Outdoor Game Players. Indian Streams Research Journal, Volume 2, Issue. 7, Aug 2012.

- Lopez, Barry H. (1978). Of Wolves and Men. J. M. Dent and Sons Limited.

- Maynard Smith, J. (1972). Game Theory and The Evolution of Fighting. On Evolution. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-85224-223-9.

- Maynard Smith, J. (1982). Evolution and the Theory of Games. ISBN 0-521-28884-3.

- McFarland, D. (1982) The Oxford Companion to Animal Behaviour. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- McFarland, D. (1998) Animal Behaviour. Benjamin Cummings. 3rd ed.Maynard Smith, J, Harper, D. G. C., Brookfeld, J. F. Y. (1988) The Evolution of Aggression: Can Selection Generate Variability? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 319:557–570.

- McCauley, C. (2000) Some Things Psychologists Think They Know about Aggression and Violence. In Teaching About Violence, Vol 4. Spring 2000)

- Miles DR, Carey G (1997) Genetic and environmental architecture of human aggression. J Pers Soc Psychol72:207–217.

- Nash, J. F. (May 1950). Non-Cooperative Games (PDF). PhD thesis. Princeton University. Retrieved May 24,2015.Nelson, Randy Joe (ed.) (2006). Biology of Aggression. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mech, L. D. 1970. The wolf: the ecology and behavior of an endangered species. Doubleday Publishing Co., New York.

- Mech, L. David (1981). The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species. University of Minnesota Press.

- Mech, L. D. 1988. The arctic wolf: living with the pack. Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minn.

- Mech. L. D. and Boitani, L. 2003. Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. University of Chicago Press.

- Schacter, Daniel L. (2011). Psychology Second Edition. New York: Worth Publishers.

- Scott, J. P. and Fuller, J. L. 1998. Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog. University of Chicago Press.

- Shermer, M. (2004). The Science of Good and Evil. New York: Times Books.

- Siever LJ (2008) Neurobiology of aggression and violence. Am J Psychiatry 165:429–442

- Tremblay R. E., Hartup W. W., Archer, J. (2005) Developmental origins of aggression. Guildford Press, New York.

- Yamamoto H, Nagai K, Nakagawa H. (1984). Additional evidence that the suprachiasmatic nucleus is the center for regulation of insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. Brain Res304:237–241.

- Zimen, E. 1975. Social dynamics of the wolf pack. In The wild canids: their systematics, behavioral ecology and evolution. Edited by M. W. Fox. Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., New York. pp. 336-368.

- Zimen, E. 1982. A wolf pack sociogram. In Wolves of the world. Edited by F. H. Harrington, and P. C. Paquet. Noyes Publishers, Park Ridge, NJ.

