The magic words ‘yes’ and ‘no‘

‘Yes’ and ‘no’ are two words used for expressing affirmatives and negatives. The words ‘yes’ and ‘no’ are difficult to classify under one of the eight conventional parts of speech. They are not interjections (they do not express emotion or calls for attention). Linguists, sometimes, classify them as sentence words or grammatical particles.

Modern English has two words for affirmatives and negatives, but early-English had four words: yes, yea, no, and nay.

If you’re a native English speaker, you know what yes and no mean, and you have no problem using these words, from a linguistic point of view. You might have a problem using the word no from a psychological point of view, but that’s an entirely different story.

If you are a native English speaker and have never ventured into learning other languages, you probably believe there is no problem in answering any question with yes or no. After all, most things either are or are not, are either true or false, right? I’m afraid I’m going to disappoint you by demonstrating that you are wrong.

Even though some languages have similar words for yes and no, we do not use them to answer questions. For example, in Portuguese, Finnish and Welsh, you rarely reply to a question with yes and no. Portuguese: “Estás bem?” (Are you OK?) “Estou” (I am). Finnish: “Onko sinulla nälkä?” (Are you hungry?) “On” (I am). Welsh: “Ydy Ffred yn dod?” (Is Ffred coming?) “Ydy” (He is coming).

In Scandinavian languages, French and German (amongst others), you answer questions with yes and no. However, you have two different ways of saying yes depending on whether the question is an affirmative response to a positively-phrased question or an affirmative response to a negatively-phrased question. In Danish and Swedish, you say (ja, jo, nej), in Norwegian (ja, jo, nei), in French (oui, si, non), and in German (ja, doch, nein).

So far so good, but if you venture into the Asian languages, it gets far more complicated. Some Asian languages don’t have words for yes and no. In Japanese, the words はい (hai) and いいえ (iie) do not imply yes and no, but agreement or disagreement with the statement of the question, i.e. “agree.” or “disagree.” はい can also mean “I understand what you’re saying.” The same in Thai: ใช่ (chai) and ไม่ใช่ (maichai) indicate “correct,” “not-correct.” In Thai, you can’t answer the question “คุณหิวข้าวไหม” (Are you hungry?) with “ใช่” (correct). It doesn’t make sense, for what is it that you are confirming to be correct? The right answers are “หิว” (hungry) or “ไม่หิว” (not hungry). In all Chinese dialects, yes-no questions assume the form “A or not-A” and you answer echoing one of the statements (A or not-A). In Mandarin, the closest equivalents to yes and no are 是 (shì) “be” and 不是 (búshì) “to not be.”

Latin has no single words for yes and no. The vocative case and adverbs do it, instead. The Romans used ita or ita vero (thus, indeed) for the affirmative, and for the negative, they used adverbs such as minime, (in the least degree). Another common way to answer questions in Latin was to repeat the verb like in Portuguese, Castellano and Catalan (e.g. est or non est). We can also use adverbs: ita (so), etiam (even so), sane quidem (indeed, indeed), certe (certainly), recte dicis (you say rightly) or nullo modo (by no means), minime (in the least degree), haud (not at all!), non quidem (indeed not).

In computer language, yes and no appear as a succession of “A or B” conditions. If condition A is true, then action X. A computer’s CPU only needs to recognize two states for us to instruct it to perform complicated operations: on or off, yes or no, one or zero.

The theories of quantum computation suggest that every physical object, even the universe, is, in some sense, a quantum computer. The cosmos itself appears to be composed of yes and no. Professor Seth Lloyd writes: “[…] everything in the universe is made of bits. Not chunks of stuff, but chunks of information—ones and zeros. […] Atoms and electrons are bits. Machine language is the laws of physics. The universe is a quantum computer.”

