Consciousness—Definitions

Do non-human animals have consciousness? Does this question belong to philosophy, ethology, neurobiology or physics?

Many philosophers distinguish between awareness and consciousness, awareness being a form of perception, and consciousness involving a special kind of self-awareness. Consciousness, in this view, requires a propositional awareness that it is I who am feeling or thinking. However, a dissociation between conscious and unconscious perception can occur in people with brain damage, who yet can make correct judgments even though they are not conscious of what they see.

The question of animal consciousness is indeed a difficult one. The spectrum of scientific opinion is vast. Some believe that consciousness does not occur in animals, and others maintain that most animals have consciousness. The difficulty of arriving at an acceptable and consensual definition of consciousness confounds the situation further.

To define consciousness in such a way that it only fits Homo sapiens sapiens seems to me too anthropocentric. To argue that if we have it, they can’t have it, is definitely committing the fallacy of anthropodimorphism, the opposite of anthropomorphism (Abrantes 2017).

Our tentative definition is: “Consciousness is the presence of mental images and their use by the organism to regulate its behavior. To be conscious is to be aware of what one is doing or plans to do. It is having a purpose and intention in one’s actions” (Abrantes 2012). This definition is quasi-identical to McFarland’s (1998).

Yet, we can imagine intentional behavior that does not involve consciousness. The standard examples of automatic, absent-minded activities, are walking and driving, where we solve relatively complex problems apparently without being conscious of (at least) some of the intentional states through which we must be passing.

“Another way to put the point is to note that intentionality alone is not sufficient for introspectibility, and so, insofar as introspectibility in the normal human case is a necessary condition for a state’s being conscious, intentionality is therefore also not sufficient for consciousness” (Rey 2008).

Another definition, proposed by Chandroo et al., is, ” Consciousness might be broadly described as an awareness of internal and external stimuli, having a sense of self and some understanding of ones place in the world” (Chandroo et al. 2004).

Damasio (2010) states that “[…] no one can prove satisfactorily that nonhuman, nonlanguage beings have consciousness, core or otherwise, although it is reasonable to triangulate the substantial evidence we have available and conclude that it is highly likely that they do.”

Private Experiences—Emotions

Emotion has subjective, physiological, and behavioral manifestations that are difficult to reconcile with each other. An emotion is a private experience. There is no way we can know the emotional experiences of another person. We tend to assume they are the same as ours, but we have no experimentally conclusive or logical way of verifying this.

In scientific terms, we cannot assume that animals have particular subjective feelings any more than we are entitled logically to make such assumptions about other people. In physiological terms, emotional states in humans are typically accompanied by autonomic changes, but these are not a reliable guide to identifying particular emotional states. Most animals, at least vertebrates, react to stressors in roughly the same way whether their emotional response is one of fear, of aggression or sexual nature.

Darwin (1872) postulated that facial expressions and other behavioral signs of emotion had evolved from protective responses and other utilitarian aspects of behavior. Darwin’s description was somehow anthropomorphic, which prompted psychologists to react. Lloyd Morgan (1882) advocated an approach devoid of speculation about the private thoughts and feelings of animals. The behaviorist attitude that the private mental experiences of animals cannot be the subject of scientific investigations dominated the first three-quarters of the 20th century.

The behaviorist position seems unassailable, but we can circumvent it in two ways. One argument (the logical one) is that although we cannot prove that animals have subjective experiences, it may be true nevertheless. No proof (yet discovered) does not conclusively imply non-existence. Another (the evolutionary probability argument) is to argue that it is unlikely, from an evolutionary stance, that there should be a marked discontinuity between humans and other animals in this respect. Therefore, if we accept the existence of subjective experiences in humans, then we are forced to admit that animals might have them as well.

Self-Awareness

Are animals aware of themselves in the sense that they know what posture they are adopting and what action they are taking? Sensory information from the joints and muscles is available to the brain, so it seems that animals should be aware of their behavior.

In an experiment, researchers trained rats to press one of four levers (Beninger et al. 1974). The rats learned to push a different bar, depending on whether they were grooming, walking, rearing up or remaining still when the buzzer sounded. In a sense, the rats must have been aware of their actions, which does not necessarily mean that they are conscious of them. They may be aware of their actions as they are aware of external stimuli.

