Did she cheat me? Did she manipulate me? Was it a proof that my English Cocker Spaniel had a sense of self-respect, that dogs behave intelligently?

It happened long ago, but I still think about it, trying to find a plausible and scientifically correct explanation. My dogs have always been fun dogs, independent and skillful, but manipulative and naughty at the same time. It’s my fault. I’ve brought them up to be that way. I trained them because at the time (the beginning of the 1980s) I was keen on demonstrating that there were other ways of training dogs than the traditional, mostly compulsory and often forceful methods of the old school. Since I believed (and still do) that the best way to have someone change is not by forcing, persuading or convincing, but rather by showing attractive results, I trained my dogs to help me in this quest, and none more than Petrine, my female, red English Cocker Spaniel did so.

At the time, there was a very popular dog training series on TV called “No Bad Dogs the Woodhouse Way” with the unforgettable Barbara Woodhouse. Those of a certain age will chuckle nostalgically when they hear inimitable “walkies.” Mrs. Woodhouse, born in 1910, was a charming, efficient lady who loved animals. She was not mean; it was just her methods that were forceful to say the least. Does this sound familiar? History repeats itself, as we well know!

Instead of attacking her and her methods personally, or trying to argue for ways I thought were better, I found a more convenient strategy: to channel the interest in dog training that Mrs. Woodhouse generated and present my own way as an alternative. Of course, I had to show results. I had to be able to teach the dogs the same Mrs. Woodhouse so efficiently taught them. If I was successful, and my methods were not only as efficient but more attractive, they would win the public’s favor. If I couldn’t achieve the same results as her, my way would not win. I went for it, confident that I could make dogs as “obedient” as Mrs. Woodhouse did, but using my own methods. To allow for an obvious comparison, I even used the terminology of the time, which I later felt entitled to change when my first book came out in 1984: from there on a “command” became a “signal,” “obedience” became “cooperation,” and “praise” became a “reinforcer.”

So, Petrine and I did a lot of “obedience” training, even if we weren’t too keen on the fastidiousness of the process. We trained using motivation, treats, facial expressions as reinforcers, the word “dygtig,” later to be called a semi-conditioned verbal reinforcer, and sometimes a whistle as a conditioned positive reinforcer (the precursor of the clicker); and together we won several obedience competitions.

At the time, you didn’t see many Cockers competing, and our victories did help to prove my point, but our achievements weren’t exactly a big surprise. They were more like appetizers. What really did it was when we won a hunting-dog competition. That caused quite some stir in the dog-training community of that time because we beat all the smart, green clad hunters with their pointers and the like. At the time, it was unthinkable that an English Cocker Spaniel (not only red, but female too!) and a longhaired, bearded, young fellow (in worn-out Levi’s and clogs just to top it off) could beat the establishment. Well, we did! That day of fame and infamy set me on a career path I could never have imagined. Training in a new way, the “psychology rather than power” way rather than the Woodhouse way, we made it into newspapers, magazines, TV and radio, and to be on TV was a big thing at the time. Inevitably, we were heroes for some and villains for others, but my message had been conveyed as the first edition of my first book, entitled (of course) “Psychology Rather Than Power,” which showed a completely different way of training dogs based on ethology and the scientific principles of animal learning, sold out in three months. It was a victory for psychology rather than power in more than one way, as it also proved my point that showing results works better than arguing, persuading, convincing or forcing.

Petrine was indeed an amazing dog. She taught me most of the important things I know about dogs, but she also taught me about life, respect and affection. As I said before, I trained her because it was necessary, but I must confess that I never liked the training as much as the interaction. Training was definitely secondary to having a good relationship. Therefore, I always encouraged and reinforced any behavior that showed initiative, independence, and her resolving problems her own way. This was (and is) my philosophy of education for any species. I think of my job as an educator as like being a travel guide, providing my students with opportunities to develop, to learn how to deal with their environment, to stand out from the crowd and not be just a self-denigrating face, but to make of themselves whatever they choose. If my dogs found ways to circumvent the rules and succeeded (that is what I call good canine argumentation and reasoning), I would reinforce that even at my own cost. In other words: I have always reinforced sound argumentation and conclusions consistent with their premises, even though they might have gone against my wishes and, as the good sportsman, my father educated me to be, when a better opponent on a better day beats me, I accept defeat gracefully. I applied the same philosophy to the education of my son.

When Daniel was little, we traveled a lot together. I always thought traveling, experiencing other ways of thinking and having other stances on life were good antidotes to narrow-mindedness and all that comes with it. On one occasion, we arrived at a guesthouse after a long journey and Daniel, by then about 9 or 10 years old and already an experienced traveler, quickly assessed the situation.

“OK, we have only one little bed,” he said.

“Yes, so I see,” I replied, whilst removing my heavy backpack, trying not to lose the car keys or spill our cokes.

“I have 50% of your genes, and when I have kids, they’ll have 25% of your genes, right?” he asked rhetorically.

