The question has popped up several times in discussions on social media, with one faction adamant that wolves and dogs have nothing or very little to do with one another. As a result, we should not make comparisons between them.

As to how similar and different wolves and dogs are, I gave a lecture, “Wolf and Dog— A Comparative Study,” for the first time at the UNAM, Cuautitlán, Mexico, on May 2, 2017, covering the topic from (of course) a strictly scientific point of view. Having been studying wolves, dogs, and related canids for almost all of my professional career, I’ve collected plenty of evidence to pass judgment on the question.

It’s essential for us, as true behavioral sciences students, to stick to facts and sound argumentation. Therefore, I will give you here some points to help you evaluate the debate about wolves and dogs that we’ve seen on the internet, one dominated by hidden political agendas, emotional outbursts, and old wives’ tales. These facts will help you conduct a debate based on the currently available evidence and form an informed opinion on the topic.

Let me remind you that the term ‘compare’ in science refers to the discovery of similarities and differences. Both are equally fascinating and may supply us with valuable knowledge.

The following is only a short sample of the many more comparative facts we have. Please see the reference list.

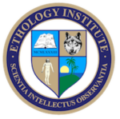

● The dog family, Canidae, diverged from other carnivore families 50 to 60 million years ago. The family, comprising 34 extant species, shows a wide range of chromosome morphologies. The diploid chromosome number varies from 2n=36 (mainly metacentric autosomes) in the red fox, Vulpes vulpes, to 2n:78 (with all autosomes being acrocentric) in the domestic dog and various wolf-like canids such as the gray wolf, Canis lupus lupus. The chromosomal rearrangements in the different species help us deduce the group’s phylogenetic history (Wayne et al. 1987).

● Mitochondrial DNA sequences also reveal the Canidae’s evolution and the origins of the domestic dog (Wayne 1993). The results show that the domestic dog, Canis lupus familiaris is an extremely close relative to the gray wolf, with as little as 0.2% variation in mitochondrial DNA sequence between the two. That contrasts with the 4% variation in mitochondrial sequences between gray wolves and their nearest wild relative, the coyote, Canis latrans.

● Whole genome sequencing indicates that the dog (Canis lupus familiaris), the gray wolf (Canis lupus lupus), and the extinct Taymyr wolf diverged at around the same time 27,000–40,000 years ago (Callaway, 2015).

● Wolves and dogs differ by 0.2 to one percent, using the wolf-coyote time scale. That suggests they parted company about 135,000 years ago (based on samples from 140 dogs of 67 breeds and 162 wolves; see Robert Wayne, UCLA in Budiansky, S. 1999. The Atlantic Monthly; July 1999; The Truth About Dogs; Volume 284, No. 1; page 39-53).

● Canis lupus familiaris: 88% of its behavior is equal to the behavior of the Canis lupus lupus or slightly modified (Zimen, 1992; Feddersen-Petersen, 2004).

● Domestication seems to have caused a reduction in cooperative tendencies in dogs, mainly because of the significantly reduced cooperative breeding and hunting in dogs compared to wolves (Boitani & Ciucci, 1995; Coppinger & Coppinger, 2001; Kubinyi et al., 2007; Miklósi, 2007a; Range et al., 2009; Brauer et al., 2013).

● Unlike wolves, free-ranging dogs have a primarily promiscuous mating system (Daniels, 1983; Ghosh et al., 1984; Boitani et al., 1995; Pal et al., 1999; Pal, 2003). They rarely form monogamous pairs (for exceptions, see Gipson, 1983; Pal, 2005). Group members, other than their mother, rarely feed puppies (Macdonald & Carr, 1995; Boitani et al., 1995; Lord et al., 2013).

● Based on recordings of the social behavior of approximately 200 canines, including ritualized and non-ritualized forms of agonistic behaviors, play, and other affiliative behaviors, Feddersen-Petersen (2007) suggested that—contrasting to wolves—dogs have difficulties in cooperating even in a simple manner of just doing things together.

