The canine muzzle grasp behavior is an interesting behavior I’ve seen in many canids including our domestic dogs. It’s a behavior that scares many dog owners who believe it signals unconditional and uninhibited aggression. It doesn’t.

The muzzle grasp is yet one of those fascinating behavior that developed and evolved because it conferred a higher fitness to those who practiced it.

The function of this behavior is to confirm a relationship rather than to settle a dispute. The more self-confident dog will muzzle-grasp a more insecure one and thus assert its social position. The latter will not resist the muzzle grasp. On the contrary, it is often the more insecure that invites its opponent to muzzle-grasp it. Even though we sometimes see this behavior at the end of a dispute, wolves and dogs only use it toward individuals they know well (teammates) almost as a way of saying, “You’re still a cub (pup).” The dispute itself is not serious, just a low-key challenge, perhaps over access to a particular resource. Youngsters, cubs, and pups sometimes solicit adults to muzzle-grasp them. This behavior appears to be reassuring for them, a means of saying, “I’m still your cub (pup).”

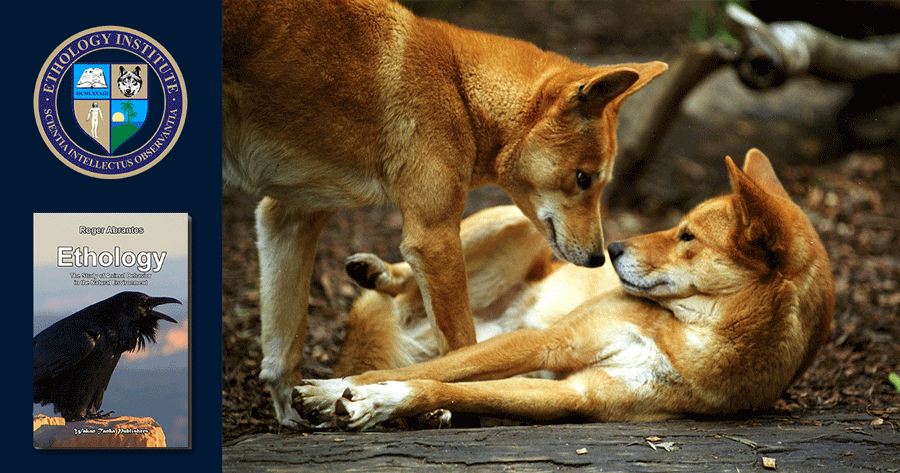

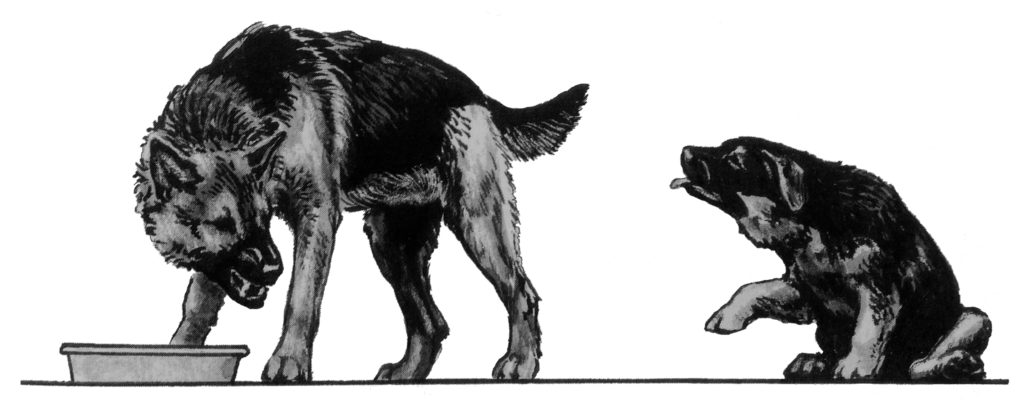

Dogs also show the muzzle grasp behavior (photo by Marco de Kloet).