The MSR (Mirror Self-Recognition) Test

Many animals respond to a mirror as if they saw another member of their species. Does that prove self-awareness? After many years of research, this remains a controversial question. There is evidence that chimpanzees and orangutans can recognize themselves in the mirror. Does the ability to respond to parts of one’s body seen in a mirror indicate self-awareness?

The questions are whether the MSR test is suitable for some species and whether it demonstrates self-awareness. Animals can be self-aware in ways the mirror test cannot measure, e.g., distinguishing between their own and others’ songs or scents (Bekoff 2002). Also, animals can pass the MSR, not necessarily having self-awareness (Cammaerts 2015). Very few species have passed the MSR test (Turner 2015).

The MSR test has limited value when we apply it to species that primarily use senses other than vision, as for example in dogs that mainly use olfaction and audition. Dogs do seem to discriminate their own odor from that of other dogs and to spend more time investigating their own modified odor ‘image,’ precisely as subjects who pass the MSR test do (Horowitz 2017).

A capacity for self-recognition in a mirror does not necessarily imply an awareness of one’s own psychological states and the understanding that others possess such states (Povinelli, 1998).

Imitation

Does the ability to imitate the actions of others indicate self-awareness? Imitations do not demonstrate the implication of mental states because of the extensive training involved in the experiments.

We take the ability to imitate as a sign of intelligence. Parrots, Psittaciformes, and mynah birds, Sturnidae, can reproduce human sounds with extraordinary fidelity. Are they particularly intelligent?

To be able to imitate, an animal must perceive the external auditory or visual example and match it with a set of motor instructions of its own. For example, a baby who imitates an adult waving must somehow associate the sight of the hand with his own motor instructions for waving. The baby does not need to be aware that he has a hand, it merely has to connect a particular perception with a specific set of motor commands. How that is done, it is a mystery, but the question of whether imitation necessarily involves self-awareness is debatable.

Even though deliberately copying behavior would be a strong argument for self-awareness, we cannot be sure all apparently imitative behavior is.

Allelommetic behavior (synchronous behavior, mimetic behavior, imitative behavior, and social facilitation) may have evolved because a specific synchronization was advantageous. Sometimes, environmental cues initiate this behavioral synchrony (seen in dogs, horses, sheep, chicken, etc.) (Miller 1996, Stoye, S. et al. 2012).

Humans often find themselves assuming similar postures without being aware of that (not conscious of that). It may be the result of empathy, which may also have developed in some species because of the conferred benefits.

Does the brain potential associated with movement occur before or after we are aware of our movement intention? Do I think, “I’m going to move my finger” and then do it? Or does it happen the other way round: I move my finger, and then I’m aware of that? Does consciousness have a causal influence on movement decision? (Guggisberg et al. 2013).

Awareness of Others—Empathy

Empathy means some awareness of others as beings with feelings similar to our own. Some researchers argue that the evolution of close-knit societies made recognition of others, i.e., empathy, advantageous. Empathic behavior is subject to evolutionary laws as any other behavior.

Bischoff-Köhler (1990) investigated the onset of empathy in infants. The results showed that between 16 and 24 months of age, there was a transition from non-recognition to mirror recognition and a simultaneous transition from non-empathy to empathy. Moreover, these transitions occurred at the same age in a given child.

The nature of the phenomenon of empathy in animals is also a topic of investigation (Preston & de Waal 2002). Mice that observe a cagemate in pain are more sensitive to painful stimuli than mice that see an unfamiliar mouse similarly treated (Langford et al. 2006). Empathy can also be the best explanation for some elephant behavior (Byrne et al. 2008).

Finally, empathy does not need to be an all-or-nothing phenomenon (DeWall 1996). Neither does consciousness. As there are various degrees of empathy, there are possibly different levels of consciousness.

The concrete encounter of self and other fundamentally involves empathy, as a unique and irreducible kind of intentionality. Thus, empathy seems to be a precondition for consciousness (Thompson 2001).

However, self-awareness (consciousness) does not always require empathy. That means we can conclude that animals showing empathy must be self-aware. However, we cannot conclude that those who lack manifestations of empathy do not possess self-awareness.

Pain—Do Animals Have to be Conscious in Order to Suffer?