The way computers use yes and no is the closest to our customary use of these terms. ‘Yes’ means “continue what you are doing right now.” ‘No’ means “stop what you are doing right now.” That is the implied meaning of yes and no in the majority of the sentences. “Are you hungry?” The answer “yes” would result in you getting food and “no” in the opposite. “Shall I turn right? ” followed by a ‘yes’ would make me continue with what I intended to do and if followed by a ‘no,’ would make me stop doing it. A ‘yes’ in response to “Did you buy rice, today?” would prompt me to continue doing whatever I might be doing and a ‘no’ would lead me to interrupt my errand to go and buy some rice. There are many other examples, but in general yes prompts or encourages a continuation, and no does the opposite. There is nothing particularly positive or negative in either. Both are valuable bits of information that we can transform into behavior to our benefit. Both save energy, the most precious resource for all living organisms.

Two peculiar aspects of ‘yes’ and ‘no’

As we have seen, some languages don’t have words for ‘yes’ and ‘no.’ That is a cultural phenomenon. For example, in Japan and Thailand, it is bad manners to be direct. Japanese and Thai people consider ambiguity to be a beautiful aspect of their language. The objective in courtesy is to convey the true meaning between the lines. The way one delivers a message should be as unclear as possible, especially when criticizing someone or rejecting an invitation. This linguistic feature is probably related to the sense of self-respect and honor so pronounced in both cultures, i.e. one doesn’t want to hurt other people’s feelings or lose face.

For example, I can’t say to a Thai employee that arrives late to work, “Arriving late is not acceptable. Please, rectify this in the future.” If I do, I won’t have an employee coming to work at all the next day or maybe ever again. I’d have to say, “If we had employees that arrived late, we would have to ask them to come at the right time, don’t you think?” That would have the desired effect. If you invite a Japanese to an event that he or she is not the least interested in, they will answer “I want to come, but unfortunately, it is impossible on that day.” That would suffice for me to understand that they are not interested without making me lose face. Suggesting another day (and missing the point) is considered impolite.

Thais use ครับ (khrap, by men), ค่ะ (kha, by women) and the Japanese use はい (hai) to show that they are listening to you because it is impolite for them to let you talk for any length of time without their acknowledgment. However, it does not mean they agree with what you are saying, they will comply, or that they even understand you.