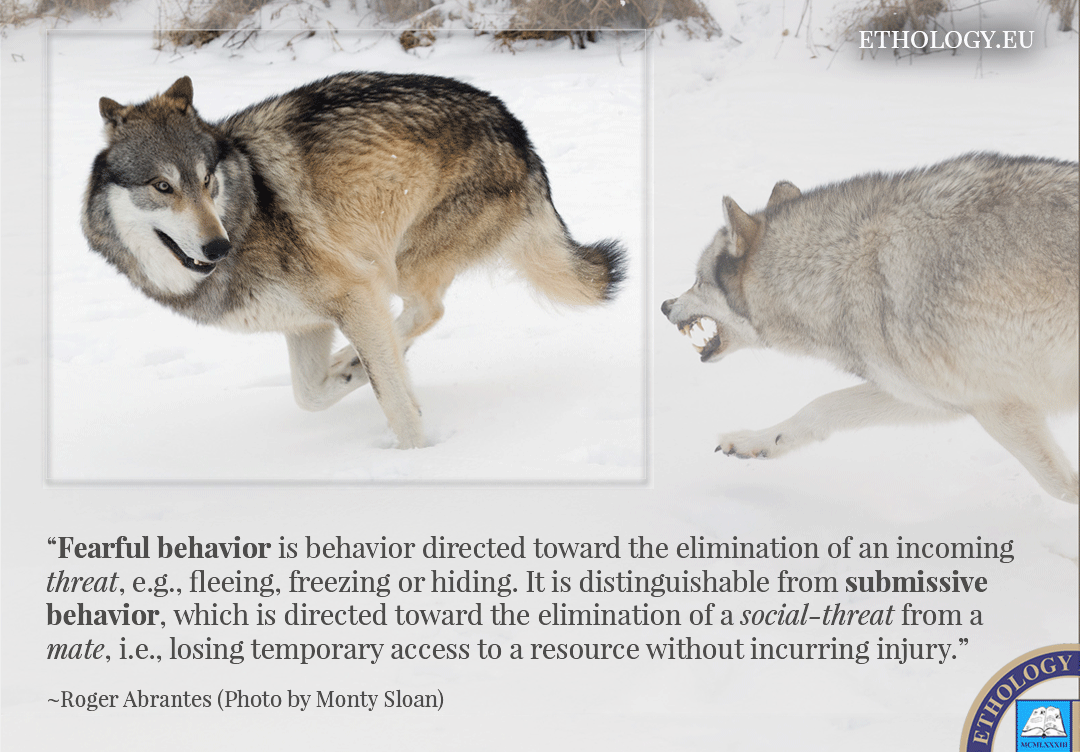

Featured image: Is this head-to-head confrontation a display of aggressive or dominant behavior? We need good definitions to decide correctly for one or the other (photo by unknown).

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.

Featured Course of the Week

The 20 Principles Animal training is a craft: half science and half art. This course and the included online book give you the 20 indispensable principles you must know to become a skilled animal trainer. It is the best crash course in animal training one can wish for.

Featured Price: € 148.00 € 98.00

16 Things You Should Stop Doing in Order to Be Happy with Your Dog

Here is a list of 16 things you should stop doing in order to make life with your dog happier and your relationship stronger. Difficult? Not at all. You just need to want to do it and then simply do it. You can begin as soon as you finish reading this.

1. Stop being fussy—don’t worry, be happy

Like most things in life, being a perfectionist has its advantages and disadvantages. When you own a dog, you tend to live by Murphy’s Law. Anything that can go wrong will go wrong. There are so many variables that things seldom go 100% the way you expect. You can and should plan and train, but be prepared to accept all kinds of variations, improvisations, and minor mishaps along the way—as long as no one is injured, of course. In most situations, less than perfect is better than good. Why worry about perfection—a concept that only exists in your mind?

2. Stop being too serious—have a laugh

If you don’t have a good sense of humor, don’t live with a dog. Dog ownership gives rise to many mishaps where laughter is the best way out. Mishaps are only embarrassing in our minds. Your dog doesn’t even know what embarrassment is, and you should follow its example. As long as no one gets hurt, just laugh at your and your dog’s mistakes.

3. Stop your desire to control everything—take it as it comes

When life with a dog is often dictated by Murphy’s Law, if you attempt to control your dog’s every move, you’ll end up with an ulcer or fall into a depression. Give up your need to control. Of course, you should be able to manage your dog’s behavior reasonably well for the sake of safety, but you should let go of anything that is not a matter of life or death. Reasonable rules are necessary and serve a purpose, but total control is unnecessary and self-defeating. Take it as it comes, and keep smiling!

4. Stop apportioning blame—move on

When things go wrong, and they will, I assure you, don’t waste your time apportioning blame. Was it your fault, the dog’s fault, or the neighbor’s cat’s fault? Who cares? Move on and, if you found the scenario all rather upsetting, try to foresee a similar situation in the future and avoid it. If it was no big deal, forget about it.

Featured Course of the Week

The 20 Principles Animal training is a craft: half science and half art. This course and the included online book give you the 20 indispensable principles you must know to become a skilled animal trainer. It is the best crash course in animal training one can wish for.