It is difficult to define and analyze pain as the interpretation of findings rest primarily on the behavioral criterion we use. A pure withdrawal reflex would probably not be a good indication of pain. Such reflexes are widespread in the animal kingdom, occur in very primitive animals, and are not always associated with any strong aversive.

The criterion of crying out in pain is not good either. While a dog or a monkey scream in pain when they are seriously injured (or even less seriously), an antelope torn to pieces by a predator remains relatively silent.

Do animals have to be conscious in order to suffer? When we are unconscious, we do not suffer pain or mental anguish because parts of our brain are deactivated. However, we do not know whether these parts are involved only in consciousness or also in other aspects of brain activity. Thus, we cannot say that because we do not experience pain when we are unconscious means that consciousness and suffering are intrinsically related. Perhaps whatever makes us unconscious also stops the pain, but the two are not causally connected.

The truth is that we have no conception of what the conscious experiences of animals might involve if they exist because we have no precise understanding of what consciousness is. Therefore, we can draw no conclusions about the relationship between consciousness and suffering in animals.

Amidst our ignorance, it would be wrong to assume that suffering in animals is confined to those that are intelligent, that use language or that show evidence of conscious experience.

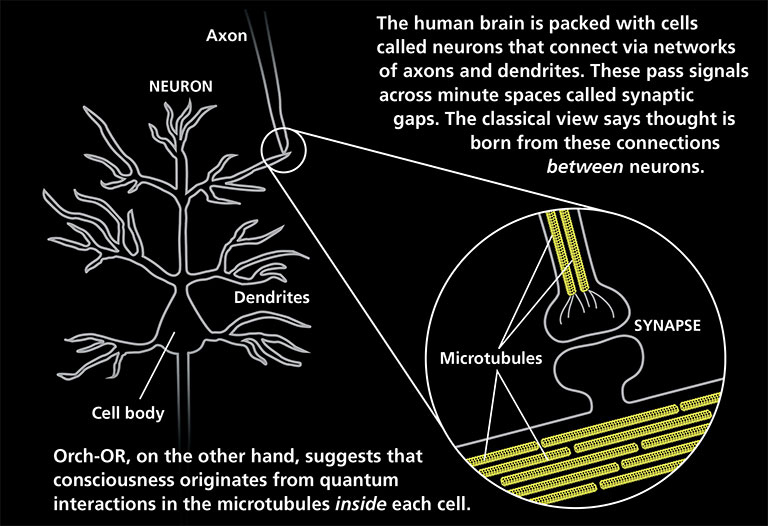

Orch-OR is fully compatible with the view that non-human animals possess consciousness to some degree or another. In fact, the opposite would be absurd (illustration from “Consciousness in the Universe: A Review of the ‘Orch OR’ Theory.” Physics of Life Reviews, 2014).

Consciousness as a Quantum State—Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch OR)

The Orch-OR model, based on quantum physics, suggests that consciousness originates from microtubules and actions inside neurons (Hameroff 1988, Hameroff and Penrose 2016).