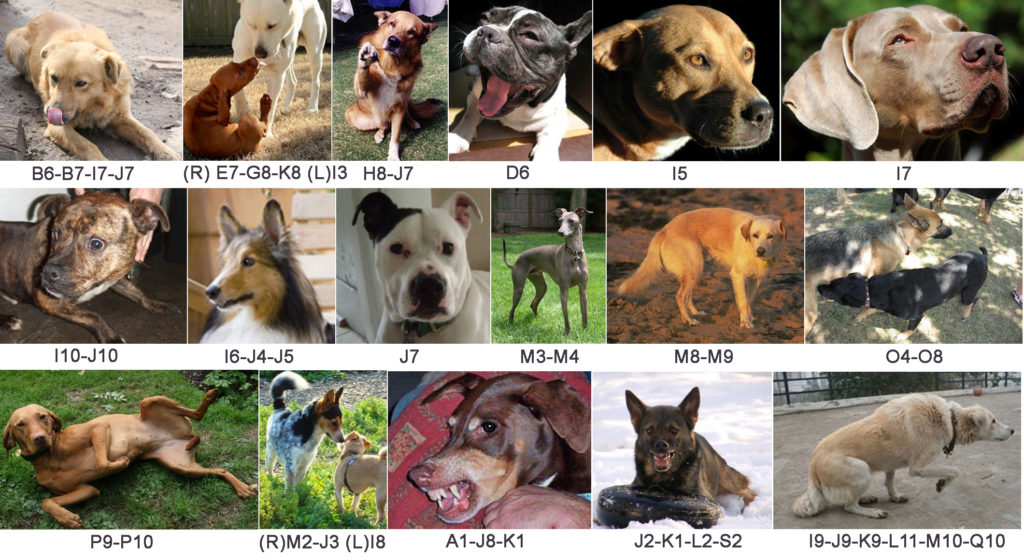

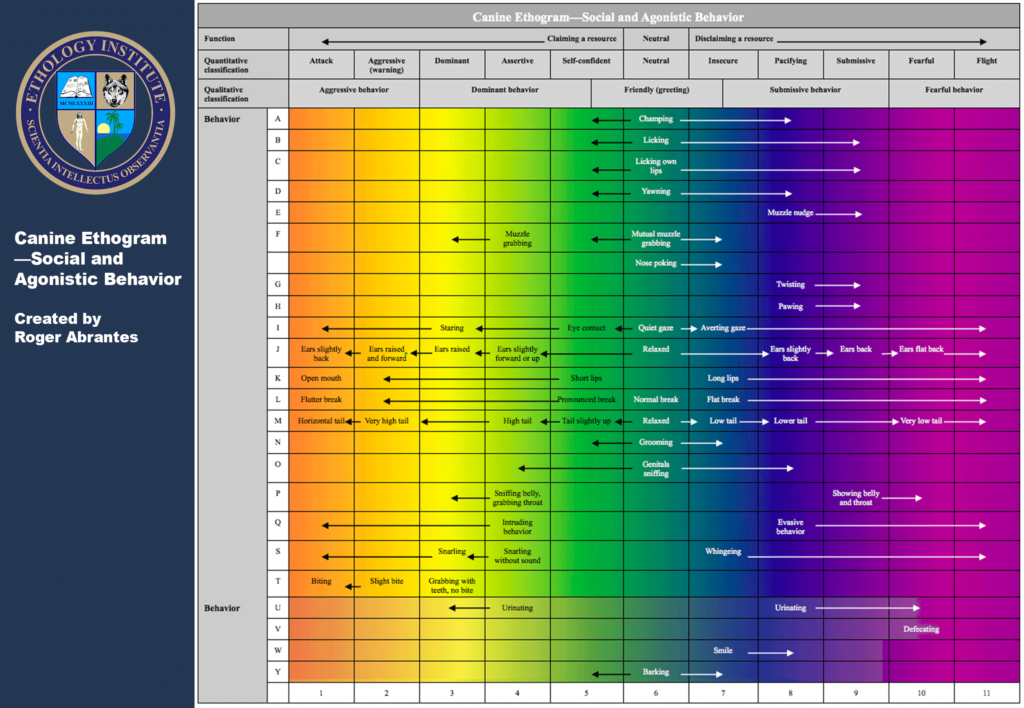

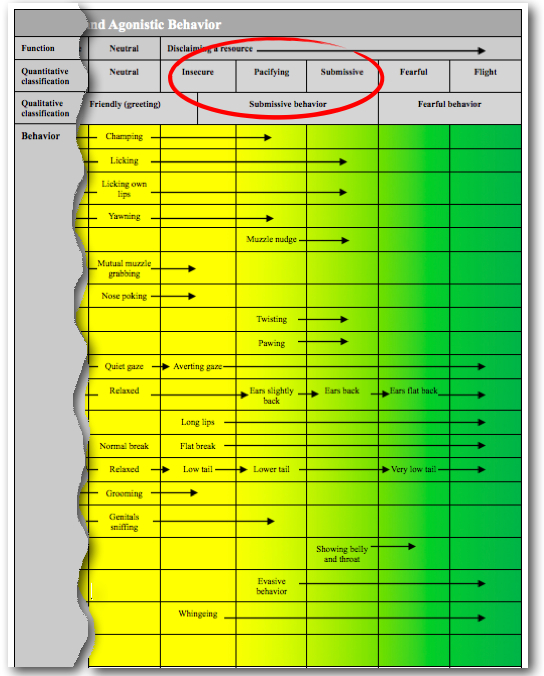

Regarding animal training, a signal is “everything that intentionally changes the behavior of the receiver.” A command is “a signal that intentionally changes the behavior of the receiver in a specific way with no variations or only minor variations.” The words ‘yes’ and ‘no’ are probably the closest we come to commands. ‘Yes’ means continue and ‘no’ means stop and, as to most behaviors, there are few possible variations in continuing or stopping, if any).

Is ‘no’ a bad word?