Featured Price: € 148.00 € 98.00

5. Stop believing in old wives’ tales—be critical

The world is full of irrational, unfounded old wives’ tales. These days, the Internet provides us with quick and easy access to a lot of valuable information—and a lot of junk as well: bad arguments, bad definitions, unsubstantiated claims, fallacies, emotional statements, pseudo-science, sales promotions, hidden political agendas, religious preaching, etc. Of course, in the name of freedom of expression, I believe everyone should be allowed to post whatever they like, even the purest and most refined crap—but both you and I also have the right to disregard it. Use your critical thinking. Don’t stop asking yourself, “How can that be?” and “How did he/she come to that conclusion?” Suspend judgment and action until you have had time to ponder on it and, if necessary, seek a second and third opinion. If the argument is sound and you like it, then do it. If the argument is sound, but you don’t like it, don’t do it and think more about it. If the argument is unsound, reject it and think no more about it. Make up your own mind and do what you think is right.

6. Stop caring about labels—be free

We are over-swamped by labels because labels sell, but they only sell if you buy them. Should you be a positive, ultra-positive, R+, R+P-, balanced, naturalistic, moralistic, conservative, realistic, progressive, clickerian or authoritarian dog owner? Stop caring about what label you should bear. When you enjoy a great moment with your dog, the label you bear is irrelevant. A label is a burden; it restricts you and takes away your freedom. Labels are for insecure people who need to hide behind an image. Believe in yourself, be the dog owner you want to be and you won’t need labels.

7. Stop caring about what others think—live your life

You spend very little time with most of the people you meet, significantly more with family and close friends, but you live your whole life with yourself. So, why care about what other people think about you as a dog owner or your dog’s behavior, when you probably won’t see them again or will only ever see them sporadically? If they like you and your dog, fine. If they don’t, it’s not your problem.

8. Stop complaining—don’t waste your time

You only have a problem when there is a discrepancy between the way things are and the way you expect them to be. If your expectations are realistic, try and do something about achieving them. If they’re not, stop complaining, it’s a waste of time and energy. If you can do something about it, do it. If you can’t, move on. Period.

9. Stop excusing yourself—be yourself

You don’t have to excuse yourself or your dog for the way you are. As long as you don’t bother anyone, you are both entitled to do what you like and be the way you are. You don’t need to be good at anything, whether it be Obedience, Agility, Musical Free Style, Heel Work to Music, Flyball, Frisbee Dog, Earth Dog, Ski-Joring, Bike-Joring, Earthdog, Rally-O, Weight Pulling, Carting, Schutzhund, Herding, Nose Work, Therapy, Field Trials, Dock Dogs, Dog Diving, Disc Dogs, Ultimate Air Dogs, Super Retriever, Splash Dogs, Hang Time, Lure Course Racing, Sled Dog Racing or Treibball; and you don’t need excuses as to why not. You don’t even need to excuse the fact that your dog can’t sit properly. Change what you want to change and can change. Don’t waste time and energy thinking about what you don’t want to, don’t need to or can’t change. Do whatever you and your dog enjoy so that both of you are happy. It’s as simple as that!

10. Stop feeling bad—act now

If you’re unhappy with any particular aspect of your life with your dog, do something to change it. Identify the problem, set a goal, make a plan and implement it. Feeling bad and guilty doesn’t help anyone—it doesn’t help you, your dog, or the cherished ones with whom you share your life.

11. Stop your urge to own—be a mate

The ownership of living beings is slavery; and, thankfully, slavery is abolished. Don’t regard yourself as the owner of your dog. Think of your dog as a younger and less experienced mate you are responsible for and needs your guidance. You don’t own your children, your partner or your friends either.