● Dog puppies show higher levels of aggressive behavior than wolf cubs (Feddersen-Petersen, 1991).

● In general, the ranking order (hierarchy) is a lot steeper in dogs than in wolves, resulting in a considerable social distance between the high-ranking animal(s) and the rest of the group (Feddersen-Petersen 1991).

In dogs, agonistic interactions often reach high aggression levels because dogs lack most strategies that wolves commonly use to solve conflicts, such as pacifying and inhibiting their opponents (Feddersen-Petersen 1991).

● Studies of free-ranging dogs assessed hierarchies using the same behavioral patterns described for wolves, i.e., submissive gestures, dominance displays, and aggressive behavior (Cafazzo et al., 2010).

● As in wolves, submissive gestures had a higher directional frequency within dyads (van Hoof & Wensing, 1987; Cafazzo et al., 2010).

● Results of studies suggest that the structure of the dog packs was relatively similar to that of wolf family packs, in which the ranking order is based on age, and males tend to dominate females within a given age class (van Hoof & Wensing, 1987; Mech, 1999; Packard, 2003).

● In small wolf family packs, both the breeding male and the breeding female share leadership (Mech, 2000).

● However, in large wolf family packs containing multiple sexually mature individuals, the higher-ranking breeders usually lead movements during 60%–90% of travel time (Peterson et al., 2002), meaning that in a non-negligible minority of cases, subordinate offspring can also provide leadership.

● Leadership was shared among group members in the studied dog packs, although not equally (Bonanni et al., 2010). Although every dog of at least one year of age could sometimes behave as a leader, each pack contained a limited number of ‘habitual leaders’ (i.e., individuals who behaved more frequently as leaders than they behaved as followers).

● Old and high-ranking individuals mainly provide leadership in the studied population’s free-ranging dogs (note that age and rank are positively correlated). This pattern seems to be relatively similar to that found in wolf family packs, in which parents lead activities (Mech, 2000; Peterson et al., 2002).

● In dogs, but not wolves, high-ranking animals show more aggression than lower-ranking ones about monopolizing the food (Ritter et al., 2012).

● Wolves are more tolerant than dogs during feeding competitions. Dogs develop a ‘steeper’ hierarchy that inhibits aggression directed towards higher-ranking group members (Ritter et al., 2012).

● Conclusion: Wolf and dog are quite similar in anatomy and physiology as to behavior, in some aspects more than others. See also the video “A Dog Is Not a Wolf—Is It?”

Phylogeny of canid species: the wolf-like clade. The phylogenetic tree is based on 15 kb of exon and intron sequence. The tree shown was constructed using maximum parsimony as the optimality criterion and is the single most parsimonious tree. Species names are represented with corresponding illustrations. Divergence time, in millions of years (Myr), is indicated for three nodes (Figure from Nicole Stange-Thomann, adapted by Roger Abrantes).

_____________

Note: For comparison, humans (Homo sapiens) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) last shared a common ancestor ∼5-7 million years ago (Mya). The two species differ in DNA by ~4%. (Chen and Li 2001; Brunet et al. 2002; Varki, A., & Altheide, T. K. 2005). The complete mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) molecules of Homo and the common chimpanzee were sequenced. The nucleotide difference between the entire human and chimpanzee sequences is 8.9%. The difference between the control regions of the two sequences is 13.9% and 8.5% between the remaining portions of the sequences (Arnason et al. 1996).

_____________

References

Abrantes, R. (1997). The Evolution of Canine Social Behavior. Wakan Tanka Publishers. ISBN: 0-9660484-1-5.

Arnason U, Xu X, Gullberg A. (1996). Comparison between the complete mitochondrial DNA sequences of Homo and the common chimpanzee based on nonchimeric sequences. J Mol Evol. 1996 Feb;42(2):145-52. doi: 10.1007/BF02198840. PMID: 8919866.

Boitani L. (1983). Wolf and dog competition in Italy. Acta Zoologica Fennica. 1983;174:259-264.

