Introduction: the problem

The main difficulty in some learning processes is to reinforce the right behavior at the right time, which bad teachers, bad parents, and bad trainers do not master (bad means inefficient, and it is not a moral judgment).

If you ask, “should we reinforce the effort or the result?” you are liable to get as many answers supporting the one opinion as for the other. Supporters of the effort system sustain that reinforcing results creates emotional problems when one doesn’t succeed and decreases the rate of even trying. Advocates of the result method defend that reinforcing the effort encourages sloppiness and cheating.

I shall argue in the following for and against both theories and prove that it is not a question of either/or, rather of defining clearly our criteria, processes, and goals.

I shall compare the learning of some skills in dogs and humans because the principles are the same. The difference between them and us is one “of degree, not of kind,” as Darwin put it.

I will use SMAF to describe some processes accurately where I find it advantageously. If you are not proficient in SMAF, and you’d like to be, please read “Mission SMAF— Bringing Scientific Precision Into Animal Training.”

When a reinforcer is a disguised signal

Much of my personal work with dogs (and rats and Guinea Pigs) is and has been detection work, mainly narcotics and explosives, but also person search, tobacco, and other scent detection work. One of the first signals I teach the animals is a disguised reinforcer.

With dogs, I use the sound ‘Yes’ (the English word). The signal part of this signal/reinforcer means, “continue what you’re doing,” and the reinforcer part, “we’re OK, mate, doing well, keep up.” That is a signal that becomes a reinforcer: Continue,sound(yes) that becomes a “!+sound”(yes).

The difference between the most used “!±sound”(good-job) and “!+sound”(yes) is that the former is associated and maintained with “!-treat”(small food treat) and “!-body(friendly body language); and the latter with a behavior that will eventually produce “!-treat”. The searching behavior does not provide a treat, but continuing searching will eventually (find or no find). That is why “!+sound”(yes) is a disguised Continue,sound(yes) or the other way around.

Search’ means “Go and find out whether there is a thing out there.” The signal ‘Search’ (Search,sound) does not mean ‘Find the thing.’ Sometimes (most of the time) there’s nothing to find.

Why do I need this interbreeding between a signal and a reinforcer?

Because the signal ‘Search’ (Search,sound) does not mean ‘Find the thing.’ Sometimes (most of the time) there’s nothing to find, which is good for all of us (airports and the likes are not that full of drugs and explosives).

So, what does Search,sound mean? What am I reinforcing? The effort?

No, I’m not. We have to be careful because if we focus on reinforcing the effort, we may end up reinforcing the animal just strolling around, or any other accidental or coincidental behavior.

I am still reinforcing the result. ‘Search’ means “Go and find out whether there is a thing out there.” ‘Thing’ is everything that I have taught the dog to search and locate for me, e.g., cocaine, hash, TNT, C4.

“Go and find out whether there is a thing out there” leaves us with two options equally successful: ‘here’ and ‘clear.’ When there is a thing, the dog answers ‘here’ by pointing at its apparent location (I have taught it that behavior). When there is no thing, that is precisely what I want the animal to tell me: the dog answers ‘clear’ by coming back to me (again because I have taught it that). We have two signals and two behaviors:

Thing,scent => dog points (‘here’ behavior).

∅Thing,scent => dog comes back to me (‘clear’ behavior).

The signals are part of the environment. I do not give them, which does not matter: a signal (SD) is a signal.(1) An SD is a stimulus associated with a particular behavior and a particular consequence or class of consequences. When we have two of them, we expect two different behaviors, and when there is none, we expect no behavior. What fools us, here, is that, in detection work, we always have one and only one SD, either one or the other. Having none is impossible. Either we have a scent, or we don’t, which means that either we have Thing,scent or we have ∅Thing,scent, requiring two different behaviors as usually. The one SD is the absence of the other.

Traditionally, we don’t reinforce a search that doesn’t produce a positive indication. To avoid extinguishing the behavior, we use ‘controlled positive samples’ (a drug or an explosive, we know it is there because we have placed it there to give the animal a possibility to obtain a reinforcer).

That is a correct solution, except that it teaches the dog that the criterion for success is ‘to find’ and not ‘not to find,’ which is not true. ‘Not to find’ (because there is nothing) is as good as ‘to find.’ The tricky part is, therefore, to reinforce the ‘clear’ and how to do it to avoid sloppiness (strolling around) and cheating.

Let us analyze the problem systematically

The following process does not give us any problems:

Search,sound => Dog searches => “!+sound”(yes) or Continue,sound(yes) => Dog searches => Dog finds thing (Thing,scent) => Dog points (‘here’ behavior) => “!±sound”(good-job) + “!-treat”.