12. Stop dependency—untie your self

Love has nothing to do with dependency, obsession, and craving, quite the contrary. Love your dog but don’t create mutual dependency. Have a life of your own and give your dog some space. You and your dog are two independent individuals. Enjoy living together as free agents, not being addicted each other. Stop projecting yourself onto your dog.

13. Stop turning your dog into a substitute—show respect

A dog is a dog, and it is indeed a remarkable living being. Love it, enjoy its company, but don’t make it a substitute for a human partner, a friend, a child or a spouse. To expect anyone to be a substitute is the greatest disrespect you can show to a human as well as non-human animal—and to yourself. Stop letting your dog play a role for you and begin to love your dog as a dog.

14. Stop rationalizing—be truthful

All relationships are trades: you give and you take. There’s nothing wrong with that as long as there is a balance. Be honest with yourself: what does your dog give you and what do you give your dog? If you find that one of you is almost solely a giver or a taker, think about it and redress the balance. Your dog needs you, just as you need your dog and there’s nothing wrong with that, as long as you both are givers and takers. You didn’t get your dog just to save the poor, little creature. You got your dog so you could both enjoy a solid and productive partnership.

15. Stop wanting what you can’t have—be happy with what you’ve got

That is a very common human characteristic: you always want what you haven’t, and you are blind to all the good you do have. Your dog gives you a great deal. The two of you can be perfectly happy together, even if your dog is not particularly good at anything. It’s amazing how dog owners say they love their dogs, and yet they spend most of the time trying to change them. Focus on what you do have, not on what you don’t, appreciate it and be grateful for it.

16. Stop fighting yourself—follow your heart

There are many different ways of being a good dog owner, and yours is your own and different to everyone else’s. It’s your life. As long as you don’t harm anyone, live it the way that feels good for you. Listen to experts, ponder on their advice, but, at the end of the day, do what you feel is right for you, follow your heart. Be yourself.

Featured image:16 Things You Should Stop Doing in Order to Be Happy with Your Dog.

Learn more in our course Ethology and Behaviorism. Based on Roger Abrantes’ book “Animal Training My Way—The Merging of Ethology and Behaviorism,” this online course explains and teaches you how to create a stable and balanced relationship with any animal. It analyses the way we interact with our animals, combines the best of ethology and behaviorism and comes up with an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach to animal training. A state-of-the-art online course in four lessons including videos, a beautiful flip-pages book, and quizzes.

Fearful Behavior—the Making of a Definition

We have discussed aggressive behavior (1 and 2). We shall now examine fearful behavior beginning (as always) with a definition, but first, let us look at existing definitions.

“Fear is an unpleasant often strong emotion caused by anticipation or awareness of danger (Merriam-Webster).” As a dictionary definition (and that’s what it is), it works, but we need to be more precise.

“Fear is the unpleasant emotional state consisting of psychological and psychophysiological responses to a real external threat or danger.” (Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition). This definition is more precise than the former. However, to evaluate it correctly, we need first to define threat, particularly as to what real external threats are versus what the text leaves us presuming are not real threats. Second, the term unpleasant is vague. How can we observe psychological responses? We cannot. What we observe are behavioral changes, but that is not what the definition says. We can measure some psychophysiological responses, but I wouldn’t rely entirely and solely on them to analyze the consequences of a frightening experience.

When facing a threat, and flight is not possible, the next best option is to hide and freeze (photo from Molly’ s Just You Only Better).

“Fear is a normal emotional response to consciously recognized external sources of danger such as those often associated with loud noises, threatening gestures, strange people and thunderstorms; it is manifested in animals by flight, by attack or by cringing.” (Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary, 3 ed.). This definition contains the explanation of real threats (consciously recognized external sources of danger) that we missed above. It also gives us examples. Whether fear is manifested by flight, by attack or by cringing is controversial for an ethologist because these all have different functions. They appear together is this definition, probably because veterinarian science tends to classify behavior by symptoms (as is the practice in its field) and not function as evolutionary biologists (and ethologists) do. A fearful stimulus may trigger an attack (function=eliminate a threat), but an attack is aggressive behavior, even when defensive (function=eliminate competition), and cringing (a term not commonly used in the behavioral sciences) may signify submissive behavior, which is not the same as fearful behavior (function=eliminate a social threat).