Boitani, L. & Ciucci, P. (1995) Comparative social ecology of feral dogs and wolves, Ethology Ecology & Evolution, 7:1, 49-72, DOI: 10.1080/08927014.1995.9522969.

Boitani L., Ciucci P., Ortolani A. (2007). Behaviour and social ecology of free-ranging dogs. In: Jensen P., ed. The behavioural biology of dogs. Wallingford, UK: CAB International; 2007:147-165.

Bonanni R. (2008). Cooperation, leadership and numerical assessment of opponents in conflicts between groups of feral dogs. Italy: Ph.D. thesis, University of Parma; 2008.

Brunet, M., Guy, F., Pilbeam, D., Mackaye, H.T., Likius, A., Ahounta, D., Beauvilain, A., Blondel, C., Bocherens, H., Boisserie, J.R., et al. (2002). A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa. Nature 418: 145-151.

Bräuer, J., Bös, M., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2013). Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) coordinate their actions in a problem-solving task. Animal cognition, 16(2), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-012-0571

Callaway, E. (2015) Ancient wolf genome pushes back dawn of the dog. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2015.17607

Cafazzo S., Valsecchi P., Bonanni R., Natoli E. (2010). Dominance in relation to age, sex and competitive contexts in a group of free-ranging domestic dogs. Behav. Ecol. 2010;21:443-455.

Chen, F.C. and Li, W.H. (2001). Genomic divergences between humans and other hominoids and the effective population size of the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68: 444-456.

Coppinger, R. & Coppinger, L. (2001). Dogs-A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior & Evolution. Bibliovault OAI Repository, the University of Chicago Press.

Daniels, T.J. (1983). The social organization of free-ranging urban dogs. II. estrous groups and the mating system, Applied Animal Ethology, Volume 10, Issue 4, 1983, ISSN 0304-3762, https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3762(83)90185-2.

Feddersen-Petersen D. (1991). Verhaltensstörungen bei Hunden—Versuch ihrer Klassifizierung [Behavior disorders in dogs–study of their classification]. DTW. Deutsche tierarztliche Wochenschrift, 98(1), 15–19.

Feddersen-Petersen, D. (2004). Hundepsychologie. Sozialverhalten und Wesen. Emotionen und Individualität. 4. Auflage. Franckh-Kosmos. ISBN: 978-3-440-13785-7.

Feddersen-Petersen D.U. (2007) Social behaviour of dogs and related canids. In: Jensen P., ed. The behavioural biology of dogs. Wallingford, UK: CAB International; 2007:105-119.

Ghosh B., Choudhuri D.K., Pal B. (1984). Some aspects of sexual behaviour of stray dogs, Canis familiaris. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1984:13:113-127.

Gipson P.S. (1983) Evaluations of behavior of feral dogs in interior Alaska, with control implications. Vertebrate Pest Control Manag. Mater. 4th Symp. Am. Soc. Testing Mater. 1983;4:285-294.

Kubinyi, E., Virányi, Z., Miklosi, A. (2007). Comparative Social Cognition: From wolf and dog to humans. Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews. 2. 10.3819/ccbr.2008.20002.

Lindblad-Toh, K., Wade, C.M., Mikkelsen, T.S., Karlsson, E.K. (2005) Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature 438(7069):803-819. DOI: 10.1038/nature04338.

Lord K., Feinstein M., Smith B., Coppinger R. (2013). Variation in reproductive traits of members of the genus Canis with special attention to the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). Behav. Processes. 2013;92:131-142.

Macdonald D.W., Carr G.M. (1995). Variation in dog society: between resource dispersion and social flux. In: Serpell J., ed. The domestic dog: its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995:199-216.

Mech D. (1970). The Wolf: The Ecology and Behaviour of an Endangered Species. Garden City, NY: Natural History Press.

Mech L.D. (1999). Alpha status, dominance, and division of labor in wolf packs. Can. J. Zool. 1999;77:1196-1203.