“For sure,” I said, amazed at what a kid could learn just by accompanying his daddy to talks and seminars whilst quietly drawing pictures at the back of the room.

“So if you want me to pass 25% of your silly genes to my kids, you have to take good care of me, right?” again a rhetorical question.

“Yes, absolutely,” I answered.

“OK, so I take the bed, and you sleep on the floor,” he concluded.

I slept on the floor.

Petrine, the red, female English Cocker Spaniel was indeed one of a kind. I remember one day I had decided to invite guests for dinner and prepared a roast beef to serve them. It was no mean feat considering my extremely limited culinary skills. I was in the living room surveying the table when I glanced towards the kitchen, and my eyes registered a sight that caused instant paralysis of every muscle in my body, including my jaw, which gaped open as I recollect.

Next to the kitchen table, where I had placed the fruit of my hard labor, the once-in-a-lifetime masterpiece, my roast beef, stood Petrine. That in itself is not reason enough to make me stop breathing and incite a serious and irreversible heart-attack you may think, and you’re right, but add to that Petrine holding my roast beef in her mouth and I think you will begin to understand the cause of my instant, full body paralysis. For a moment that seemed interminable, we stood there looking at one another, me, drop-jawed and paralyzed from head to toe, and Petrine with her deep brown eyes staring at me intensely, roast beef in mouth.

If I was paralyzed, Petrine certainly was not. She began to walk towards me with a swift, self-confident, elegant pace, not once averting her gaze from mine. I merely stared in disbelief at her approach with the roast beef. Without stopping, she trotted around me in a perfectly calculated circle and sat right next to my left leg, lifting her head and the roast beef towards me, her eyes still fixed on mine.

I think I took longer to react than I normally would on this type of occasion, but I managed to bend down, take hold of the dummy (read roast-beef) and give the signal “Tak” (read release). I know I managed it because I remember trying to wipe away Petrine’s teeth marks from the roast beef and placing it on a plate on the table ready to serve to my guests. I also remember that, even though my paralysis had only been momentary, my brain was still not fully functioning, as the next I heard was a barely perceptible whine from Petrine. I looked down to find her gazing up at me, wagging her tail and all lower body as cockers do. She was right, and it was good of her to remind me. I was failing in my duties. “Free,” I said, and, as swiftly, as elegantly and as self-confidently as she had brought the roast beef to me, she went off to perform some other of her daily chores. It had all been just another episode among the many life presents us with. No more, no less— or so it seemed to her.

It was only once the guests had gone, the kitchen tidy and Daniel in bed that, sitting on my porch and enjoying a well-deserved glass of Portuguese “vinho verde,” I cast my mind back to the Petrine episode. What had been going on?

As I told you, my philosophy of education encourages determination and reasoning, and Petrine was good at that. She realized that she had been caught in the act. She had several options: one, to drop the roast beef and show submissive behavior (active and/or passive), which would have been accompanied by a “Phooey” from me, an ugly face and a very assertive tone of voice; two, to scoff as much of the roast beef as she could before I caught her, which wouldn’t have taken long considering I was no more than 6 meters (20 feet) away; three, to run with the roast beef, which she could have done, but I would inevitably have caught up with her. And, of course, she also had the option that she chose, which is not one I would have thought of myself. Why did she choose that option? All things considered, I believe it was the best option open to her, but what went through her head when she chose to do so, I would pay a handsome fee to know for sure.

None of my (attempted) scientific explanations succeeds in convincing me fully. Having been caught would produce the “phooey” and ugly face, she knew perfectly well. Being the self-confident individual she was, I have no doubt she hated any “phooey.” That I could see clearly from her expression on the few occasions, I had had to use it. She had been brought up to think for herself, to be imaginative and creative, and to believe in herself, not to be a pitiful dog waiting for her master’s voice before daring to blink.

If Petrine had rejected “phooey” as an unacceptable means of solving the conundrum, the only way to come out of it without losing face was to do what she did. She actually controlled the situation. If it is true that I could trigger her retrieving behavior (and that, combined with searching, was our best game in the whole wide world), by just assuming any position remotely resembling the game, so too could she trigger my behavior, my part in the game. That, she did indeed. She showed me a perfect retrieve, and put me in my role in the game. “Your line, now,” she said to me, clearly and emphatically without even the need of words. Like an experienced actor playing a Shakespearian part, I reacted promptly to my cue.

If a behavior repeated often with fairly predictable consequences creates moods (Pavlovian conditioning) in all of us, independently of species, which seems to be the case, I have no doubt that she associated the retrieve game with the most pleasure she could have in life. When in trouble, we have a tendency to perform behaviors that previously have brought us success, pleasure. This is a reassuring procedure, the basis even for stereotyped behaviors according to some. It is an organism’s attempt to re-establish emotional (neurophysiologic) homeostasis. If this is the case, Petrine’s solution was a good one, an intelligent one (as we would say of ourselves) and entirely compatible with our body of knowledge. It may seem improbable at first, but it becomes more reasonable the more we think about it.