“Fear is an emotion induced by a threat perceived by living entities, which causes a change in brain and organ function and ultimately a change in behavior, such as running away, hiding or freezing from traumatic events.” (Wikipedia). That is a good definition. It relates emotion with behavior, which is always sweet music to the ethologist’s ears, who prefers to deal with observable and measurable phenomena rather than the occult emotions. Running away, hiding or freezing are compatible as to function, so we have no problem with that. Traumatic events, on the other hand, requires an explanation.

Emotions are experienced and expressed at three different levels: (1) the psychological level, (2) the neurophysiological level, and (3) the behavioral level. All three aspects are present in all emotions. While psychologists focus on the first level and psychiatrists on the second, ethologists concentrate on the third.

“The main function of fear and anxiety is to act as a signal of danger, threat, or motivational conflict, and to trigger appropriate adaptive responses. For some authors, fear and anxiety are indistinguishable, whereas others believe that they are distinct phenomena.” (Steimer). That is a short, precise, and strong definition. It gives us the function of fear and points out an important distinction to a related term, anxiety, which “[…] is a generalized response to an unknown threat or internal conflict, whereas fear is focused on known external danger.”

Steimer’s and my definition are fully compatible. Here is mine:

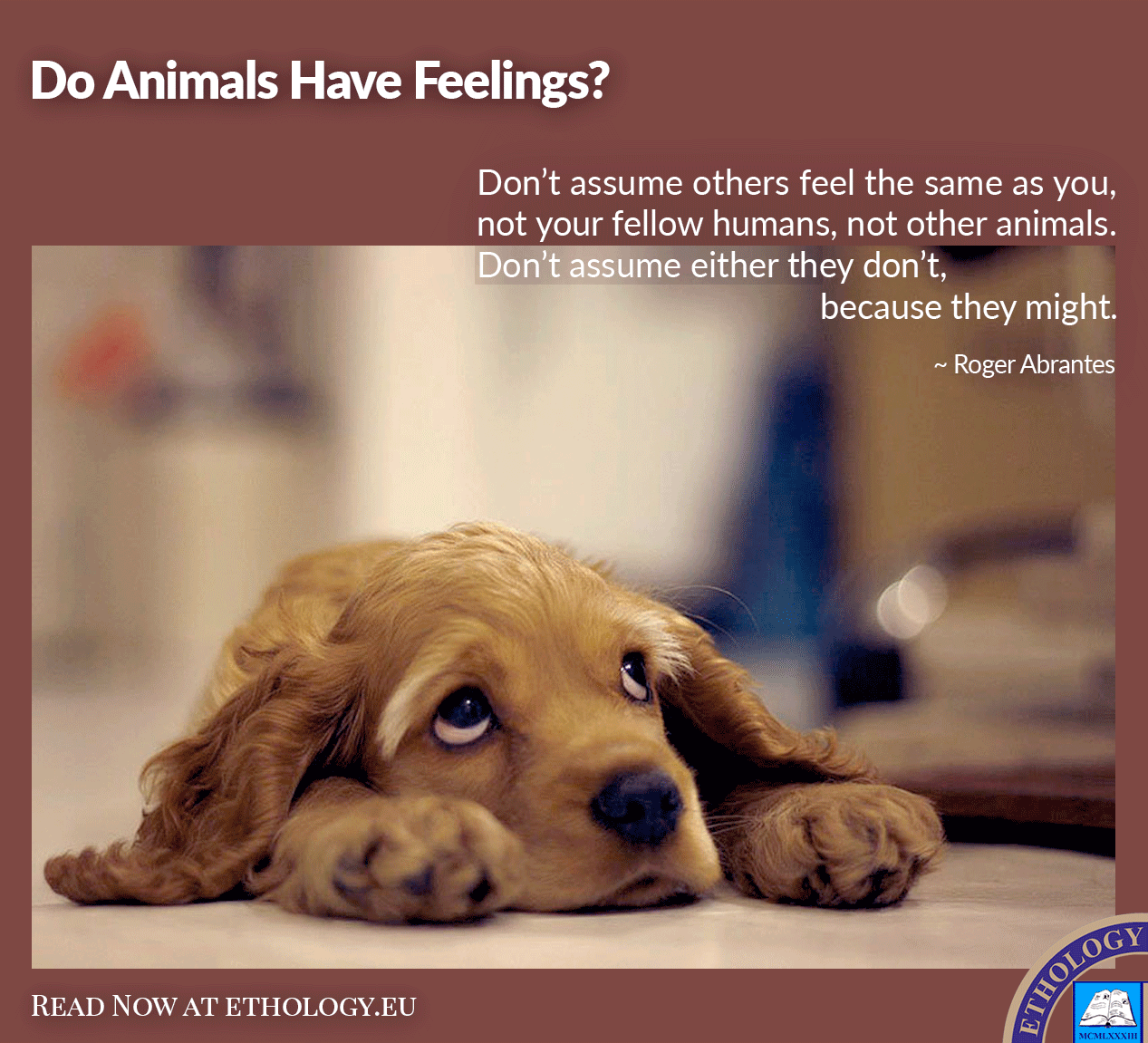

“Fearful behavior is behavior directed toward the elimination of an incoming threat, e.g., fleeing, freezing, or hiding. Submissive behavior is behavior directed toward the elimination of a social-threat from a mate, i.e., losing temporary access to a resource without incurring injury, e.g., and highly depending on species, lying down on the back, assuming a low-profile body posture, or turning the neck away.”

My definition is identical to Steimer’s, only focusing on the behavior and compiling all triggering factors under one label, threats. Moreover, I prefer to pinpoint the distinction to the related submissive behavior (instead of anxiety). Mine is a more extreme ethological definition and has the advantage of adding an explanation of submissive behavior. Steiner’s has the advantage of relating to anxiety and is more likely to be adopted by human psychologists and psychiatrists.