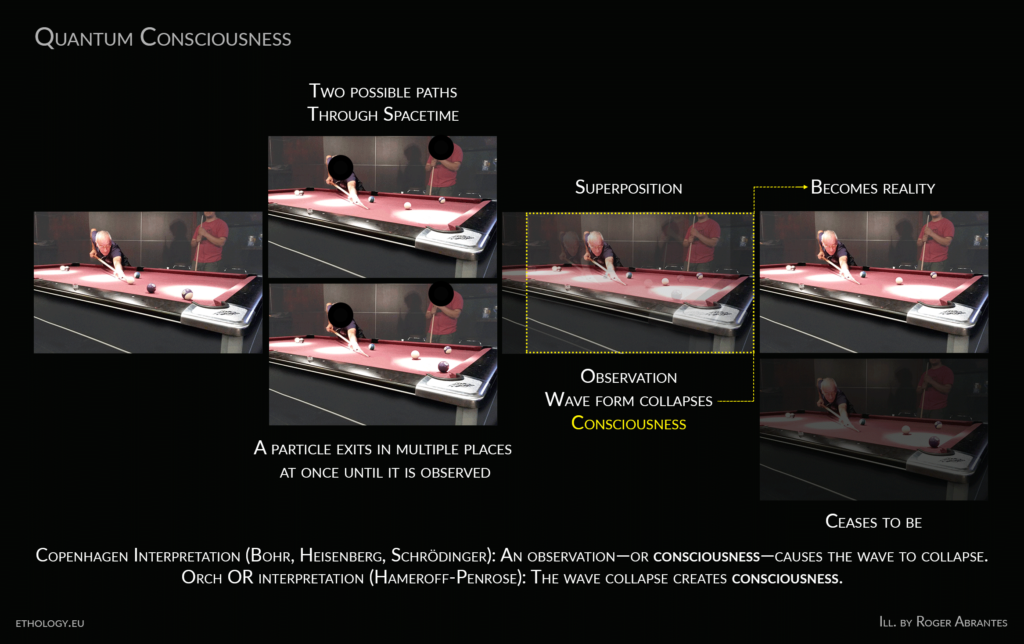

Classic and quantum physics differ in their accounting of events. When I hit a pool ball, I use traditional physics (and geometry) to predict where it will be at any particular moment. I expect it to do so (assuming I hit it correctly). However, in quantum physics, such expectation is null and void. According to the (Copenhagen) interpretation of quantum mechanics, any movement is unknown until it is observed. That is not as weird as it might seem. Imagine, I close my eyes just before I hit the cue ball. While my eyes remain shut, the object ball is both pocketed and non-pocketed. It is first when I open them, that the ball is definitely in one place. Physicists refer to this observation, which determines what happened, as a wave collapsing into a single state.

In quantum systems, inside the neuron, Hameroff and Penrose argue that it is every single collapse of the wave function that returns a conscious moment. Their model met some criticism. Most scientists believe the brain is too warm and wet for quantum states to have any influence on neuronal activity because quantum coherence only seems possible in fairly shielded and cold environments. Biological processes, in general, seem too messy for quantum physics o thrive.

However, researchers have recently found that quantum effects are indeed significant for particular biological processes, like photosynthesis (Engel 2007, Brookes 2017). When a photon hits an electron in a leaf, the electron delivers it to another molecule (the reaction center), which converts light into chemical energy (and feeds the plant). The electron uses the quantum effect of superposition, where a particle can be in two places at once while testing various routes to the reaction center where the photosynthesis occurs. Then, it takes the most efficient one. Besides photosynthesis, olfaction may also be a product of quantum processes (Brookes 2017).

Another support for the idea that quantum physics are indeed possible in the inhospitable organic environment of the brain is via the Phosphorus molecule. The central idea is that the Phosphorous molecule in the brain with its nuclear spin can potentially act as a qubit (quantum bit) and promote quantum computation. This hypothesis circumvents the problem of quantum decoherence by proposing that the qubits remain stable, in spite of the higher temperature of the brain, by organizing themselves into a Phosphate ring (Fisher 2015).

The microtubules, essential in the Orch-OR model, may very well be the first cause of thought. The traditional view is that neurons fire when a channel within the cell membrane opens, flooding the neuron with positively charged ions. Once a determined threshold is reached, an electrical signal travels down the axon—the nerve fibers within the neuron—and the neuron fires. Axons connect neurons to other cells, and inside each axon are nanowires, including the microtubule. Bandyopadhyay found that he could apply a charge to the microtubule, causing activity to raise in the neuron. The nanowires fire thousands of times faster than the average activity in a neuron. The neuron, opposite prevailing scientific knowledge, wasn’t the first cause of the human thought process (Bandyopadhyay 2014).

According to the Penrose–Hameroff model, consciousness results from discrete physical events; such events have always existed in the universe as non-cognitive, proto-conscious events. Biology evolved a mechanism to orchestrate such events and to pair them to neuronal activity, resulting in meaningful, cognitive, conscious moments of quantum state reduction. In the Orch OR theory, these conscious events are terminations of quantum computations in brain microtubules reduced by objective reduction (OR), and having experiential qualities. In this view, consciousness is an intrinsic feature of the action of the universe (Hameroff 1998, Hameroff & Penrose 2016).