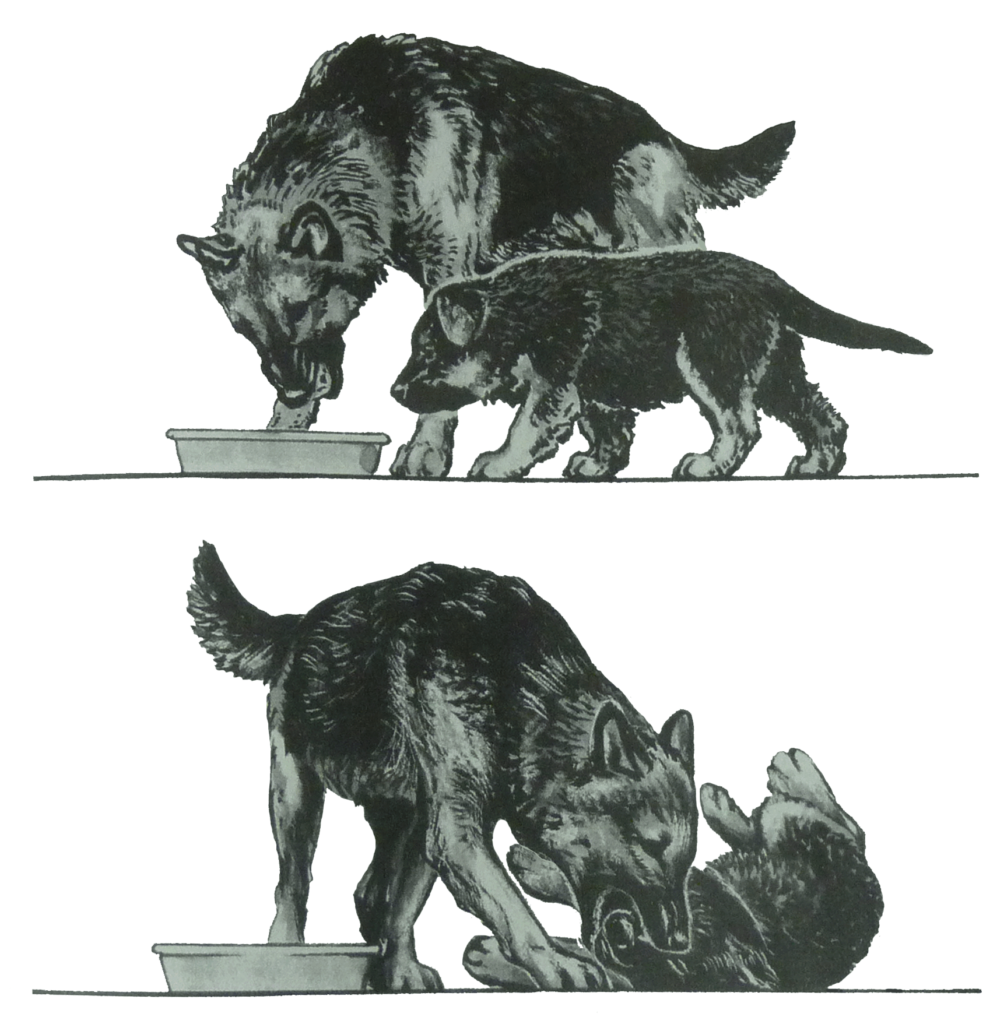

When used to settle a dispute, a muzzle grasp looks more violent and ends with the muzzle-grasped individual showing what we ethologists call passive-submissive behavior, i.e. laying on its back.

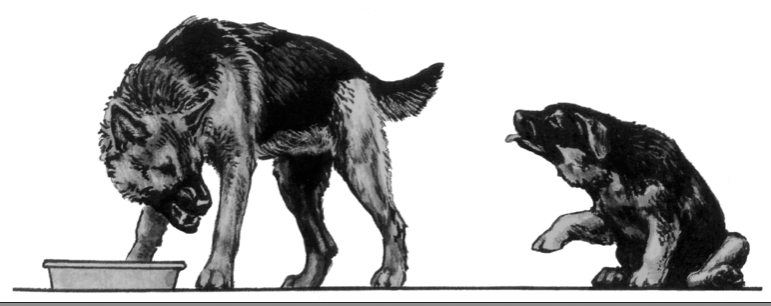

The muzzle grasp behavior emerges early on. Canine mothers muzzle-grasp their puppies (sometimes accompanied by a growl) to deter them from suckling during weaning. At first, her behavior frightens them and they may whimper excessively, even if the mother has not harmed them the least. Later on, when grasped by the muzzle, the puppy immediately lies down with its belly up. Previously, it was assumed that the mother needed to pin the puppy to the ground, but this is not the case as most puppies lie down voluntarily. Cubs and pups also muzzle-grasp one another during play, typically between six and nine weeks of age. A muzzle grasp does not involve biting, just grasping. This behavior helps develop a relationship of trust between both parties: “We don’t hurt one another.”

Cubs and pups muzzle grasp one another during play (photo by Monty Sloan).

