A Girl and a Wild Mustang

—or “There Are Many Right Ways to Train Animals”

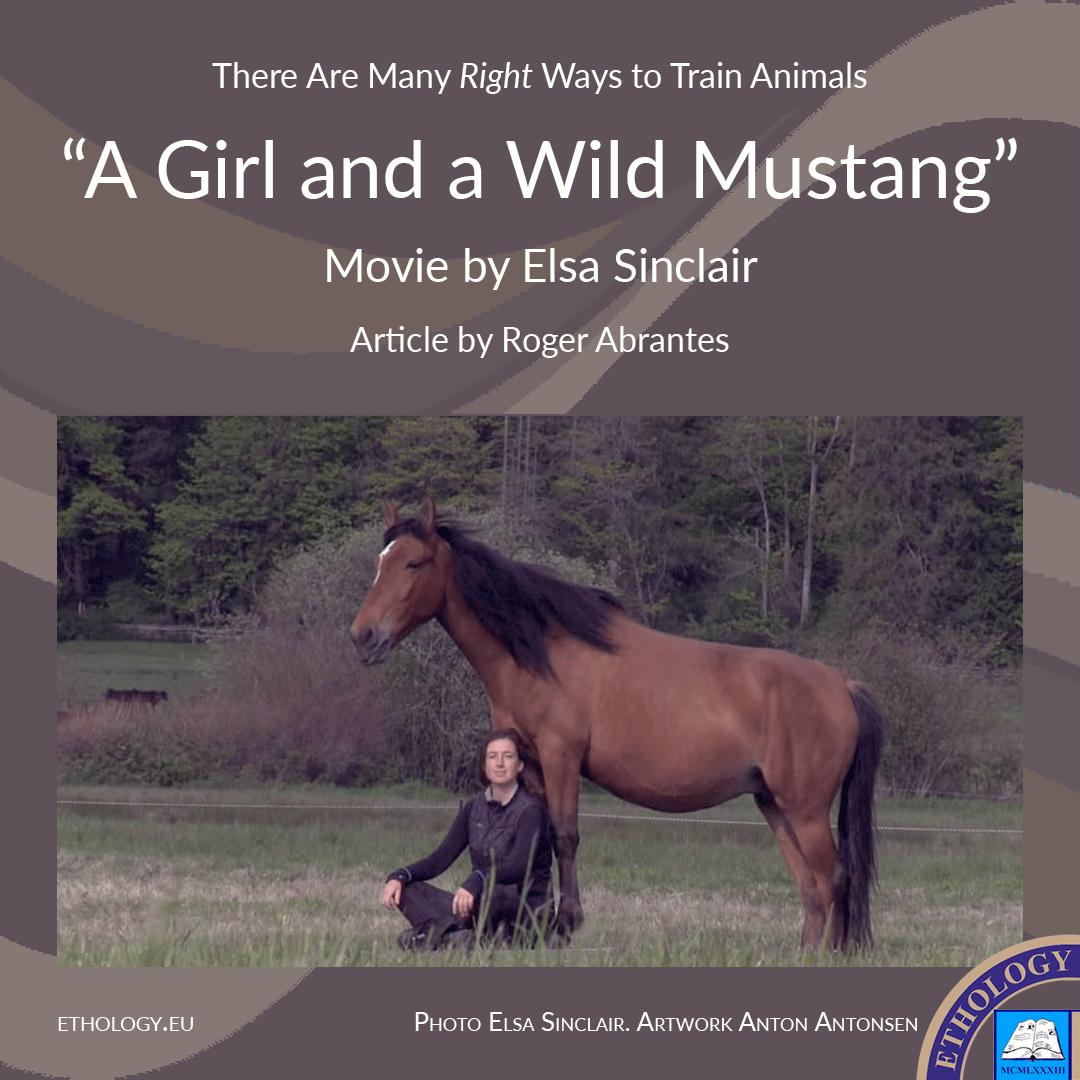

“A Girl and a Wild Mustang” by Elsa Sinclair is a beautiful documentary—and yes, I’m biased.

I’ll explain why I find it beautiful and why I’m biased in a while. See, these days a tendency prevails in claiming there’s only one right way for us to interact with our animals. If you adhere to that idea, I fear I have bad news for you. There isn’t only one way to train animals; there are many. Let’s start from the beginning.

If you know a bit about evolutionary biology, you’ll know there are countless more ways to be dead than alive. Once we are alive, there are many ways of living, depending on anatomical, physiological, and environmental constraints. Once we’re over that, we are what we are, based on genetics, epigenetics, early imprinting, education, adaptation, goals, and circumstances.

It’s no surprise we differ from one another, no two humans, dogs, horses, or jellyfish being clones of each other.

In humans, the values, morals, and ethics we acquire throughout life accentuate peculiarities. Perhaps they do also in some other species (the evolutionary biologist suspects); only we don’t know.

Like/don’t like (the Facebook syndrome, as I coined the phenomenon) expresses our normative side (emotions and values) more than their descriptive counterparts (reason and facts). They reveal the radical and inescapable subjectivism and singularity of any conscious living organism—a condition Oriental philosophies heroically attempt to elude. We judge as we find suitable and as we can. We reason, but I’ll argue that normative judgments have the better of their descriptive analogs—at least for the human species at large. Perhaps once that gave us an evolutionarily advantageous edge.

Because we act according to our norms and not de facto facts, disagreement is expectable. Compound that with a good dose of faulty logic—the standard in human reasoning—and the probability of dissent moves one notch up from expectable to inevitable.