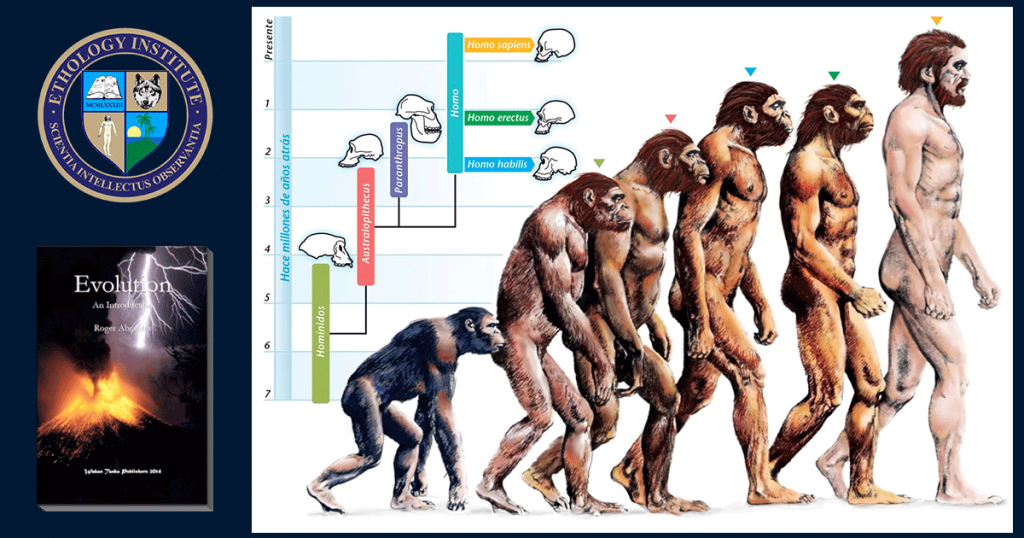

Darwin’s theory of natural selection suggests that life evolved by natural selection in incremental steps and random mutations. Therefore, we would not expect the substantial level of coherence across the brain that would be necessary for the non-computable Orch OR of conscious human understanding to appear any other way. More primitive (less elaborated) forms must have preceded it, shown variation, and been subject to natural selection. Thus, proto-conscious Orch OR states might have emerged step by step in the course of evolution.

Orch-OR is fully compatible with the view that non-human animals possess consciousness to some degree or another. In fact, the opposite would be absurd.

When I hit the cue ball, I use traditional physics (and geometry) to predict where it will be at any particular moment. I expect it to do so (assuming I hit it correctly). However, according to the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, any movement is unknown until it is observed. Imagine, I close my eyes just before I hit the cue ball. While my eyes (and my opponent’s, Michael McManus, in this case) remain shut, the object ball is pocketed and non-pocketed at once. It is first when we open our eyes, that the object ball is definitely pocketed.

The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness

Publicly proclaimed in Cambridge, UK, on July 7, 2012, at the Francis Crick Memorial Conference on Consciousness in Human and non-Human Animals, reads:

“The absence of a neocortex does not appear to preclude an organism from experiencing affective states. Convergent evidence indicates that non-human animals have the neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and neurophysiological substrates of conscious states along with the capacity to exhibit intentional behaviors. Consequently, the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Non-human animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates” (Low, Philip, et al. 2012).

The essential point in this declaration is that concurrent studies concluded that human and some non-human animals share the neurological substrates that we consider indispensable to generate consciousness. That may indeed be helpful in our quest for non-animal consciousness.

