Superstitious behavior is behavior we erroneously associate with particular results. Animals create superstitions as we do. If by accident a particular stimulus and consequence occur a number of times temporarily close to one another, we tend to believe that the former caused the latter. Both reinforcing and inhibiting consequences may create superstitious behavior. In the first case, we do something because we believe it will increase the odds of achieving the desired result (we do it for good luck). In the second case, we do not do something because we do not want something else to happen (it gives bad luck).

In 1948, B.F. Skinner recorded the superstitious behavior of pigeons making turns in their cages and swinging their heads in a pendulum motion. The pigeons displayed these behaviors attempting to get the food dispensers to release food. They believed their actions were connected with the release of food, which was not true because the dispensers were automatically programmed to dispense food at set intervals.

Timberlake and Lucas concluded in 1985 “[…] that superstitious behavior under periodic delivery of food probably develops from components of species-typical patterns of appetitive behavior related to feeding. These patterns are elicited by a combination of frequent food presentations and the supporting stimuli present in the environment.”

We should be very careful when reinforcing any desirable behavior the animal we train shows us. If the reinforcement happens to coincide with other more or less accidental stimuli, we may be creating superstitious behavior. We may create superstitious behavior with any reinforcement, but probably food is the most liable to do it.

The same goes for inhibitors.1 We should always bear in mind that we never reinforce or inhibit an individual but rather a behavior.2

This can be superstitious behavior: the dog believes that if it barks long enough at the door, someone will open it because it has happened before. Many CHAP (Canine Home Alone Problems) are not even remotely connected with anxiety as many dog owners erroneously presume.

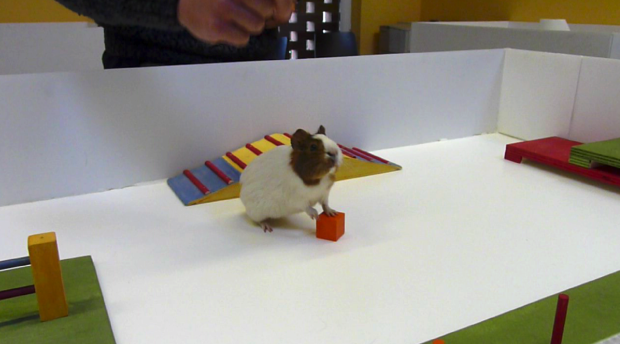

In one of our Guinea Pig camps, we saw some Guinea pigs displaying superstitious behavior. One of them would place a paw on the tin containing the target scent and would swing its head repeatedly in the direction of the trainer. The piggy created this superstition because the trainer presented the reinforcers (“dygtig” and food) when it swung its head and not when it placed the paw on the tin right after sniffing the target scent. It did not take many repetitions before the animal had created an erroneous association. Another piggy would walk over the tin if it didn’t get a reinforcer right away.

Superstitious behavior is extremely resistant to extinction. Skinner found out that some pigeons would display the same behavior up to 10,000 times without reinforcement. Displaying a behavior expecting a reinforcer, and receiving none, increases persistence. It’s like we (as well as other animals) feel that if we continue long enough the reinforcement will happen sooner or later.

As always, being an evolutionary biologist, the first question that comes to my mind is, “what conditions would favor the propagation of superstitious behavior?” Making correct associations between events confers a substantial advantage in the struggle for survival. That is what understanding (or adapting to) one’s environment means. The benefits of getting one association right outweigh the costs of making several wrong associations so much that natural selection favors those who tend to make associations rather than those who do not—and that’s why superstitious behavior is highly resilient to extinction.

________

1“Inhibitors” were earlier called “punishers.” I coined the new term in “The 20 Principles All Animal Trainers Must Know.“

2 In Abrantes 2013 and 2016.

References

Abrantes, R. (2013) The 20 Principles That All Animal Trainers Must Know. Wakan Tanka Publishers.

Abrantes, R. (2016) Animal Training My Way, Wakan Tanka Publishers.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Superstition in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 168-172.

Timberlake, W and Lucas G. A. (1985). The basis of superstitious behavior: chance contingency, stimulus substitution, or appetitive behavior? J Exp Anal Behav. 1985 Nov; 44(3): 279–299.

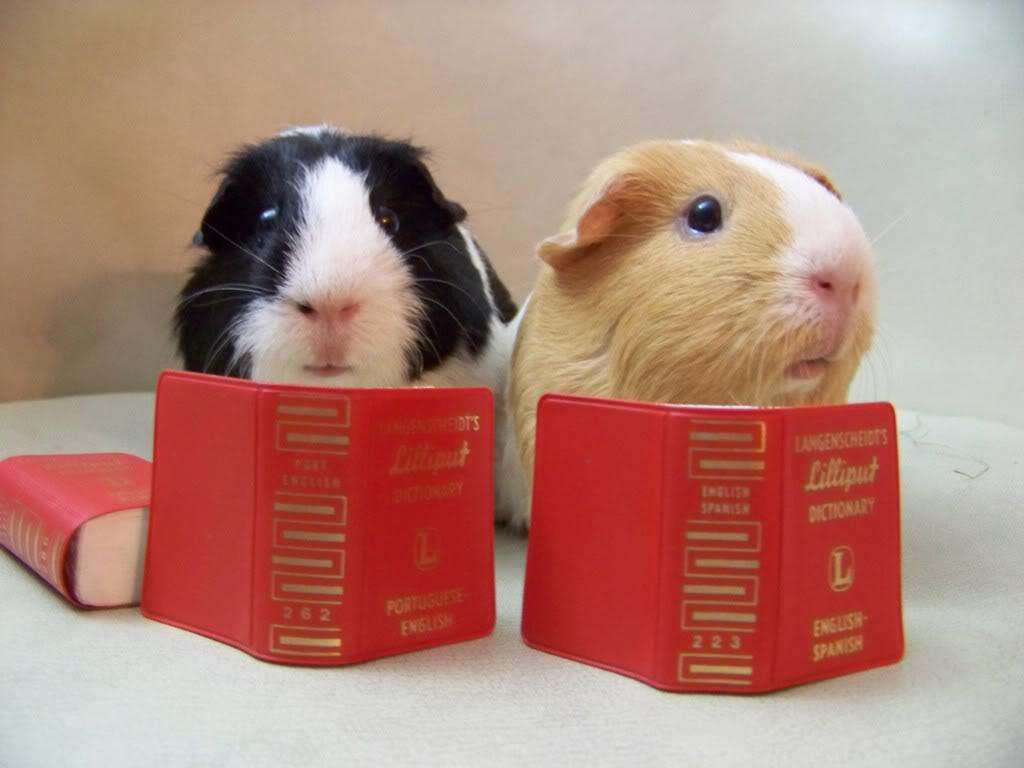

Featured image: Superstitious behavior is easy to create and extremely difficult to extinguish (photo from galleryhip.com).