Motivation is a term we all use, and we believe everybody understands. We think we know what it means and that others do too—but do we truly understand motivation?

Motivation is a problematic term beginning with its definition. For the present purpose, let me define motivation as what compels an animal to do what it does, as the sum of all factors (internal and external) which cause an organism to behave in a goal-seeking way. At least, now you know what I’m talking about (and what I’m not talking about).

The traditional view of motivation builds upon a single feedback principle. The brain senses a change in the animal’s internal state, which leads to a build-up of drive for the animal to perform the appropriate behavior. The drive gives rise to appetitive and consummatory behavior, including a search for suitable external stimuli. When the animal encounters these, some activity as eating or drinking takes place. That is all too oversimplified and includes terms in themselves difficult to define, e.g., drive—but it will do as a starting point.

There is not one single theory of motivation, but the general tendency is clear. Some researchers have been keen to stress that motivation aims at reducing stimulation to its lowest level. Thus, an organism seeks the behavior most likely to cause a state of no stimulation. However, recent theories of motivation picture animals trying to optimize rather than minimize (or maximize) stimulation. These theories account for exploratory behavior, variety-seeking behavior, and curiosity.

The concept of motivation applies to communication patterns. There is no behavior without motivation, except for strict Pavlovian reflexes, and even this is arguable. Motivation is decisive in the various behaviors animals use as communication means and in learning processes.

The instinct theory states that motivation depends on an organism’s biological make-up. Animals are born with specific, pre-programmed innate knowledge about how to survive and reproduce. Darwin explained the survival of an organism as resulting from the instinct for survival. The first behaviorists also recurred to instincts to explain motivation.

Ethology, including the contributions of Konrad Lorenz, Nikolaas Tinbergen, Karl von Frisch, and Irenaus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, defined instincts as unlearned behaviors and responses. The drive reduction theory assumes that animals have needs, which motivate them to behave in specific ways. Drives are internal states of arousal, e.g., hunger and thirst, which the organism attempts at reducing. The organism seeks to reestablish homeostasis. Though no longer entirely satisfactory, the early ethologists’ approach is still helpful to understand behavior at a particular level.

Explaining behavior in terms of instincts proved unsustainable because we could always coin a new instinct to describe an unexplained behavior. Sociobiology attempted to remedy that. Evolving from the instinct theories of ethology, it added a crucial genetic component to motivation.

The theory of physiological regulation explains motivation in terms of some complex processes of the nervous system.

The consensus these days is that though we know more or less what motivation means, we cannot account exhaustively for all the factors determining it. Prudent judgment and open-mindedness seem, therefore, advisable in this matter and at this moment.

References

Breland, K. & Breland, M. (1961) The misbehavior of organisms. American Psychologist 16: 681–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040090.

Catania, A. C. (1984) Learning, 2d ed.Prentice-Hall. ISBN-10: 0135276977.

Colgan, P.W. (1989) Animal Motivation. Springer Netherlands. DOI:10.1007/978-94-009-0831-4.

Cooper JO (2007) Applied Behavior Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Pearson Education. ISBN: 978-0-13-129327-4.

Dawkins, M. (1990) From an animal’s point of view: Motivation, fitness, and animal welfare. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 13(1), 1-9. DOI:10.1017/S0140525X00077104.

Dawkins, R. (1982) The extended phenotype. W. H. Freeman. ISBN-10: 0716713586.

Freud S (2012). A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Renaissance Classics. ISBN: 9781484156803.

Hughes, B.O., Duncan, I.J.H. (1988) The notion of ethological ‘need’, models of motivation and animal welfare. Animal Behaviour, Volume 36, Issue 6, 1988, Pages 1696-1707. ISSN: 0003-3472.

Lorenz, K. (1950) The comparative method in studying innate behaviour patterns. Symposium of the Society for Experimental Biology 4: 221–68. http://klha.at/papers/1950-InnateBehavior.pdf.

Lorenz, K. (1981) The Foundations of Ethology. Springer. ISBN: 978-3-211-81623-3.

McFarland, D. J. (1989) Problems of Animal Behaviour. Longman Scientific & Technical. ISBN-10: 0582468205.

Salamone JD, Correa M (2012) The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron. 76 (3): 470–85. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.021

Tinbergen, Nikolaas (1951). The Study of Instinct. Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780198577225.

Tinbergen, N. (1963). On aims and methods of Ethology. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 20 (4): 410–433. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1963.tb01161.x.

Wilson, E.O. (1975) Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Harvard University Press. ISBN: 0-674-00089-7.

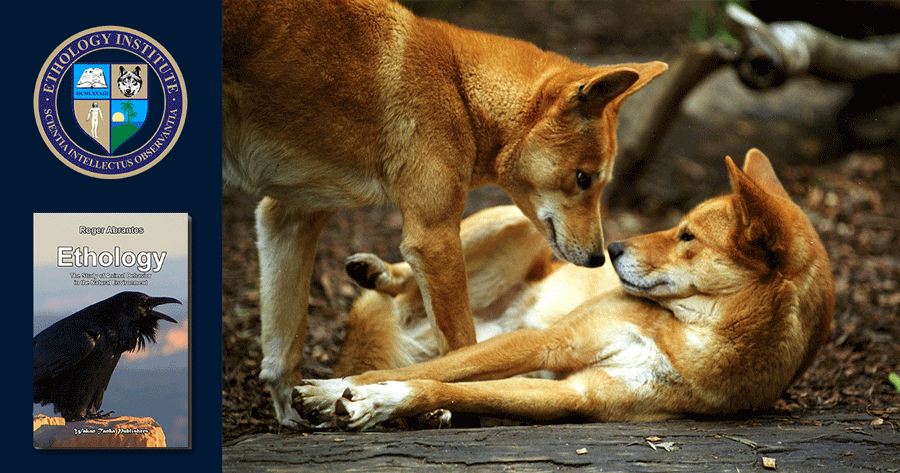

Featured image: Motivation—Where there’s a will, there’s a way (photo by unknown).

Featured Course of the Week

Ethology Ethology studies animal behavior in its natural environment. It is one of the fundamental courses in your curriculum. A reliable knowledge of animal behavior is the basis to create a satisfying relationship with any animal we train.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.