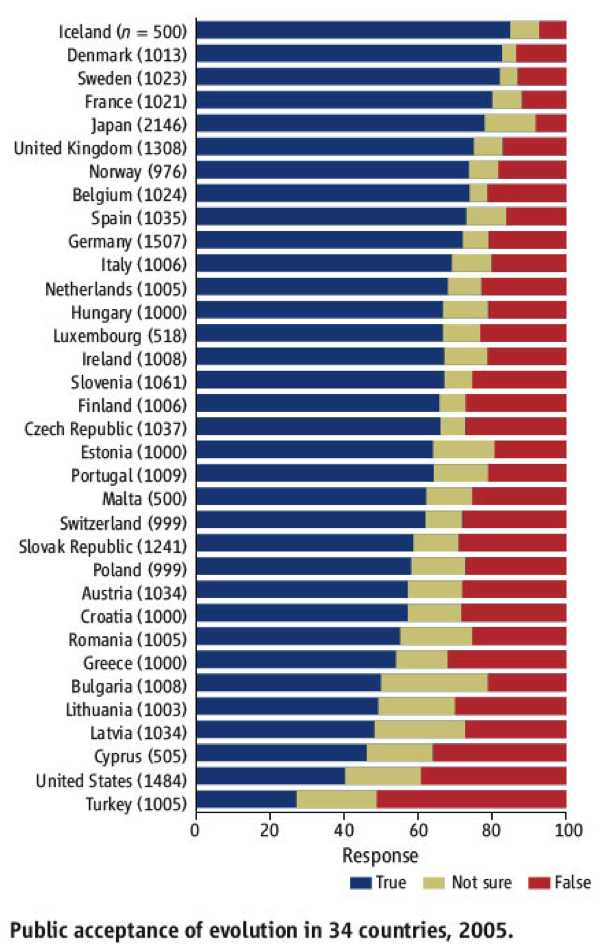

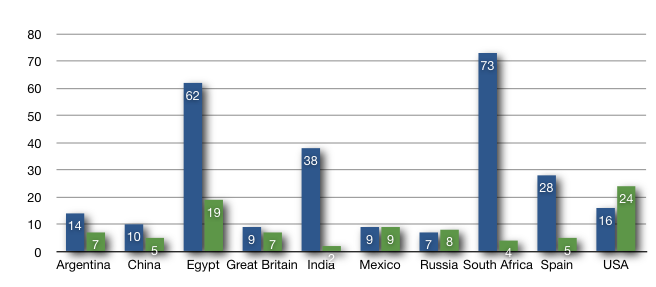

Otherwise, the document (as other similar ones) is more a political statement than scientific proof. The fact that it is signed by many (argumentum ad populum) prominent (argumentum ad verecundiam) persons does not add anything to the truth or falsity of its statement about consciousness (Copi 2014). Were the opinion of many the truth, the earth would be flat, after having been created in seven days (Genesis 1 and 2). Were the opinion of prominent persons the truth, DNA would have three intertwined strands (Linus Pauling), and life could originate from inanimate matter (Aristotle); and the Spiroptera carcinoma would (falsely) cause cancer (for which, in 1926, Johannes Fibiger won the Nobel Prize in Medicine).

Final Note

Human consciousness is by definition subjective and private. We access it through verbal, non-verbal, and instrumental records. Animals do not have language (as we define it), but we can still study their consciousness via behavioral investigations, as we do in preverbal infants. Like humans, animals display different behaviors depending on levels of consciousness. During sleep or anesthesia, no individual—unconscious or having low levels of consciousness—independently of species, can process information (not the full range, at least). On the other hand, behavioral and neurobiological data lead us to the conclusion that animals can express some forms of what we call a higher level of consciousness.

The subject of non-human animal consciousness is relevant to many topics, e.g., ethics and theory of mind. Some scientists and philosophers believe that the foundations have been set for addressing (at least) some of the questions about animal consciousness in an empirically way. Some remain skeptical, maintaining that subjective phenomena are beyond the reach of scientific research. The arguments on both sides are many, and the jury is still out.

Conclusion

As a sort of conclusion, it is the view of this author that we have two main unsolved problems related to consciousness: (1) to formulate a conclusive and clear operational definition, and (2) to devise a valid verification method for single species.

As such, at this moment, the most prudent statement seems to be that animals (humans included) show varying degrees of consciousness depending on species. It appears beyond any reasonable doubt that some have it and, therefore, (1) if some have it, others (high) probably have it, too, albeit differently—and (2) that some have it, doesn’t necessarily imply all have it—unless, of course, Hameroff and Penrose are right.

Thank you to John Larsen and Parichart Thongparkdee Abrantes for the exciting exchange of ideas we have had while I wrote this paper.

References

Abrantes, R. 2012. Ethology—The Study of Animal behavior in the Natural Environment. Wakan Tanka Pub. Online flipping-page book.

Abrantes, R. 2017. Do Animals Have Feelings? Ethology Institute Website.

Bandyopadhyay, A. 2014. Evidence of massive global synchronization and the consciousness. Physics of Life Reviews.

Bekoff, M. (2002). Animal reflections. Nature. 419 (6904): 255. doi:10.1038/419255a.

Bekoff, M. and Sherman, P.W. 2004.Reflections on animal selves. TRENDS in Ecology and Evolution Vol.19 No.4 April 2004.