Both Steimer’s and my definition require a definition of threat. Steimer does not explicitly give us one. However, I do, and one, which is compatible with both our definitions.

“A threat is everything that may harm, inflict pain or injury, or decrease an individual’s chance of survival. A social-threat is everything that may result in the temporary loss of a resource and may cause submissive behavior or flight, without the submissive individual incurring injury.”

When facing a social-threat, submissive behavior is the best option. This dog shows what ethologists call active-submissive behavior (photo from safekidssafedogs).

I’m compelled (Steimer is not) to distinguish between threat and social-threat because, in my definition, I pinpointed the difference between fearful and submissive behavior.

I have used a term that also needs a definition, namely, mate.

“Mates are two or more animals that live close together and depend on one another for survival. Aliens are two or more animals that do not live close together and do not depend on one another for survival.”

McFarland explains fear as a motivational state triggered by particular stimuli that give rise to defensive behavior or escape. Fear is one of the primary motivators because of its life-saving function. Newborns and infants show innate fear responses to particular stimuli that may harm them. Also, environmental disturbances require habituation. Their fear of novelty loses its strength gradually and only comes back much later when trying new ways amounts to the spending of more energy (heavily penalized in nature) than doing it as they always have done.

Fear sometimes occurs in conjunction with other motivators. Approach-escape conflicts are typical examples and often result in displacement behavior as, for instance, self-grooming. We may argue that displacement behavior indicates the kind of fear that psychologists call anxiety. However, ethologists need not introduce a new term because the definition of fear includes the biological aspects of anxiety.