White is the safest color for a car, yet silver is the most popular. Why? Because car buyers chose by emotion, not reason. There’s nothing wrong with that (from a logical perspective) as long as we don’t claim that (A) safety is a concern of ours, and (B) color does not matter. Why is that so? Because, although the argument is valid, it is unsound.

The validity of an argument does not depend on its premisses being true, but its soundness does. A deductive argument is sound if and only if it is both valid, and all of its premises are true. In our example above, (B) is false, and the argument is, therefore, unsound.

There are many ways to train animals, depending on our knowledge, skills, goals, and preferences. Say, we want to establish a reciprocal, beneficial relationship with our dog or horse. We may choose any method we want: reinforcers only, combining reinforcers and inhibitors, a particular lead/leash, food or no food. Different approaches can be equally good. What we cannot do—provided we want to stay rational—is to justify our actions based on values with false facts.

What science tells us, does not oblige us to adopt any one method. Science doesn’t say a particular method is unconditionally better than another. It says that under specific circumstances A rates over B and B over C with a certain probability. A may be better for speed, B for reliability, and C for individual comfort. I choose, you choose, we choose what suits each of us best. We may want to go for speed, reliability, or what feels most comfortable for us. As long as we do not deny the facts science gives us, there’s nothing wrong with any choice of ours. What is wrong (unsound argumentation, as we saw above) is to state that we choose a particular method because of its efficiency for a specific purpose despite science telling us otherwise.

For example, during my career, I have assisted many owners and their animals. Invariably, my first questions would be, “what is your goal?” and “what price are you willing to pay?” And by price, I didn’t mean bucks, dimes, and pennies, but deviating from your values if need be.

Gimmicks—leads, collars, halters, food treats—speed up training a dog or a horse. Using neither is slower, and it requires much more knowledge, skill, and empathy. Again, it depends on what you want.

Students and clients often ask me which lead I recommend or prefer. My answer is always the same. I endorse none, but I can tell you what studies (not opinions) say about the effects of the various types—and you pick one, given your goals and principles.

If you ask me, I prefer none: no leads/leashes, collars, or any gimmicks. For me, the primary in any relationship with an animal (human or not) is the connection per se. I want it to be one between two free agents: no constraints besides the inevitable of having neighbors and having to share the world with others. That’s me, and I don’t expect you to think likewise—and I wouldn’t dream of imposing my view on you.

Given, I could achieve faster and more accurate and reliable results using other methods. Denying that is out of the question for it would compromise my intellectual integrity, which I am utterly incapable of doing. Blame my genetic constitution, early upbringing, education, and fortuitous circumstances.

Therefore, I’m willing to pay the price of sticking to my philosophy of life (and being slower, less accurate, etc.)—perhaps because I find the payback worth it. As I write elsewhere, “[…] (I) enjoy the closeness, not the training, not (the) achievement, […] relating to the animal (I) face as a living organism, an equal, a creature (I) meet for a brief moment in space and time.” (Animal Training My Way, 2015).

And so, you make your choices, to which you are fully entitled, and I mine. We are equally right as long as we do not deny facts or use faulty logic in our reasoning—which takes us to “A Girl and a Wild Mustang.”

As to my preferred interaction with animals (humans too), I’d suggest you watch Elsa Sinclair’s “A Girl and a Wild Mustang.” Sinclair made her choices and proved her point. Incidentally, she also proved my case, better than I could have done it—for which I’m grateful. You must see this documentary.

Sinclair does not impose her thoughts on you, rather states her case. It’s a take it, or leave it. As I said at the start, it’s a beautiful movie, and I am biased. My most avid readers will know right away, barely 30 seconds into the movie, why I recommend it so dearly.

Let me give you a teaser by quoting Sinclair: “Have you ever wondered if a horse would let you ride her if there was no threat of punishment or encouragement of a reward such as food? Would a horse let you ride her simply because you had built a strong relationship?”

I wrote in my book Evolution (2014), “We humans can contemplate nothing without changing it. Yet, the most important, it seems to me, must be to understand, accept, and respect other living beings independently of species and race.”

That’s a normative statement, all right, and one you may beg to differ. I read, recently, a claim that respect being a human construct, does not exist for dogs. I’ll dispute vigorously that respect is a human construct. Sinclair’s movie is all about mutual respect between human and horse.

“We both have the right to live. I have the right to chase you, you have the right to fly,” the lion says to the gazelle. I suspect respect, as in acting as others have the same freedoms as we do, even though they may conflict with ours, is a fundamental law of nature. If so, this statement of mine, paradoxically enough, will cease to be normative and will become a premise for this universe’s sustainability.

That is something to ponder on.

Photo by Elsa Sinclair. Artwork by Anton Antonsen.

Featured Course of the Week

Ethology Ethology studies animal behavior in its natural environment. It is one of the fundamental courses in your curriculum. A reliable knowledge of animal behavior is the basis to create a satisfying relationship with any animal we train.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

Learn more in our course Ethology and Behaviorism. Based on Roger Abrantes’ book “Animal Training My Way—The Merging of Ethology and Behaviorism,” this online course explains and teaches you how to create a stable and balanced relationship with any animal. It analyses the way we interact with our animals, combines the best of ethology and behaviorism and comes up with an innovative, yet simple and efficient approach to animal training. A state-of-the-art online course in four lessons including videos, a beautiful flip-pages book, and quizzes.