Beninger et al. 1974. The ability of rats to discriminate their own behaviours. Canadian Journal of Psychology (Revue Canadienne de Psychologie) 28(1):79-91 DOI: 10.1037/h0081979

Bischof-Köhler, D. (2012). Empathy and Self-Recognition in Phylogenetic and Ontogenetic Perspective. Emotion Review, 4(1), 40–48.

Brown 2015. Brown, C., 2015. Fish intelligence, sentience and ethics. Animal Cognition, 18(1): 1-17.

Brookes, J.C. 2017. Quantum effects in biology: golden rule in enzymes, olfaction, photosynthesis and magnetodetection. Proc Math Phys Eng Sci. 2017 May; 473(2201): 20160822. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2016.0822.

Byrne, R. W., et al. (2008). Do Elephants Show Empathy? Journal of Consciousness Studies, 15(10–11), 204–225.

Cammaerts, M-C, and Cammaerts, R. 2015. Are ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) capable of self recognition? (PDF). Journal of Science. 5(7): 521–532.

Chandroo et al. 2004 Chandroo, K.P.; Yue, S.; Moccia, R.D. 2004. An evaluation of current perspectives on consciousness and pain in fishes. Fish and Fisheries, 5(4): 281-295.

Clayton, D.A. 1978. Socially facilitated behavior. Quarterly Review of Biology, 53: 373-392.

Collin, A. and Trestman, M. 2017. Animal Consciousness. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.),

Copi, I. 2014. Introduction to Logic. Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 10: 1-292-02482-8.

Damasio, A.R. 2010. Self comes to mind: constructing the conscious brain (PDF). New York: Pantheon Books, 2010. ISBN-10: 150124695X

Darwin, C. 1859. On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or The preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. London: J. Murray.

Darwin, C. 1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. London; Princeton, NJ: J. Murray ; Princeton University Press, 1981.

Darwin, C. 1872. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London; Oxford: J. Murray ; Oxford University Press, 1998.

Dawkins, M.S., 1998. Through our eyes only? The search for animal consciousness. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN-10: 0198503202

Dawkins, M. S. 2012. Animal Suffering: The Science of Animal Welfare. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9400959052, 9789400959057.

Dennett, D. C. (1969). Content and Consciousness—An Analysis of Mental Phenomena. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN: 9780710065124

Dennett, D.C. 1991. Consciousness Explained (PDF). New York: Back Bay Books/Little, Brown and Company, 1991. 511 p.

Dennett, D.C. 1995. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea—Evolution and the Meanings of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN: 0-684-80290-2. http://www.inf.fu-berlin.de/lehre/pmo/eng/Dennett-Darwin%27sDangerousIdea.pdf.

Engel, G.S. et al. 2007. Evidence for wavelike energy transfer through quantum coherence in photosynthetic systems. Nature volume 446, pages 782–786 (12 April 2007).

Fisher, M. P.A. 2015. Quantum cognition: The possibility of processing with nuclear spins in the brain. Annals of Physics 362 (2015) 593–602.

Gallego, M.B. 2011. The bohm-penrose-hameroff model for consciousness and free will theoretical foundations and empirical evidences. Pensamiento 67 (254):661-674

Gallup, G. G. Jr. 1970. Chimpanzees: Self-Recognition (PDF). Science, 167 (3914), 86-87.

Gallup, G. G. Jr. 1982. Self‐awareness and the emergence of mind in primates. American Journal of Primatology, 2(3), 237–248.

Guggisberg et al. 2013. Timing and awareness of movement decisions: does consciousness really come too late? Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:385.

Hameroff, S.R. 1998. Quantum computation in brain microtubules? The Penrose–Hameroff ‘Orch OR’ model of consciousness. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A (1998) 356, 1869–1896

Hameroff, S.R. and Penrose, R. 2016. Consciousness in the Universe: An Updated Review of the “ORCH OR” Theory. In Biophysics of Consciousness: A Foundational Approach by R. R. Poznanski, J. A. Tuszynski and T. E. Feinberg. World Scientific, Singapore. (pp 520-630).

Horowitz, A. 2017. Smelling themselves: Dogs investigate their own odours longer when modified in an “olfactory mirror” test. Behavioural Processes. 143C: 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2017.08.001. PMID 28797909.