Even if anxiety and fear are probably distinct emotional states, there may be some common aspects in their brain and behavioral mechanisms. As Barlow says, anxiety may just be a more elaborate form of fear enabling the individual with an increased capacity to adapt and plan for the future. In Steimer’s words, “If this is the case, we can expect that part of the fear-mediating mechanisms elaborated during evolution to protect the individual from an immediate danger have been somehow ‘recycled’ to develop the sophisticated systems required to protect us from more distant or virtual threats.”

When describing animal behavior, it is more useful to refer to fear and fearful behavior than anxiety. Additionally, we must bear in mind that fearful is an adjective of behavior. To label a particular animal as fearful might be to go over the top. An animal may show fearful behavior, and rightly so, in certain situations and not in others.

Fear and fearful behavior evolved with the vital function of protecting the individual and are, therefore, mechanisms, which we may presume to have a strong genetic correlation. Animals of different species show fearful behavior to different stimuli and in different degrees. It is natural and normal for almost all animals (if not all) to get startled by a loud noise or a sudden movement. Horses and Guinea pigs get startled by more and different stimuli than dogs because they are prey animals, but they come over it quickly. They are not more fearful animals per se—they are just different, and comparison at this level is meaningless.

Two essential aspects of fear: (1) Fearful behavior has genetic and learned components, and (2) not seldom, our pets show fearful behavior because we have taught them that without being aware. These are the topics for the following article.

References

- Barlow, D. H. (2000). Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. Am Psychol. 55:1247–1263.

- LeDoux, J. (1998). The Emotional Brain. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- McFarland D. (1987). The Oxford Companion to Animal Behaviour. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Steimer, T. (2002). The biology of fear- and anxiety-related behaviors. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Sep 2002; 4(3): 231–249.

- Strongman, K. T. (1996). The Psychology of Emotion. Theories of Emotion in Perspective. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & sons.

- Watson, J. B. (1970). Behaviorism. 7th ed. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

Featured picture: Fearful and submissive behavior overlap. Fearful behavior is always submissive but it makes sense to distinguish between the two because some submissive behavior is not particularly fearful (rather respectful, in human terms). This excellent photo by Monty Sloan shows this overlap of motivational factors. The highlighted wolf shows more submissive and less fearful behavior than expected, given the clear aggressive and dominant display of its opponent. That is a sure indicator that they are mates, i.e., belong to the same pack.

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.

Aggressive Behavior—the Making of a Definition

Aggressive and dominant (self-confident) behavior (picture from dogsquad).

Aggressive and submissive behavior (not fearful).

This is the behavior a cornered dog shows when pacifying, submission and flight don’t work (picture from doggies).

Aggressive and submissive behavior (ears down, long mouth, smaller eyes) (picture Cesar’sWay).

Growling and snarling are also aggressive behaviors (picture askmen)

Contrary to what you might suppose, aggressive behavior is difficult to define. “Lack of agreement regarding definitions of aggressive behavior has been a significant impediment to the progress of research in this area,” writes Nelson in 2005 in his big book ‘Biology of Aggression.’

Why is a good definition necessary? Because only then do we know what we are discussing.

I have never been quite satisfied with my own definition, and it nags me, worse than a mosquito bite, when I can’t come up with a good definition. I have often returned to it changing a comma or two to see if it improved. Alas, to no avail, updated versions were marginally better, but not resoundingly so.

My original definition, let me remind you, was: “Aggressiveness (or aggressive behavior) is behavior directed toward the elimination of competition. It can range from displays of intent, like growling, roaring and stamping to injuring behavior like biting, staging, kicking.”

Not bad, but could be better. I checked many other definitions to analyze their strengths and shortcomings, hoping to get the necessary inspiration to come up with a really good definition.

A— “Aggressive behavior is behavior that causes physical or emotional harm to others, or threatens to. It can range from verbal abuse to the destruction of a victim’s personal property” (www.healthline.com/health/).

Not bad, but not precise enough to use in the biological sciences.