Mech L.D. (2000). Leadership in wolf, Canis lupus, packs. Can. Field-Natural .2000;114:259-263.

Mech L. D., Boitani L. (2003). Wolf social ecology, in Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation, eds Mech L. D., Boitani L. (Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press; ), 1–35.

Miklosi, A. (2008). Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. 1-304. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199295852.001.0001.

Packard J.M. (2003). Wolf behavior: reproductive, social and intelligent. In: Mech L.D., Boitani L., eds. Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation. Chicago, IL, and London: University of Chicago Press; 2003:35-65.

Pal, S.K., Ghosh B., Roy S. (1998). Agonistic behaviour of free-ranging dogs (Canis familiaris) in relation to season, sex and age. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998;59:331-348.

Pal, S.K., Ghosh B., Roy S. (1999). Inter- and intrasexual behaviour of free-ranging dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999;62:267-278.

Pal, S.K. (2001). Population ecology of free-ranging urban dogs in West Bengal, India. Acta Theriol. 2001;46:69-78.

Pal, S.K. (2003). Reproductive behaviour of free-ranging rural dogs in West Bengal, India. Acta Theriol. 2003;48:271-281.

Pal, S.K. (2005). Parental care in free-ranging dogs, Canis familiaris. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005;90:31-47.

Peterson, O., Jacobs A.K., Drummer I.D., Mech L.D., Smith D.W. (2002). Leadership behavior in relation to dominance and reproductive status in gray wolves, Canis lupus. Can. J. Zool. 2002:80:1405-1412.

Range F., Horn L., Bugnyar T., Gajdon G. K., Huber L. (2009). Social attention in keas, dogs, and human children. Anim. Cogn. 12, 181–192. 10.1007/s10071-008-0181-0.

Range, F., & Virányi, Z. (2015). Tracking the evolutionary origins of dog-human cooperation: the “Canine Cooperation Hypothesis.” Frontiers in psychology, 5, 1582. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01582.

Ritter, C., Viranyi, Z., Range, F., (2012). Who is more tolerant? Cofeeding in pairs of pack-living dogs (Canis familiaris) and wolves (Canis lupus). Third International Canine Science Forum.

van Hoof J.A.R.A.M., Wensing J.A.B. (1987). Dominance and its behavioural measure in a captive wolf pack. In: Frank H.W., ed. Man and wolf. Dordrecht, Olanda (Netherlands): Junk Publishers; 1987:219-252.

Varki, A., & Altheide, T. K. (2005). Comparing the human and chimpanzee genomes: Searching for needles in a haystack. Comparing the Human and Chimpanzee Genomes: Searching for Needles in a Haystack; genome.cshlp.org. https://genome.cshlp.org/content/15/12/1746.full#ref-10.

Vilà, C., Savolainen, P., Maldonado, J. E., Amorim, I. R., Rice, J. E., Honeycutt, R. L., Crandall, K. A., Lundeberg, J., & Wayne, R. K. (1997). Multiple and Ancient Origins of the Domestic Dog. Science, 276(5319), 1687–1689. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2892656

Wayne R. K. (1993). Molecular evolution of the dog family. Trends in genetics : TIG, 9(6), 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9525(93)90122-x

Wayne, R. K., Geffen, E., Girman, D. J., Koepfli, K. P., Lau, L. M., & Marshall, C. R. (1997). Molecular Systematics of the Canidae. Systematic Biology, 46(4), 622–653. https://doi.org/10.2307/2413498.

Wayne, R. K., Nash, W. G., & O’Brien, S. J. (2008). Chromosomal evolution of the Canidae. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics 1987, Vol. 44, No. 2-3 – Karger Publishers.

Zimen, E. (1992). Der Hund – Abstammung, Verhalten, Mensch und Hund. Goldmann, 1992. ISBN-10: 3442123976.

Featured Course of the Week

Ethology Ethology studies animal behavior in its natural environment. It is one of the fundamental courses in your curriculum. A reliable knowledge of animal behavior is the basis to create a satisfying relationship with any animal we train.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00