No problem, but what, then, when there is no thing (∅Thing,scent)? If I don’t reinforce the searching behavior, I might extinguish it. In that situation, I reinforce the searching with “!+sound”(yes):

“Search,sound” => Dog searches => “!+sound”(yes) => Dog searches => ∅Thing,scent => Dog comes back to me (‘clear’ behavior) => “!±sound”(good-job). */And I can also give “!-treat”*/

Looks good, but it poses us some compelling questions:

How do I know the dog is searching versus strolling around (sloppiness)?

How do I know I am reinforcing the searching behavior?

If I reinforce the dog coming back to me, then, next time I risk that the dog will take a quick round and get to me right away: that is the problem. I want the dog to return to me only when it finds nothing (the same as didn’t find anything).

Problems:

To reinforce the searching behavior.

To identify the searching behavior versus strolling around (sloppiness). How can I make sure that the dog always searches and never only rambles around?

Solution:

Reinforcing the searching behavior with “!+sound”(yes) works. OK.

Remaining problem:

I have to reinforce the ‘clear’ behavior (coming back to me), but how can I make sure that the dog always searches and never strolls around (avoid sloppiness)?

How can I make sure that the dog has no interest in being sloppy or cheating me?

Solution:

To teach the dog that reinforcers are available if and only if:

1. The dog finds the thing. Thing,scent => Dog sits => “!±sound”(good-job) + “!-treat”.

2. The dog does not ever miss a thing. ∅Thing,scent => Dog comes back to me => “!±sound”(good-job) + “!-treat”.

Training:

I teach the dog gradually to find things until I reach a predetermined low concentration of the target scent (my DLO—Desired Learning Objective). In this phase of training, there is always one thing to find. After ten consecutive successful finds (my criterium and quality control measure), all producing reinforcers for both the searching (“!+sound”(yes)) and the finding (“!+sound” + “!-treat”), I set up a situation with no thing (∅Thing,scent). The dog searches and doesn’t find anything. I reinforce the searching and the finding (no-thing) as previously. Next set-up, I make sure there is a thing to find, and I reinforce both searching and finding.

I never reinforce not-finding a thing that is there or finding a thing that is not there (yes, the last one is an apparent paradox).

Consequence: the only undesirable situations for a dog are: (1) not-finding a thing that is there (the dog did not indicate Thing,scent), or (2) indicating a thing that is not there (the dog indicates ∅Thing,scent).

(1) Thing,scent => Dog comes back to me (‘clear’ behavior) => [?±sound] + [?-treat].

Or:

(2) ∅Thing,scent => Dog points (‘here’ behavior) => [?±sound] + [?-treat].

That is (negatively) inhibiting negligence, but since it proves to increase the intensity of the searching, we cannot qualify it as an inhibitor. Therefore, we call it a non-reinforcer: “∅±sound”, “∅-treat”.

In the first case:

Thing,scent => Dog comes back to me => [?±sound] + [?-treat].

Becomes:

Thing,scent => Dog comes back to me => “∅±sound”, “∅-treat”.

Then:

Thing,scent => Dog comes back to me => “∅±sound”, “∅-treat” => Dog searches (more intensively) => Thing,scent => Dog points (‘here’ behavior) => “!±sound” + “!-treat”.

In the second case, I have to be 100% sure that there is indeed no-thing. The training area must be free of any scent remotely similar to the scent we are training (Thing,scent). Particularly in the first phases of the training process, this is imperative, and a trainer who misses that is committing major negligence.

Should the dog, nevertheless, show ‘here’ for ∅Thing,scent, then we can use the same procedure as above:

∅Thing,scent => Dog shows ‘here’ behavior => “∅±sound”, “∅-treat” => Dog searches (more intensively) => ∅Thing,scent => Dog comes back to me (‘clear’ behavior) => “!±sound” + “!-treat”.

What if later the dog doesn’t find a thing that is there in a lower concentration than the one I used for training, or masked by other scents?

No problem—that is not the dog’s fault. I didn’t train it for it. The dog doesn’t know that it is committing a mistake by giving me a (wrong) ‘clear.’ As far as the dog is concerned, the room is clear. For the dog, it is a ‘clear’: ∅Thing,scent => Dog comes back to me => “!±sound” + “!-treat”. The dog was not strolling around and is not cheating me.