‘No’ is not a bad word. On the contrary, it is a very useful word. It conveys information in a precise and efficient way. To get ‘no’ as an answer is as important as getting a ‘yes.’ Both save us energy and lead us to our goal. Personally, I like the words yes and no equally, and I wished people would learn to use them properly and more often.

The other day, I went into a store at a busy hour, and I didn’t have the time or the patience to wait. I said to one employee: “Excuse me, I have a question that you can answer quickly with a yes or no. Do you have a Time Capsule 2TB?”

“I have one, but it’s reserved for a customer,” he answered.

“What does that mean? Is he coming to pick it up or not?” I asked again.

“Yes, he is.” He answered.

“Well, then that’s a no, right?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said.

Why couldn’t he just have said no the first time? It would have saved us all time: me, the other customers in the line, and not least himself.

Another example:

United Airlines desk at the gate boarding to ORD: I approach and ask: “Do you have an empty seat on this flight?”

The United operator answers me: “That depends on your ticket, sir.”

“No, it doesn’t,” I reply, “whether or not you have empty seats does not depend on my ticket, It depends on whether all the seats will have butts on or not.”

A colleague of hers smiles and checks it. “Sorry, sir, this flight is fully booked. I have one seat on the next flight, but… it’s business class.”

“No ‘but.’ You can put a comma or an ‘and’ in there,” I say. It blows my mind. A seat is a seat, and that’s what I requested. A seat is not less of a seat because it is a business class seat.

“Excuse me, sir?” she replies with a smile, plainly not understanding my comment based on linguistics/logic.

“Never mind. Here’s my frequent flyer card. I have an e-ticket for the 7.13 pm flight. Please, upgrade it with my miles. Thank you.” I say smilingly, in an attempt to reinforce her behavior for having been able to think clearly (yes/no) for two seconds and for checking the availability on the next flight.

“Yes, sir.” Finally a short and precise answer!

Why couldn’t they have answered first ‘no’ and then ‘yes’ until they got the next bit of information if I had any to give them? It would have saved me (and them) time and energy. If the lack of words for ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in Asian languages is frustrating for the Western communicator, the refusal to use them, or their incorrect usage in languages where they exist and are well defined, is exasperating.

Why don’t some people like the word ‘no’?

Cultural differences apart, some people don’t like the word ‘no’ for the same reason that some dogs don’t like it: they associate ‘no’ with aversives. Parents are just as bad as dog owners in distinguishing between signals and inhibitors, and they make identical mistakes, which will later create problems to their children.

Of course, parents have to yell ‘no’ if the toddler is about to stick his fingers in the wall outlet (plug socket). There’s nothing wrong with that. What is incorrect, and creates the aversive respondent association with ‘no’, is the constant repetition without a reinforcer when the behavior stops. The toddler only learns that, sometimes, parents go berserk, and she has no idea why or how to avoid it. The toddler becomes so sensitive to the word ‘no’ that later, like many others, he or she would rather live with regret than to risk hearing a ‘no.’ This conditioning can also happen subsequently, in adult life, to which abusive parents, enraged spouses, and tyrannical bosses all contribute.

An elementary mistake, committed by both parents and dog owners, adds to the aversive connotation of ‘no.’ If we have to use inhibitors, we should never (ever) inhibit the individual, only the behavior. Inhibiting the individual may create traumas, a lack of self-confidence, the feeling of rejection, etc. Inhibiting the individual rather than the behavior can even produce aggressive behavior instead of decreasing the expected behavior.

The reason some people don’t like ‘no’ has nothing to do with the word or the message conveyed, but with the aversives to which it was (respondently) conditioned. Changing that goes beyond the scope of biology, animal behavior, and linguistics, and pertains to the realm of psychology.

Still, there’s nothing wrong with the word ‘no’ and particularly not with the message it conveys. There is something wrong with abusive parents, enraged spouses, tyrannical bosses and ignorant people (all potentially abusive animal owners). To forbid the word ‘no’ or to replace it with another, e.g. ‘stop,’ does not resolve the problem. The only thing that does solve the problem is to educate people, to teach them to respect others independently of species, race, and sex.