Hume, D. 1888. A Treatise of Human Nature, edited by L.A. Selby-Bigge (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780198245889.

Huxley, T. H. 1874. On the hypothesis that animals are automata, and its history. Fortnightly Review, 95, 555-580.

James, W. 1879. Are we automata? Mind, 4, 1–22. Online.

Langford, D. et al. 2006. Social Modulation of Pain as Evidence for Empathy in Mice. Science 312(5782):1967-70. DOI: 10.1126/science.1128322.

Libet B., Gleason C. A., Wright E. W., Pearl D. K. 1983. Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain 106, 623–642 10.

Low, Philip et al. 2012. The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness Publicly proclaimed in Cambridge, UK, on July 7, 2012, at the Francis Crick Memorial Conference on Consciousness in Human and non-Human Animals.

Nagel, T. 1979. Mortal questions. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press (1613). ASIN: B074RB5VTD.

Neindre, P. et al. 2017. Animal consciousness. European Food Safety Authority. 2017, 165 p.

McFarland, D. 1998. Animal Behaviour: Psychobiology, Ethology and Evolution. Benjamin Cummings; 3 ed. ISBN-10: 0582327326.

Morgan, C. L. 1882. Animal intelligence. Nature, 26, 523-524.

Miller, R.M. 1996. Allelomimetic behavior. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 16(7): 282–284.

Povinelli, D.J. 1998. Can animals empathize? Maybe not. Scientific American, pp. 67–75.

Preston, S. and de Waal F.B.M. 2002. Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav. and Brain Science (2002) 25, 1–72.

Rey, G. 2008. Even Higher-Order) Intentionality Without Consciousness. Revue internationale de philosophie 2008/1 (n° 243), pages 51 à 78.

Stoye, S. et al. 2012. Synchronized lying in cattle in relation to time of day. Livestock Science. 149(1–2): 70–73.

Thompson, E. 2001. Empathy and Consciousness(PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8, No. 5–7, 2001, pp. 1–32

Turner, R. 2015, 10 Animals with Self Awareness. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

de Waal, F. (1996), Good Natured: The Origins of Right and Wrong in Humans and Other Animals. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Zahavi, D. (2011). Empathy and direct social perception. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 3, 541–558.

Featured Course of the Week

Agonistic Behavior Agonistic Behavior is all forms of aggression, threat, fear, pacifying behavior, fight or flight, arising from confrontations between individuals of the same species. This course gives you the scientific definitions and facts.

Featured Price: € 168.00 € 98.00

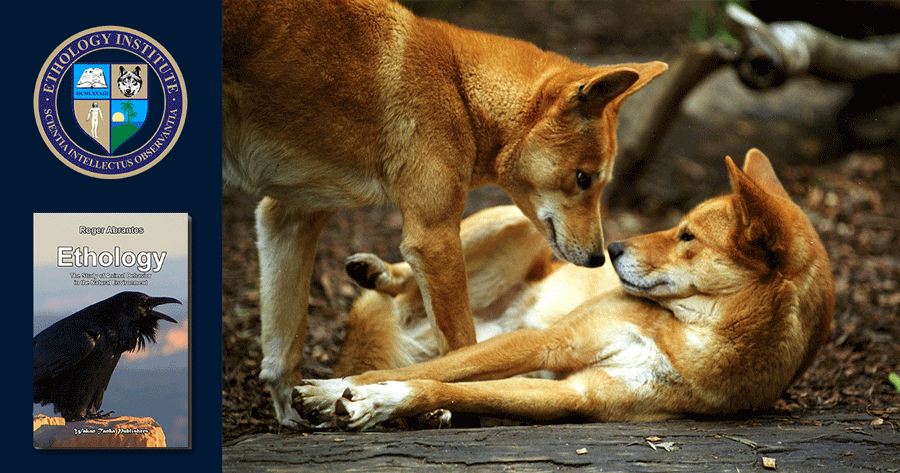

Learn more in our course Ethology. Ethology studies the behavior of animals in their natural environment. It is fundamental knowledge for the dedicated student of animal behavior as well as for any competent animal trainer. Roger Abrantes wrote the textbook included in the online course as a beautiful flip page book. Learn ethology from a leading ethologist.