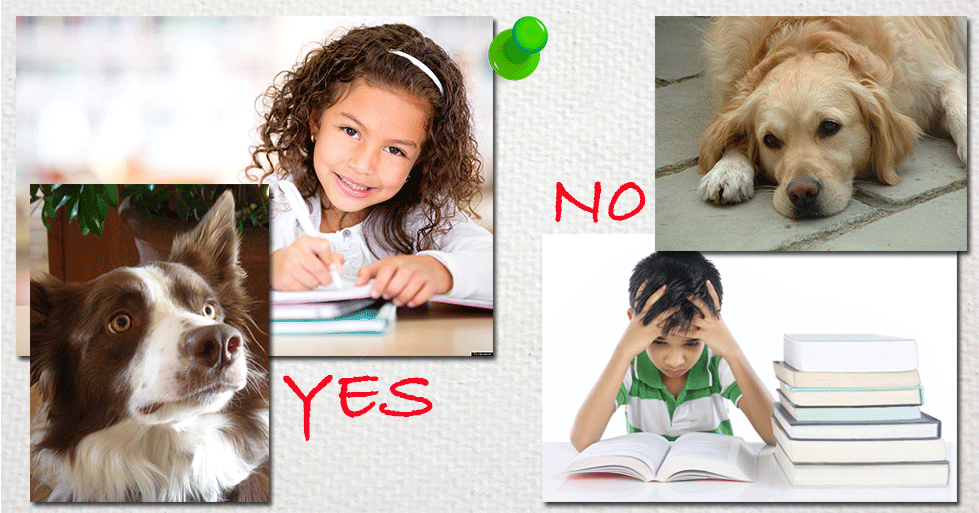

Comparing to humans

I reinforce the behavior of the child trying to solve a math problem. Yes, we must always reinforce (or inhibit) a behavior, not the individual. “Well done, but you got it wrong because…” The solution may be incorrect, but the method was correct. Then, it is all a question of training. More or better training will eliminate the ‘wrong.’ Maybe, it was caused by a too abrupt increase in the difficulty curve of the problem (which is the teacher’s problem). We are not reinforcing trying; we are reinforcing the correct use of a method (a desired process).

Why reinforce the process?

We must reinforce the process because of its emotional consequences. The dog and the child must accept the challenge, must want to be tried and to be able to give their best in solving a problem.

Are we reinforcing the effort rather than the success?

No, we are not. Reinforcing the effort rather than the result can and will lead to false positives. The animal indicates something that it is not there because it associates the reinforcer with the behavior, not the thing. Children give us three-four consecutive, quick and wrong answers if we reinforce the trying, not the process (thinking before answering).

We reinforce the result (success) only. When the dog doesn’t find because there’s nothing to find, that is a success. When the dog doesn’t find because the concentration was too low, that is a success because ‘too low’ is here equal to ‘no-thing.’ When the child gets it wrong, it is because the exercise exceeded the actual capacity of the child (not trained to that). No place to hide for trainers, coaches, teachers, and parents.

We are still reinforcing success and exactly what we trained the dog and the child to do. We don’t say to the child, “Well, you tried hard enough, good.” We say, ” Well done; you did everything correctly. You just didn’t get it right because you didn’t know that x=2y-z and you couldn’t know it.” Next time, the child gets it right because now she knows it; and if not, it is because x=2y-z exceeds the capacity of that particular child, at that particular moment, in which case, there’s nothing to do about it.

The same with the dog: the dog (probably) will not indicate 0.01g of cocaine because I trained it to go as low as 0.1g. When I reinforce the dog’s ‘clear,’ I say, “Well done, you did everything correctly, you just didn’t get it right because you didn’t know that 0.01g cocaine is still the thing.” Now, I train the dog that ‘thing’ means ‘down to 0.01g cocaine’ and either the dog can do it or it cannot. If it can, good. If it cannot, there’s nothing we can do about it.

Conclusion

We reinforce result, success, not the effort, not trying. We must define and recognize success, establish clear criteria, plan a progressive approach to our goal, and design a gradual path to our objective, including a steady rise in the task’s difficulty or complexity. Yes, we reinforce success in accomplishing each and every of the multiple incremental steps—barely perceptible if needed be—toward our ultimate objective, treating each as a discrete goal.

For any given skill we teach, we must recognize limits and limitations in ourselves, in the animal species we work with, the individuals we tutor. We must realize when we cannot develop a skill any further—push boundaries any farther—and when someone, human or otherwise, cannot give us more than what we get; and be content with that.

________

Footnotes

1 Strictly speaking, the scent, which the detection dog searches, is not a signal, but a cue, because it is not intentional. In this context, however, it is an SD because we have conditioned it to be so, and we can, therefore, call it a signal. Please, see “Signal and Cue—What is the Difference?”

Featured image: Learning is a complex process The main difficulty in some learning processes is to reinforce the right behavior at the right time, which bad teachers, bad parents, and bad trainers do not master. We must reinforce the process because of its emotional consequences. The dog and the child must accept the challenge, want to be challenged, to be able to give their best in solving the problem, not giving up.

Featured Course of the Week

The 20 Principles Animal training is a craft: half science and half art. This course and the included online book give you the 20 indispensable principles you must know to become a skilled animal trainer. It is the best crash course in animal training one can wish for.

Featured Price: € 148.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Canine Scent Detection, which will enable you to pursue further goals, such as becoming a substance detection team or a SAR unit. You complete the course by passing the double-blind test locating a hidden scent. You take the theory online in the first three lessons. In lesson four, you train yourself and your dog, step by step until reaching your goal. We will assign you a qualified tutor to guide you, one-on-one, either on-site or by video conferencing.