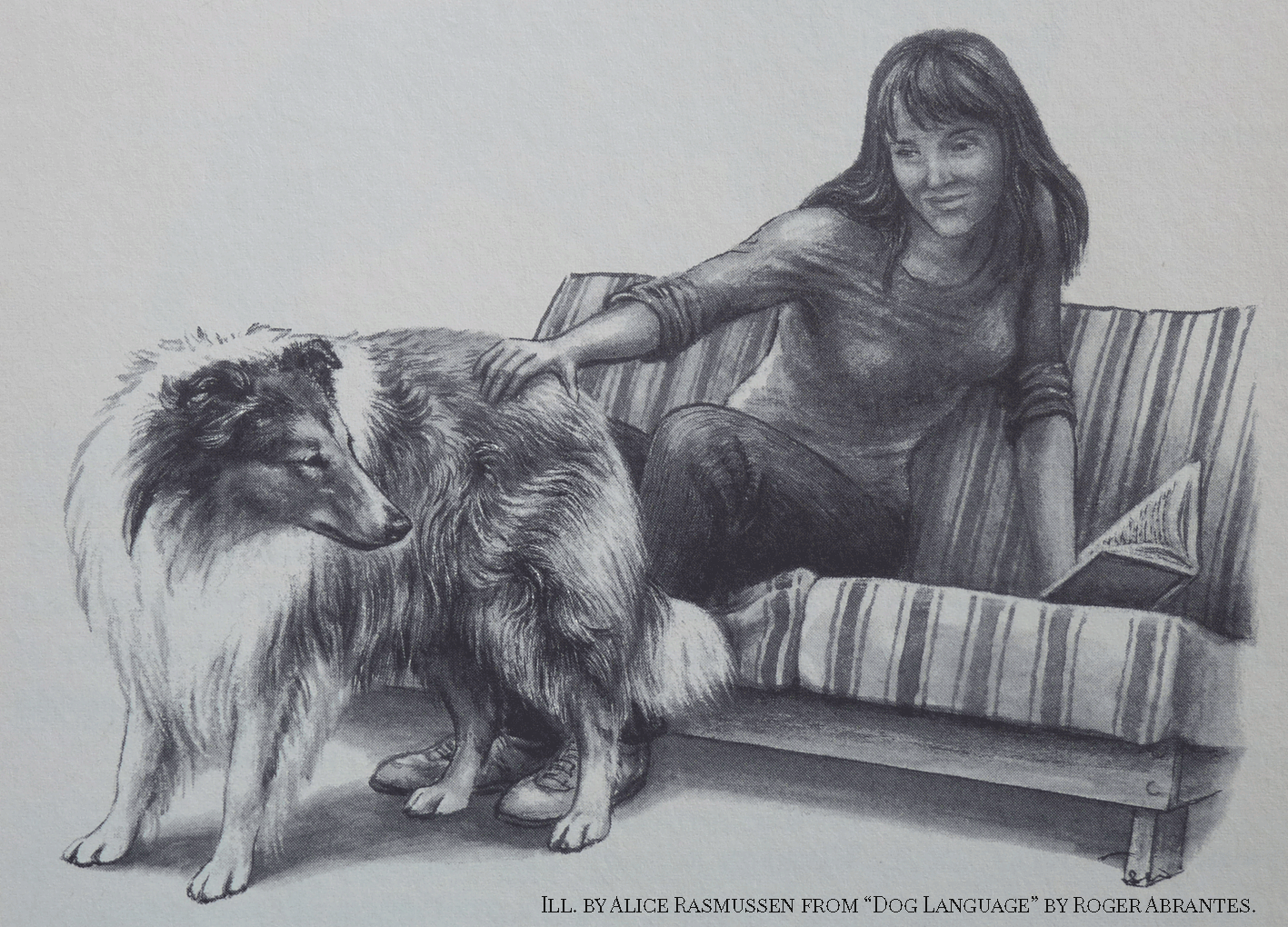

Domestic dogs sometimes approach their owners puffing to them gently with their noses. By grasping them gently around the muzzle, we reaffirm we accept them. We show self-control and that they can trust us. After being muzzle grasped for a while, the dog will usually show a nose lick, maybe yawn and then walk calmly away. It’s like the dog saying, “I’m still your puppy” and the owner saying, “I know and I’ll take good care of you.” Yawn back and all is good.

Speaking dog language helps promote an understanding between our dogs and us. It may make us look silly, but who cares? I don’t, do you?

Featured image: Muzzle grasp in adult wolves (photo by Monty Sloan).

Featured Course of the Week

Ethology Ethology studies animal behavior in its natural environment. It is one of the fundamental courses in your curriculum. A reliable knowledge of animal behavior is the basis to create a satisfying relationship with any animal we train.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.