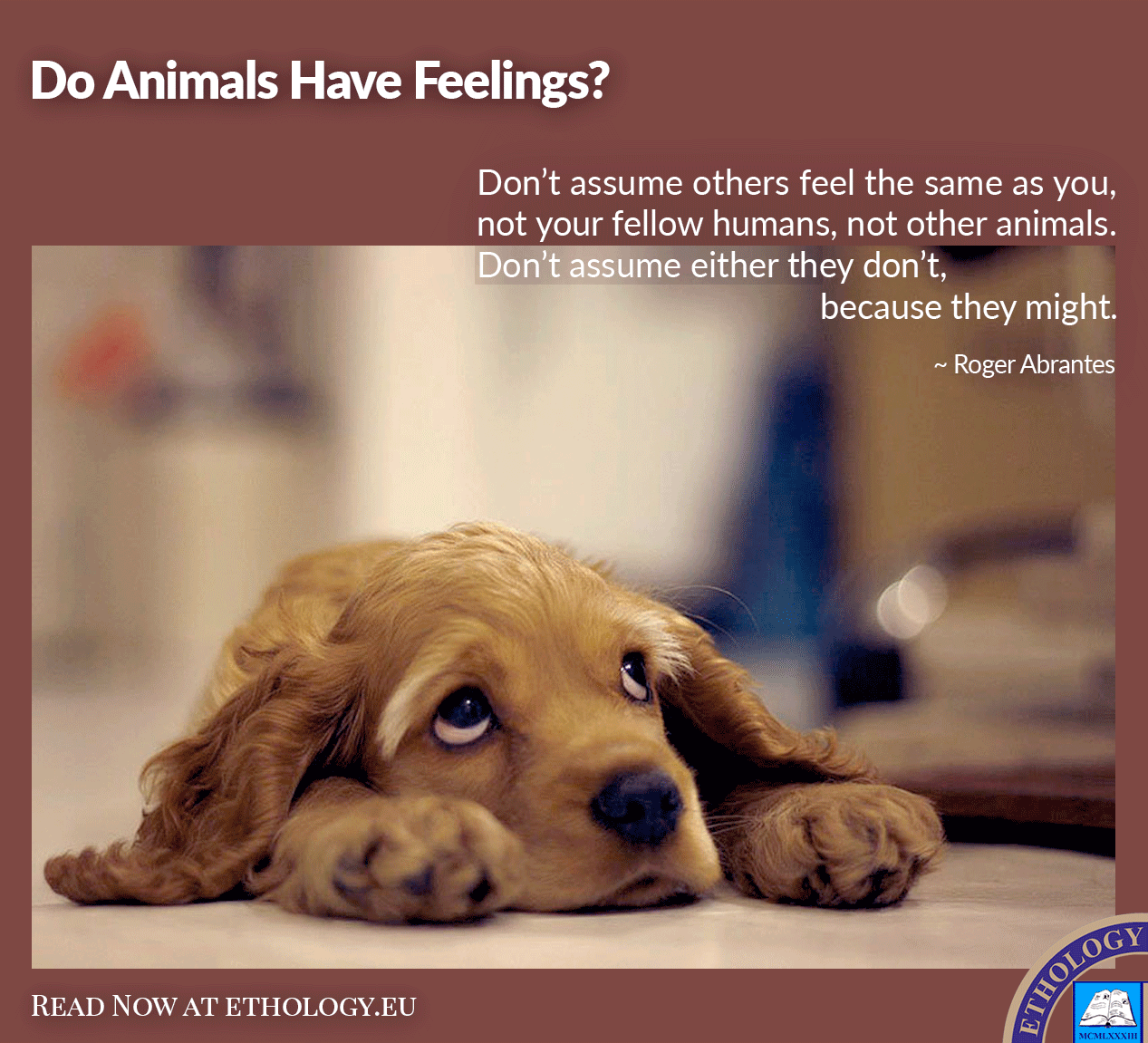

Some of you will still think I am anthropomorphizing, and you have every right to do so. Pre-Petrine era, I would have thought the same. I would never have conceived of such an explanation. However, post-Petrine, a little dog that helped me discover many facets of life on Earth, I’m no longer so sure of the boundaries of anthropomorphism. Are intelligence, reasoning and self-respect only human features? In my opinion, as an evolutionary biologist, it is unlikely. Maybe language is misleading us once again. As Carl Sagan wrote, “Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.” After all, why should “we” be so radically different from “them”?

Whilst I wouldn’t dare to rely on the unobservable self-respect on a scientific study, I wouldn’t dare either not to rely on it at a personal level on any one-on-one relationship independently of species involved. Unobservable and un-measurable, it may be, yet it remains for me a solid guideline reminding me that I am but one among many.

Life is great!