B— “Aggression is a forceful behavior, action, or attitude that is expressed physically, verbally, or symbolically. It may arise from innate drives or occur as a defense mechanism, often resulting from a threatened ego. It is manifested by either constructive or destructive acts directed toward oneself or against others (Mosby’s Medical Dictionary, 8th edition).”

Not bad either, though weakened by the passive voice. It recurs to terms needing strong definitions as well, i.e. drive, defense mechanism. Finally, it is a bit too psychological for the evolutionary biologist—what is a threatened ego?

C— “Aggression is behavior that is angry and destructive and intended to be injurious, physically or emotionally, and aimed at domination of one animal by another. It may be manifested by overt attacking and destructive behavior or by covert attitudes of hostility and obstructionism. The most common behavioral problem seen in dogs.” (http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Aggressive+Behaviour).

This one is not good. It is more a list of synonyms (angry, destructive, hostility, obstructionism) than a definition. It mixes concepts together too easily (aggression and domination?). Finally, the most common problem in dogs in our files (over 10,000 of them) is home alone problems, not aggressive (whatever that is) behavior.

D— “Aggressive people often uses anger, aggressive body language […] “(http://changingminds.org/techniques/assertiveness/aggressive_behavior.htm).

This one, we won’t waste any more time with. A definition that uses the definiendum is not a definition.

E— “Aggression is a response to something/someone the animal perceives as a threat. Aggression is used to protect the animal through the use of aggressive displays (growling, barking, tooth displays, etc.) or protect the animal through aggressive acts (biting). Aggressive behavior is most frequently caused by fear.” (somewhere on the Internet).

This one is not good either. Again, it uses the definiendum in the definition. We miss the definition of threat to be able to analyze the sentence conclusively. More seriously, it states that aggression is caused by fear, which from an evolutionary point of view doesn’t make sense. Fear does not elicit aggressive behavior. It would have been a lethal strategy that natural selection would have eradicated swiftly and once and for all. A cornered animal does not show aggressive behavior because it is fearful. It does so because its natural responses to a fear-eliciting stimulus (pacifying, submission, flight) don’t work.

F— “Aggression is defined as behavior which produced or was intended to produce physical injury or pain in another person.” (Nelson, R. .J. 2005. Biology of Aggression. Oxford Univ. Press).

This is a much better definition, but it could be more explanatory.

So, after yet another round of deliberation, here follows my suggestion.

“Aggressive behavior is behavior directed toward the elimination of competition from an opponent, by injuring it, inflicting it pain, or giving it a reliable warning of such impending consequences if it takes no evasive action. It is distinguishable from dominant behavior in as much as the latter does not include harmful behaviors though it may require some degree of forceful measures. Aggressive behavior ranges from reliable warnings of impending damaging behavior such as growling, roaring, and stamping, to injurious behaviors such as biting, staging, and kicking. Predatory behavior is not aggressive behavior.”

This is much better than earlier versions, and it complies with all the requirements for a good definition. Thus:

- It defines something concrete and observable.

- It states a necessary condition to distinguish it from a related technical term, dominant behavior, even explaining a characteristic of the latter.

- It does not include other terms needing a definition.

- It includes enough conditions to justify the use of the term, not too few to risk being synonymous with another term, and not too many to risk losing its explanatory value by being too encompassing.

- It gives examples of what is and is not aggressive behavior.

- It does not presuppose any special knowledge of the reader to understand it.

This is a good definition because it defines the term, including and excluding the necessary conditions. Whether it will be the last word on the matter is another story. I’m sure it won’t. There is always room for improvement. A good definition must also be able to accept reviews imposed by newer discoveries. Until then, I’m happier with this one than with any earlier versions. Aren’t you?

Learn more in our course Agonistic Behavior. Agonistic Behavior is all forms of aggression, threat, fear, pacifying behavior, fight or flight, arising from confrontations between individuals of the same species. This course gives you the scientific definitions and facts.